Blog

2025-03-17

This is an article which I wrote for

Chalkdust issue 21.

For ten years now, I've been setting the Chalkdust crossnumber. Over this time, I've developed a lot of tricks and tools for setting good puzzles.

Although puzzles involving words in grids of squares have been around since at least the 1800s, the first crossword (or word-cross as the author called it) puzzle was published in the New York World newspaper in 1913. Since this, crosswords have become a staple in newspapers and magazines around the world.

In the UK, cryptic crosswords were invented and grew in popularity in the 1900s and now appear in most newspapers and magazines. The cryptic crossword in the Listener magazine became infamous as the hardest such puzzle. the Listener ceased publication in 1991, but the Listener crossword still lives on and is now published on Saturdays in the Times newspaper.

In early 2015, we were discussing ideas for regular content in our brand new maths magazine, and wanted to include a more mathematical crossword-style puzzle. Like Venus emerging from the shell, the crossnumber was born.

Of course, we didn't invent the crossnumber puzzle: the first known crossnumber puzzle was written by Henry Dudeney and published by Strand Magazine in 1926; four times a year, the Listener features a numerical puzzle; and the UKMT (United Kingdom Mathematics Trust) have included a crossnumber as part of their team challenge for many years. There are also plenty of other publications that include crossnumbers, including the very enjoyable Crossnumbers Quarterly, that's been publishing collections of the puzzles four times a year since 2016. But perhaps we'll be mentioned in a footnote in a book about the history of puzzles.

But anyway, we'd decided we needed a crossnumber, so I needed to write one...

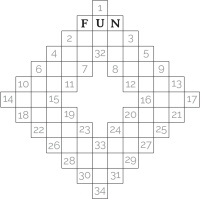

Making a grid

The first step when creating a puzzle is to create the grid. Like many publications, we restrict ourselves to using grids of squares (for the main crossnumber at least---we allow more freedom in other puzzles that we feature).

Typically, a publication will impose some restrictions on the placement of the black squares in its puzzle. The most popular restrictions are:

- The white squares must be simply connected (for any two white squares, it is possible to draw a path between them that only goes through white squares);

- The arrangement of black squares must be in some way symmetric;

- The proportion of squares that are black cannot be too high.

There are two forms of symmetry that are used in crossword grids: rotational symmetry and reflectional symmetry. Both order 2 (rotate the grid 180° and it looks the same) and order 4 (rotate the grid 90° and it looks the same) rotational symmetry are commonly used in crossword grids, with order 2 rotational symmetry often being the minimal allowable amount of symmetry. You'll want to be careful when making a grid with order 4 rotational symmetry, as it's very easy to make your grid into an accidental swastika.

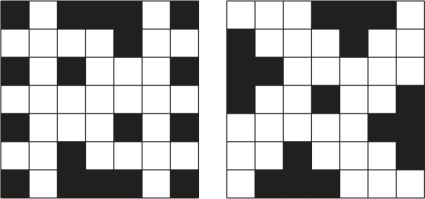

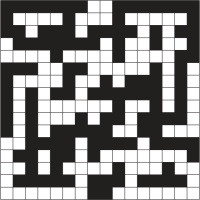

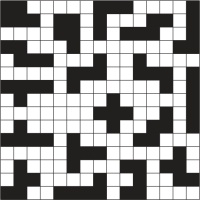

With a few notable exceptions, the grids for the Chalkdust crossnumber have some form of symmetry, and also follow the other two restrictions. We do, however, allow some flexibility on these restrictions if it allows us to use an interesting grid. For crossnumber #14 (shown on the left), we experimented with translational symmetry, leading to a grid that was not simply connected and with a greater than usual proportion of black squares. For crossnumbers #11 and #6, the grids had a nice property: rotating the grid leads to the same pattern of squares with the colours inverted. Once again we had to break the requirements on connectedness and the proportion of black squares to do this.

The grid for crossnumber #11. Rotating this grid 90° leads to the same grid with inverted colours. This grid also has order 2 rotational symmetry.

The grid for crossnumber #6. Rotating this grid 180° leads to the same grid with inverted colours.

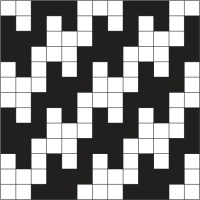

The grid for crossnumber #17 was not symmetric, and instead included all 18 pentominoes in black.

For crossnumber #17, we skipped imposing symmetry entirely and instead formed all 18 pentominoes from the black squares in the grid. This really pleased me, as there were clues in the puzzle related to the number of pentominoes and the number of black squares in the grid.

For American style crosswords, there's an additional restriction that is imposed: all white squares must be checked. A white square is called 'checked' if it is part of an across entry and a down entry---and so you can fill that square in by solving one of two different clues. Due to this, American crosswords will have large rectangles composed entirely of white squares and never have lines of alternating black and white squares as commonly seen in British puzzles.

When writing a crossword, it is common to pick the words to include while making the grid, as trying to find valid words or phrases to fill a predetermined grid is a challenging task. (Thankfully, there's software out there that can help you make grids from a list of words.) For crossnumbers, filling the grid is a much easier task as any string of digits not starting with a zero is a valid entry. This ease of filling the grid is what allowed us to use the interesting restriction-breaking grids mentioned in this section.

For crosswords, it is also common to disallow the use of two-letter words. For the crossnumber, removing two-digit numbers would remove the potential for a lot of fun number puzzles, so we don't impose this restriction here. We allow two-letter words in the Chalkdust cryptic too, as they can be really useful when trying to make a grid with our additional restriction that the majority of the included words should be related to maths.

Setting the clues

Once I've made the grid for a crossnumber, the next task is to write the clues.

Often, I start this task by picking a fun mathematical or logic puzzle to include in the clues. Sometimes, this is a single clue, such as this one from crossnumber #1:

Down

6. This number's first digit tells you how many 0s are in this number, the second digit how many 1s, the third digit how many 2s, and so on. (10)

Or this clue from crossnumber #5:

Across

9. A number \(a\) such that the equation \(3x^2+ax+75\) has a repeated root. (2)

Other times, this could be a set of clues that refer to each other and reveal enough information to work out what one of the entries should be, such as these clues from crossnumber #10:

Across

13. 49A reversed. (3)

37. The difference between 49A and 13A. (3)

47. 37A reversed. (3)

48. The sum of 47A and 37A. (4)

49. Each digit of this number (except the first) is (strictly) less than the previous digit. (3)

Once I've included a few sets of clues like this, it's time to write the rest of the clues. As any crossnumber solvers will have noticed, my favourite type of clue to add from this point on is a clue that refers to another entry.

More recently, I've begun adding an additional mechanic to each crossnumber. This started in crossnumber #13, when all the clues involved two conditions which were joined by an and, or, xor, nand, nor or xnor connective. Mechanics in later puzzles have included the clues being given in a random order without clue numbers (#14), some clues being false (#16), and each clue being satisfied by both the entry and the entry reversed (#19). I really hope that you enjoy the 'fun' mechanic I used in this issue's puzzle.

Around the same time as I started playing with additional mechanics, my taste in puzzles shifted. Older crossnumbers had been quite computational, and often needed some programming for a few of the clues, but more recently I have become a greater fan of logic puzzles and number puzzles that can be solved by hand. To reflect the change in the type of puzzle I was setting we added the phrase 'but no programming should be necessary to solve the puzzle' to the instructions, starting with crossnumber #14.

Thinking like a mega-pedant

One of the most important things to watch out from when writing and checking clues is accidental ambiguity due to writing maths in words.

For example, the clue 'A factor of 6 more than 2D' could be read in two ways: this could be asking the solver to add 6 to 2D, then find a factor of the result; or it could be asking the solver to add 1, 2, 3, or 6 (ie a factor of 6) to 2D.

As long as I spot clues like this, it can usually be fixed with some rewording. In this example, I'd rewrite the clues as either '2D plus a factor of 6.' or 'This number is a factor of the sum of 6 and 2D.'

In my time setting the crossnumber, I've got a lot better at spotting ambiguity in clues, and do this by reading through the clues and trying to be a mega-pedant and intentionally misinterpret them. It can be really helpful to get someone else to help with this check though, as remembering what you intended to mean when writing a clue can make it hard to read them critically.

Checking uniqueness

Perhaps the most difficult part of setting a crossnumber is checking that there is exactly one solution to the completed puzzle.

To help with this task, I've written a load of Python code to help me find all the solutions to the puzzle. I run this a lot while writing clues to make sure there's no area of the puzzle where I've left multiple options for a digit. I intentionally use a lot of brute force in this code so that it's really good at catching situations where there are multiple answers to a puzzle where I only found one solution by hand.

Once I've got all the clues and my code says the solution is unique, I do a full solve of the puzzle by hand. This is both to confirm that the code's conclusion was not due to a bug, and to check that the difficulty of the puzzle is reasonable.

Following this checking, and a little proofreading, the puzzle is ready for publishing. Then the fun part begins, as I get to chill with a nice cup of tea and wait for people to submit their answers.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment

2025-01-26

Welcome to 2025 everyone! It's time to reveal the answers to the Advent Calendar puzzles and announce the winners.

But first, some good news: with your help, Santa was able to open the warehouse to get the presents and Christmas was saved!

Now that the competition is over, the questions and all the answers can be found at mscroggs.co.uk/puzzles/advent2024.

Before announcing the winners, I'm going to go through some of my favourite puzzles from the calendar and a couple of other interesting bits and pieces.

Highlights

My first highlight is the puzzle from 2 December. I like this puzzle, because at first it looks really difficult, as there are so many different combinations that could

be rolles with 100 dice. But after some thought, it turns out that the answer isn't any different to if there were only 2 dice.

2 December

14 is the smallest even number that cannot be obtained by rolling two 6-sided dice and finding

the product of the numbers rolled.

What is the smallest even number that cannot be obtained by rolling one hundred 100-sided dice

and finding the product of the numbers rolled?

My next highlight is the puzzle on 6 December, as it can be solved by spotting a really satisfying pattern.

6 December

The number n has 55 digits. All of its digits are 9.

What is the sum of the digits of n3?

My final highlight is the puzzle from 23 December. I like this puzzle so much that I've written a whole blog post about it, and am in the middle of writing a second blog post

about it.

23 December

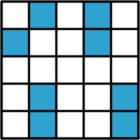

In a grid of squares, each square is friendly with itself and friendly with every square that is horizontally, vertically, or diagonally adjacent to it (and is not friendly with any other squares).

In a 5×5 grid, it is possible to colour 8 squares so that every square is friendly with at least two coloured squares:

It it not possible to do this by colouring fewer than 8 squares.

What is the fewest number of squares that need to be coloured in a

23×23 grid so that every square is friendly with at least two coloured squares?

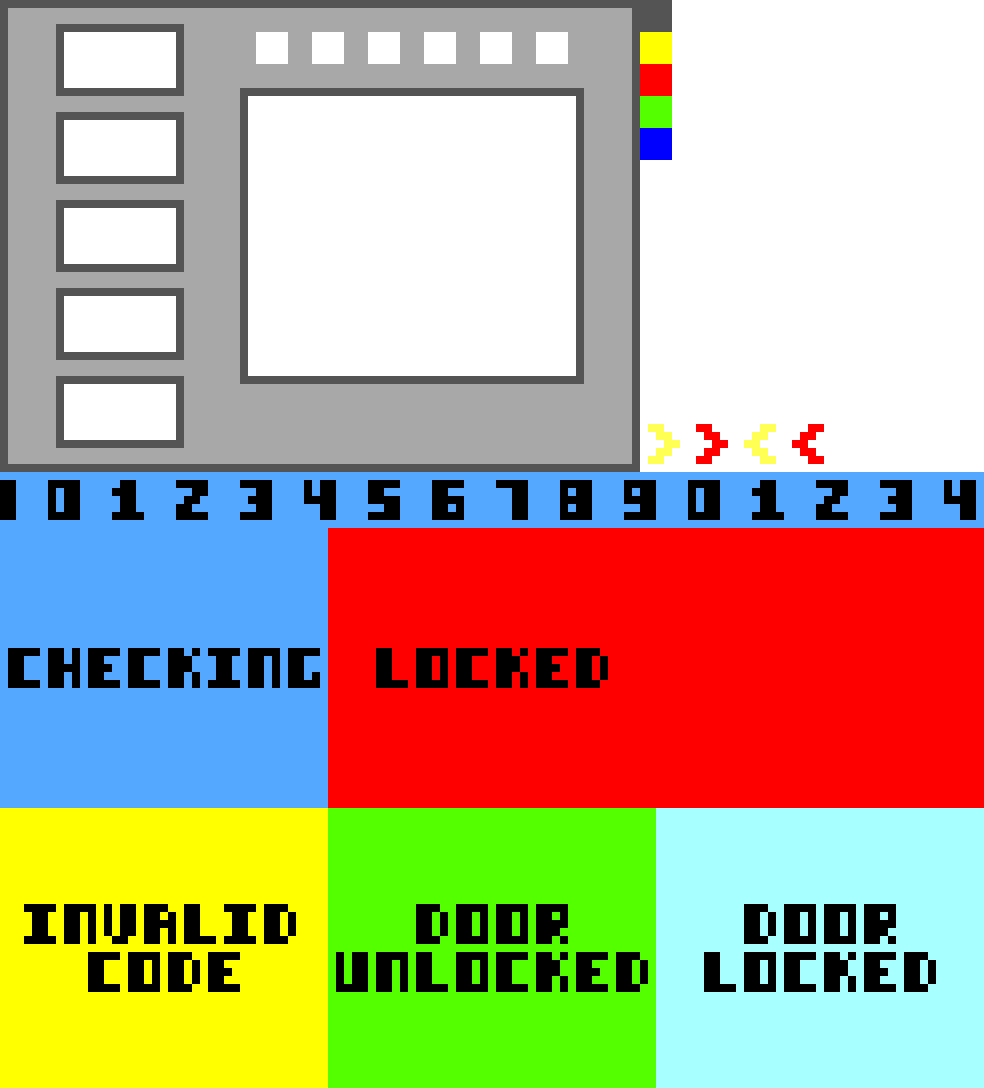

Hardest and easiest puzzles

Once you've entered 24 answers, the calendar checks these and tells you how many are correct. I logged the answers that were sent

for checking and have looked at these to see which puzzles were the most and least commonly incorrect. The bar chart below shows the total number

of incorrect attempts at each question.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| Day | |||||||||||||||||||||||

It looks like the hardest puzzles were on

23 and

8 December;

and the easiest puzzles were on

1 and

15 December.

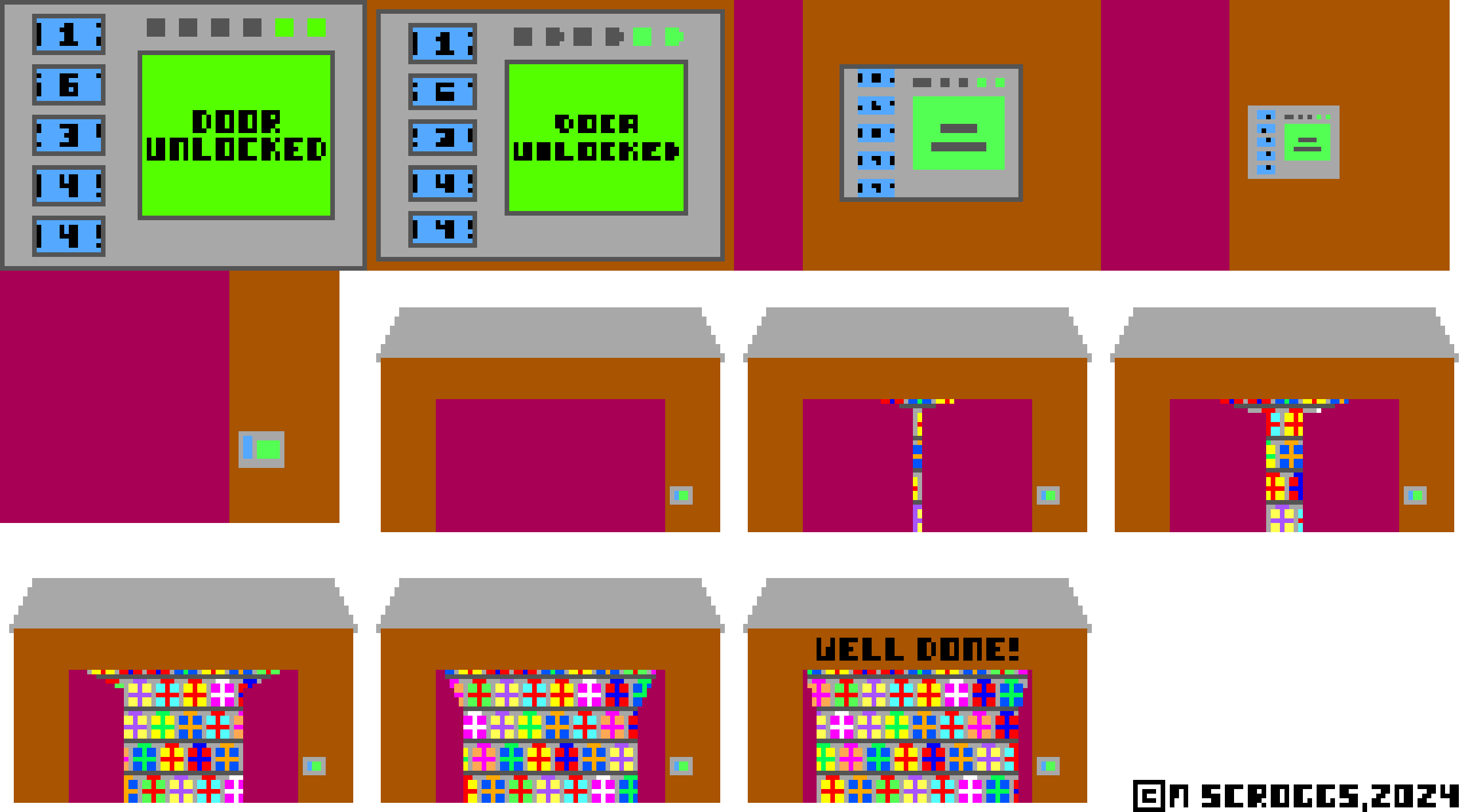

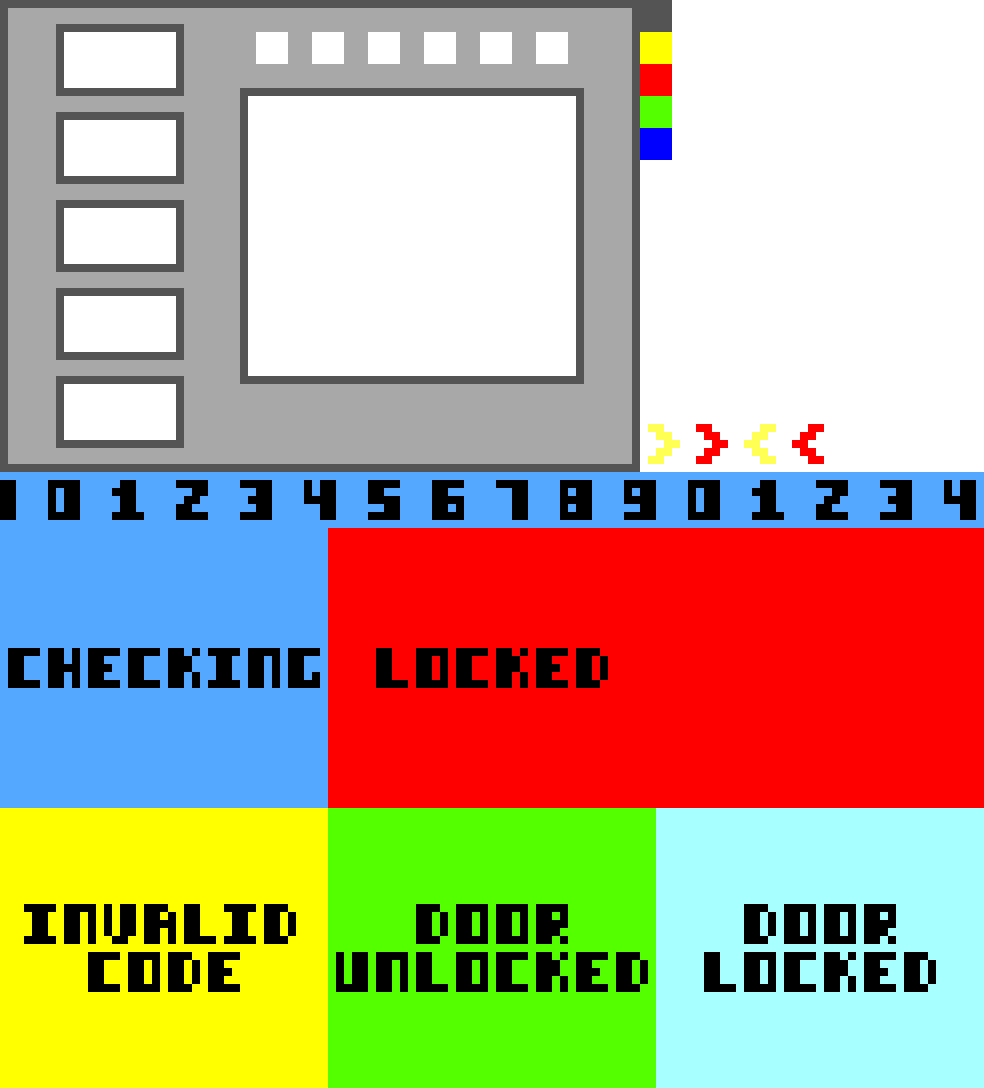

Opening the warehouse

To finish the Advent calendar, you were tasked with opening the warehouse full of presents. The answers to all the puzzles were required to

be certain of which combination of parts were needed to open the warehouse, but it was possible to reduce the number of options

to a small number and get lucky when trying these options. This year only one person got lucky warly.

This graph shows how many people opened the warehouse on each day:

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| Day | ||||||||||

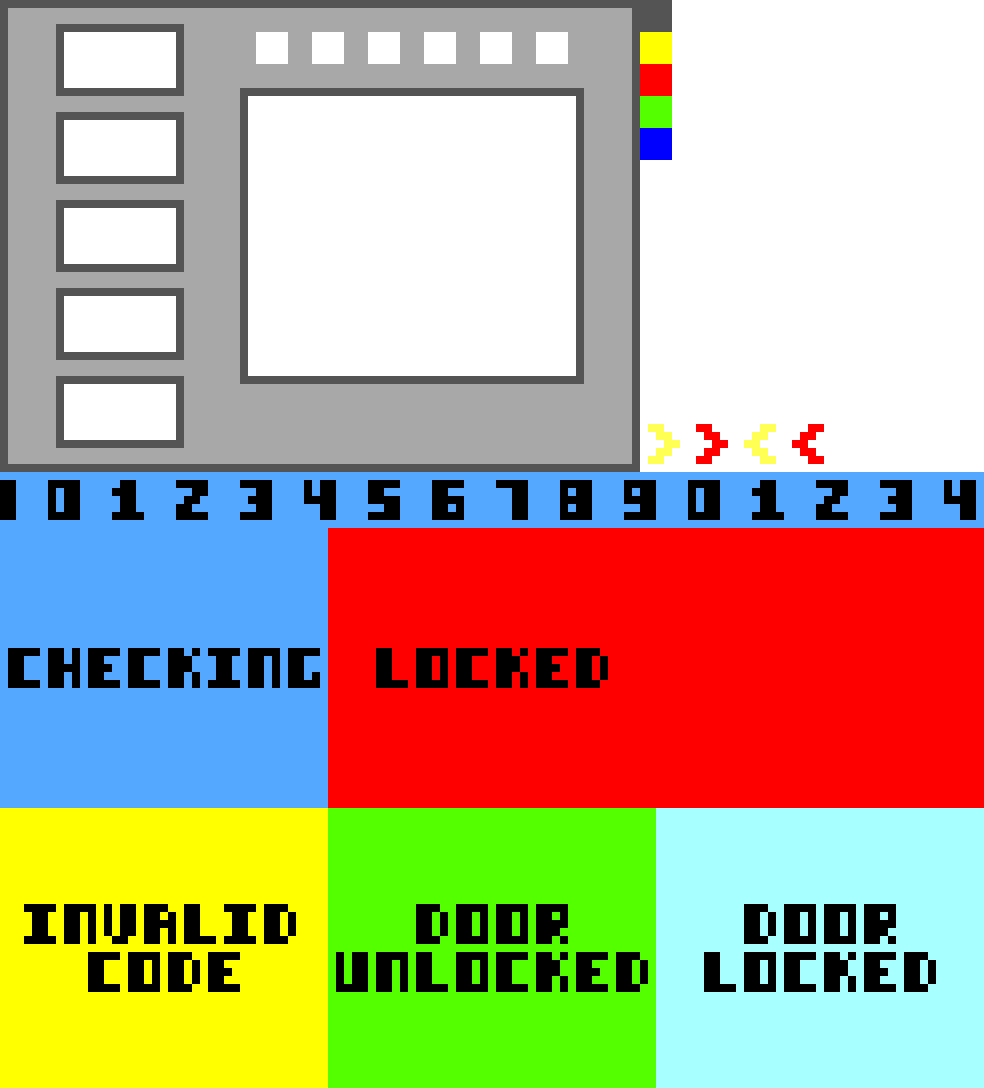

The winners

And finally (and maybe most importantly), on to the winners: 237 people managed to open the warehouse. That's a record high number!

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

| Year | |||||||||

From the correct answers, the following 10 winners were selected:

- Deborah

- Morgan

- Richard O

- Dave Budd

- Ben Boxall

- Alex Bolton

- Hannah Gray

- Simon English

- James Chapman

- Carly Chen

Congratulations! Your prizes will be on their way shortly.

The prizes this year include 2024 Advent calendar T-shirts. If you didn't win one, but would like one of these, I've made them available to buy at merch.mscroggs.co.uk alongside the T-shirts from previous years.

Additionally, well done to

100118220919, Aaron Stiff, Aglahir, Aidan Dodgson, Alan Buck, Alan Shotkin, alek2ander, Alex, Alex Hartz, Aline M. Lee, Allan Taylor, Anastasiia, Andrea Chlebikova, Andrew Brady, Andrew Roy, Andrew T, Andrew Thomson, Andy Ennaco, Ashley Jarvis, Austin Antoniou, Becky Russell, Ben, Ben Reiniger, Ben Tozer, Ben Weiss, Berl Steiner, Bill Varcho, Blake, BlueStorminator, Bogdan, Brian Wellington, Carmen, Carol Cooper, Cathy Hooper, Celer, Chris Eagle, Colin Beveridge, Colin Brockley, Corbin Groothuis, Dahé, Dan May, Dan Swenson, Dan Whitman, Daniel A, Daniel Low, Daphne, Dave, Dave Cowen, David, David Ault, David Banham, David Berardo, David Fox, David Kendel, Dhruv Pisharody, Dimitri Cacouris, Donald Anderson, Dylan Madisetti, Ean, Elizabeth Ann Madisetti, Ellie Winters, Elytre, Emily Troyer, Eoin Davey, Eric, Eric Kolbusz, Erick Lee, Erik Eklund, Evil Loanword, Ewan, Ewan Leeming, Fionn Woodcock, Frank Kasell, Fred Verheul, Gabriella Pinter, Gareth McCaughan, Gary M, Gary M. Gerken, George Witty, Gert-Jan, glocq, Green, Greg W., Guillermo Heras Prieto, Hannah Harris, Heerpal Sahota, Helen, Helen, Henri, Herschel, Holly Carnes, Håkon Balteskard, Iris Lasthofer, Ivan Andrus, Ivan Molotkov, Izzi, Jack, Jake, Jamas Enright, James Dolengewicz, Jamie van Otter, Jan Zemba, Jay Winter, JDev, Jean-Noël Monette, Jen Sparks, Jessica Marsh, Jim Ashworth, Joe Gage, Johan, Johannes C. Huber, John Drake, John Warwicker, Jon Palin, Jonathan Chaffer, Jonathan Thiele, Jorge del Castillo Tierz, Judith Werner, Justin Roughley, Kai, Kat Yates, Katerina Stergiopoulou, Katharine Velleman, Kelly Spoon, Kenneth McComas, Kevin Docherty, kil k, Kirsty Fish, Kristen Koenigs, Larry Goddard, Laura Kaplan, Lauren W., Lazar Ilic, Lincoln Ford, Lise Andreasen, Lizzie McLean, Logan Davis, Louis, Lucas Bowman, Lyra, Magnus Eklund, Marco van der Park, Mark Fisher, Mark Lydon, Martijn, Martin Harris, Martin Holtham, Martine Nome, Matthieu, Michael DeLyser, Mihai Zsisku, Mike Graczyk, Mike Hands, Miles Lunger, Millie, Mr J Winfield, Nadim Shawky, Nadine Chaurand, Naomi, Nazneen Molu, Neil Bastian, Neil M., Nick C, Nick Keith, Nikos Iakovidis, Noah Molder, Oliver Mills, olligobber, Pamela, Pete Chare, Peter Rowlett, Philip Corradi, Pierce R, Qaysed, Quinnifer, Rachel Sheridan, Rashi Gaba, Ray Arndorfer, Reuben, Riccardo Lani, Rob Reynolds, Roger Lipsett, Roni, Rosie P, Ross Ogilvie, Ruth Franklin, Sadie Sage Robinson, Sam Dreilinger, Sami Wannell, Sarah, Sarah B, Scott, Sean Henderson, Seth Cohen, Shannon, Shivanshi, stephen, Stephen Cappella, stephen kirkham, Steve Blay, Steven Richardson, Stuart MacDonald, Sumaya Felic, Tehnuka, The Connors of York, The Secret Kite, Tim Dufton, Tina, Todd, Tony Mann, Tony Palmer, Trevor Casey, tripleboleo, tt1991, Tyaka, Tyler St Clare, UsrBinPRL, Valentin VĂLCIU, Victor Miller, Vinayak, Vinny R, wilberforce314, William Huang, Yasha, Yuliya Nesterova, and Zoran Morrissey-Ralevic

who all also completed the Advent calendar but were too unlucky to win prizes this time or chose to not enter the prize draw.

See you all next December, when the Advent calendar will return.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Love the statistics! Thanks, again, for making the advent puzzle for us!

Jessica Marsh

Add a Comment

2025-01-01

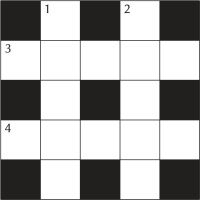

The puzzle on day 23 of this year's Advent calendar

is an interesting puzzle. After some hasty editing once it was pointed out to me that the original wording

was nonsense, the puzzle was this:

23 December

In a grid of squares, each square is friendly with itself and friendly with every square that is horizontally, vertically, or diagonally adjacent to it (and is not friendly with any other squares).

In a 5×5 grid, it is possible to colour 8 squares so that every square is friendly with at least two coloured squares:

It it not possible to do this by colouring fewer than 8 squares.

What is the fewest number of squares that need to be coloured in a

23×23 grid so that every square is friendly with at least two coloured squares?

As the squares that a square is friendly with are the same as those that would be attacked by a chess king on the square, the puzzle could be

re-expressed as: What is the fewest number of kings that need to be placed on a 23×23 chess board so that every square is attacked or occupied by at least two kings

(with no more than one king placed on each square)?

I came up with this puzzle while playing around with square grids in early November last year. I started by working out how many squares

need to be coloured for some smaller grids:

| Size of grid | Example grid | Minimum number of squares | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2×2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3×3 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4×4 | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5×5 | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6×6 | 10 |

This sequence was not on the OEIS, so I set about trying to work out the general formula for a term in this sequence.

Let \(a(n)\) be the minimum number of squared coloured for an \(n\) by \(n\) grid.

To work out the formula for \(a(n)\), we'll split the problem into 3 cases:

when \(n\) is a multiple of 3,

when \(n\) is 1 less than a multiple of 3,

when \(n\) is 2 less than a multiple of 3.

\(n=3k-1\)

When \(n\) is 1 less than a multiple of 3, it can be written as \(3k-1\) for some integer \(k\).

An upper bound

We can get an upper bound for the number of squares by finding a pattern of coloured squares that works, as the minimum number of squares will

then be at most this. For a 2×2 grid, we can colour 2 squares like this:

For a 5×5 grid, we can colour 8 squares like this:

For an 8×8 grid, we can colour 18 squares like this:

We can continue this pattern: in general for a \((3k-1)\)×\((3k-1)\) grid, we colour in pairs of squares with a gap of one between them in every third row.

This would involve colouring \(k\) rows of \(2k\) squares, so a total of \(2k^2\) squares.

Therefore \(a(3k-1)\leqslant2k^2\).

A lower bound

To obtain a lower bound, consider these squares in 5×5 grid:

or these squares in 8×8 grid:

The squares that neighbour these highlighted squares do not overlap, so two different squares must be coloured for each of these. This means that at least

2×4 (for a 5×5 grid) and 2×9 (for a 8×8 grid) squares must be coloured.

Continuing the pattern of highlighting the squares in every third row and every third column, we see that for a \((2k-1)\)×\((2k-1)\) grid, we must colour

at least \(2k^2\) squares, and so \(a(3k-1)\geqslant2k^2\).

The general term

Combining the lower and upper bounds, we can see that \(2k^2\leqslant a(3k-1)\leqslant2k^2\), and so \(a(3k-1)=2k^2\). As 23 is one less than a multiple of 3,

this first case is enough to solve the puzzle in the Advent calendar.

\(n=3k-2\)

When \(n\) is 2 less than a multiple of 3, it can be written as \(3k-2\) for some integer \(k\). We can obtain upper and lower bounds in a very similar way.

An upper bound

To get an upper bound, consider this pattern of coloured squares:

For a \((3k-2)\)×\((3k-2)\) grid, this pattern involves colouring \(k\) rows of \(2k\) squares, and so \(a(3k-2)\leqslant2k^2\).

A lower bound

To get a lower bound, consider this pattern of highlighted squares:

In exactly the same was as for \(n=3k-1\), we can see from this pattern that \(a(3k-2)\geqslant2k^2\).

The general term

Once again, our upper and lower bounds are equal, and so \(a(3k-2)=2k^2\).

\(n=3k\)

Here's where this question gets trickier/more interesting. If \(n\) is a multiple of 3, then it can be written at \(3k\) for some integer \(k\).

An upper bound

We can obtain an upper bound from this pattern:

For a \(3k\)×\(3k\) grid, this pattern involved colouring \(k\) rows of \(2k+1\) squares, and so \(a(3k)\leqslant2k^2+k\).

A lower bound

As in the previous sections, we can get an lower bound using this pattern:

For a \(3k\)×\(3k\) grid, the lower bound requires at least \(2k^2\) squares to be coloured.

We can increase this lower bound by 1 by looking at the

bottom right corner: the previous lower bound can colour at most one square adjacent to this, so there must be at least one more square next to that corner coloured.

So we have arrived at the lower bound \(a(3k)\geqslant2k^2+1\).

Bounds

In this case, the lower and upper bounds are not the same, so we are left with \(2k^2+1\leqslant a(3k)\leqslant 2k^2+k\). I've written

a Python script to compute terms of this sequence and have used it to find that:

- \(a(3)=3\)

- \(a(6)=10\)

- \(a(9)=21\)

- \(a(12)=36\)

For \(n=12\) and larger than this, the script takes a very long time, so I haven't checked any more terms.

The sequence and a conjecture

Overall, we've shown that:

$$

a(n) = \begin{cases}

2k^2&\text{if }n=3k-1\\

2k^2&\text{if }n=3k-2\\

\text{between }2k^2+1\text{ and }2k^2+k&\text{if }n=3k

\end{cases}

$$

This can be written slightly more succinctly as (where \(\lfloor x\rfloor\) means \(x\) rounded down to an integer):

$$

a(n) = \begin{cases}

\text{between }2\left(\frac{n}3\right)^2+1\text{ and }2\left(\frac{n}3\right)^2+\frac{n}3&\text{if }n\text{ is a multiple of 3}\\

2\left\lfloor\frac{n+2}3\right\rfloor^2&\text{if }n\text{ is not a multiple of 3}

\end{cases}

$$

I've submitted the sequence I have so far to the OEIS: A379726.

Based on the terms computed above, I conjecture that \(a(3k)=2k^2 + k\). If you have any ideas how I could increase my lower bound, or for any other way I could prove this, let me know!

Edit: OEIS sequence is published!

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

In attempting (and failing) to solve the puzzle when it first came out, I noticed that there were quite a few ways to colour the squares/place the kings for each minimum solution, some quite symmetrical and interesting. I wondered how many such "colourings" existed for each size of grid. And so because I apparently had nothing better to do over the weekend, I invested an inordinate amount of time coding up a script to bruteforce the number of colourings, and then a similarly inordinate amount of time optimizing it so I could get past a 5x5 grid. Here are the results:

2x2: 6

3x3: 2

4x4: 1296

5x5: 371

6x6: 8

Haven't been able to go any farther with my current script, but for what it's worth, here it is on GitHub.

2x2: 6

3x3: 2

4x4: 1296

5x5: 371

6x6: 8

Haven't been able to go any farther with my current script, but for what it's worth, here it is on GitHub.

Aaron

Here is my solution:

Project

Pre-built

Probably not super useful as I didn't attempt to prove my results, but I did come up with a general formula for odd-sized squares (with floor and ceiling functions), and perhaps the way I decoupled the two dimensions could be a useful approach for you.

Project

Pre-built

Probably not super useful as I didn't attempt to prove my results, but I did come up with a general formula for odd-sized squares (with floor and ceiling functions), and perhaps the way I decoupled the two dimensions could be a useful approach for you.

Dan Whitman

The conjecture is correct. Super-brief sketch proof: divide the grid into 3x3 boxes, aggregate those into horizontal and vertical strips of width 1 box = 3 squares; say a strip is "cheap" if it contains only 2k shaded squares (hence, exactly two per box). Working box by box from one end of a cheap strip to the other in both directions we see that the shaded squares must be in the middle transverse row/column of each box in such a strip. Hence there can't be both a cheap horizontal strip and a cheap vertical strip, because the box where they meet is overconstrained. So either all h-strips are not-cheap or all v-strips are not-cheap, and either of those gives you at least 2k2+k shaded squares.

(This, along with everything M.S. wrote, generalizes straightforwardly to arbitrary rectangular grids.)

(This, along with everything M.S. wrote, generalizes straightforwardly to arbitrary rectangular grids.)

g

Add a Comment

2024-12-22

I showed off and part-solved a prototype version of this puzzle with Katie Steckles in the fifteenth Finite Group livestream.

You can watch a recording of this stream, and watch our future streams if you sign up to

our Patreon.

I clearly haven't already made enough Christmas puzzles this year, so I've made another one. If you've used regular expressions before, head straight to

mscroggs.co.uk/regexmas to try the puzzle. If you've not, read on...

What is a regular expression

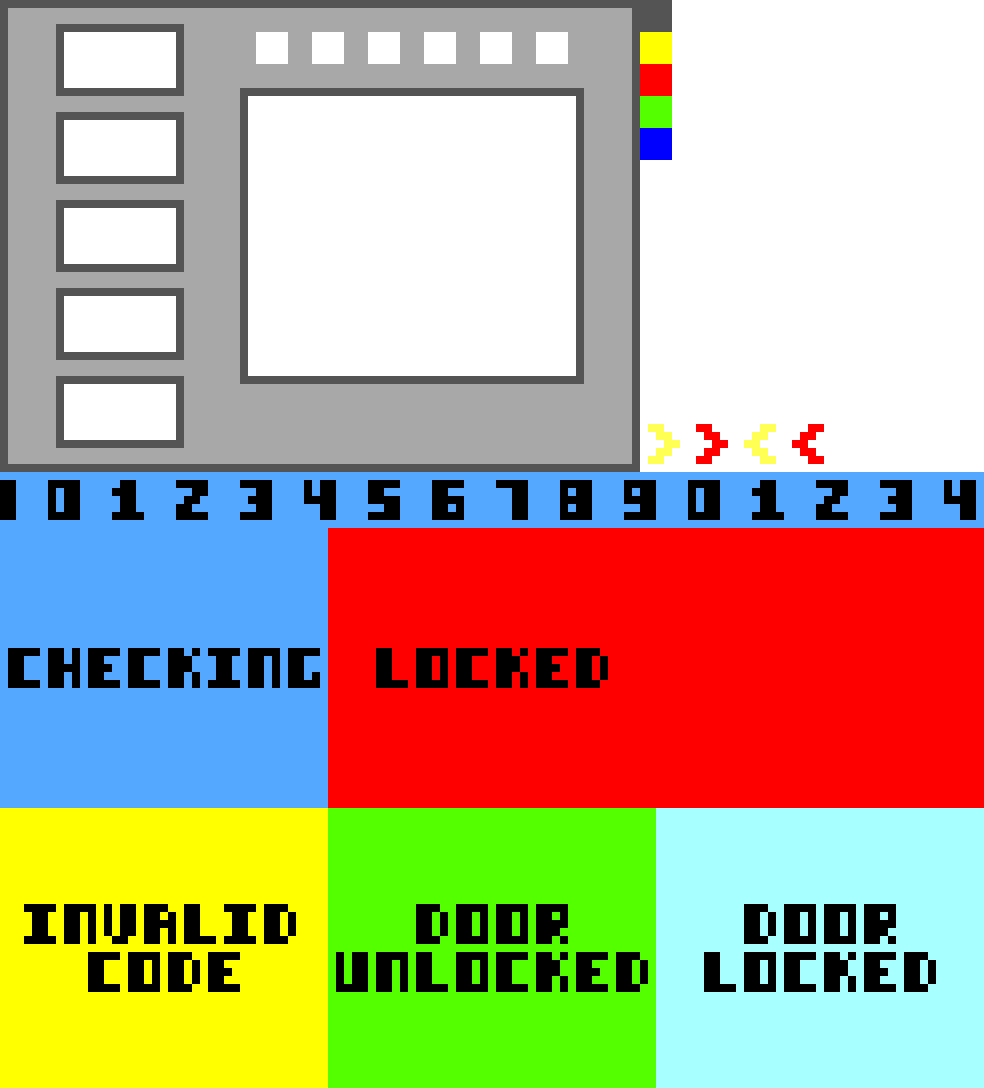

Regular expressions are strings of characters that can be used in multiple programming languages to validate text.

Regular expressions are usually written between two

/ characters. Between the slashes, characters have the following meaning:^(not inside square brackets) means the start of the text.$means the end of the text.- A set of characters are written between

[and]means any of these characters.

For example, the regular expression - A set of characters are written between

[^and]means any character except one of these. For example, the regular expression/^[^df]$/matches any character except d or f. ?means the previous item may or may not appear. For example, the regular expression/^ab?c$/matches "ac" or "abc".+means the previous item can appear one or more times. For example, the regular expression/^ab+c$/matches "abc", "abbc", "abbbc", and so on.*means the previous item can appear zero or more times. For example, the regular expression/^ab*c$/matches "ac", "abc", "abbc", and so on.{and}with a number between means the previous item can appear this number of times. For example, the regular expression/^ab{4}c$/matches "abbbbc".|means either the stuff to the left or the stuff to the right. For example, the regular expression/^ab|c$/matches "ab" or "c"..means any character. For example, the regular expression/^ab|.$/matches "ab" or any single character.(and)can be used to group together other symbols. Groups in brackets can be later referred to by writing\1,\2, etc to refer to the first, second, etc bracketed group. For example, the regular expression/^(a|b)\1$/matches "aa" or "bb".

/^[abc]$/ matches "a", "b", or "c".

The puzzle

My regular expression Christmas puzzle is shown below. You can either solve it on this page or at mscroggs.co.uk/regexmas

using the buttons or your keyboard, or you can download

this PDF of the puzzle.

In the grid below, write r, g, b, c, m, y, k, or w in every square so that:

- each row (reading left to right) satisfies the regular expression to the right of the row;

- each column (reading top to bottom) satisfies the regular expression below the column.

The squares containing an r will be coloured red,

those containing a g will be coloured green,

those containing a b will be coloured blue,

those containing a c will be coloured cyan,

those containing an m will be coloured magenta,

those containing a y will be coloured yellow,

those containing a k will be coloured black, and those containing a w will be left white.

/^w+yw+$/

/^([kw]+)[^kw]\1$/

/^(g|wwwg|gww)+.$/

/^wy?g*y+w+$/

/^((w|gg)(ww|g)){3}$/

/^[wg](w|g)[gw](.)\2+\1{2}$/

/^.g*[^y]$/

/^([gk][gk][gk])\1\1$/

/^yw+kw+y$/

/^w*b(bb)+w*$/

/^(w+)w?(bb?)\2\2\1$/

/^(www|bbb)+$/

/^w+gyw+$/

/^[wg]*y[wg]*$/

/^.*gwg.*gwb.*$/

/^[^g]+g+[^g]+$/

/^y?g+y?g+k?b+$/

/^[w]+g*w[^w]+$/

/^w+g+wg+[^g]+$/

/^w*yw*g+w*$/

/^w*y?g?y?w*$/

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment

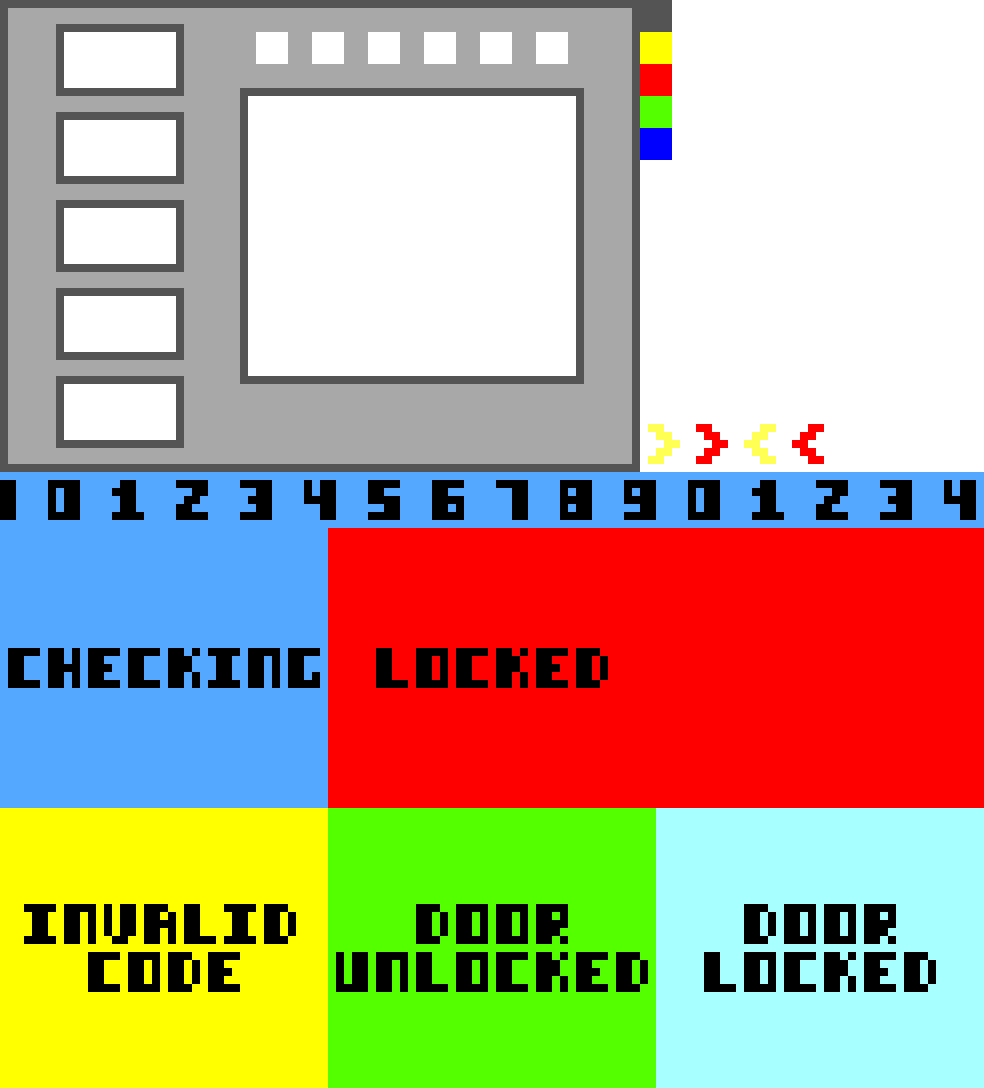

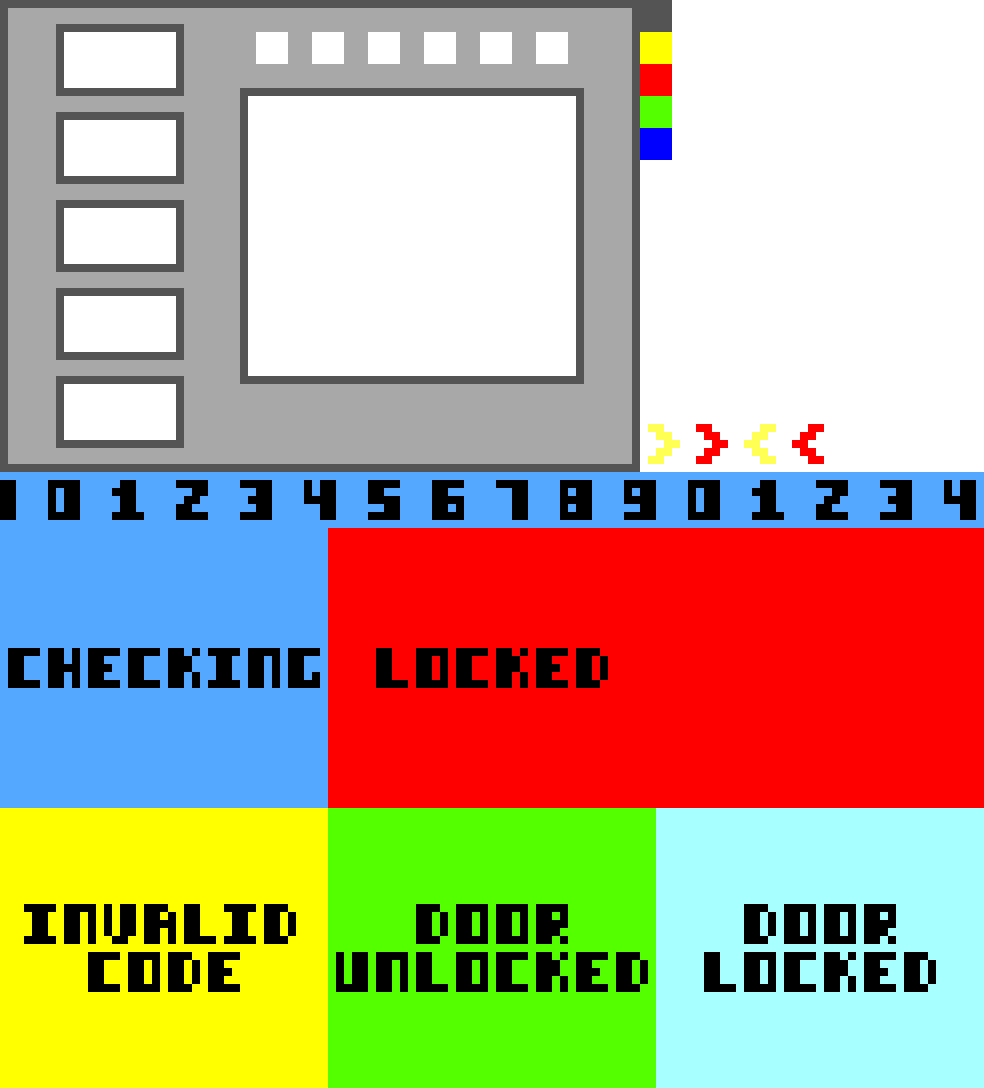

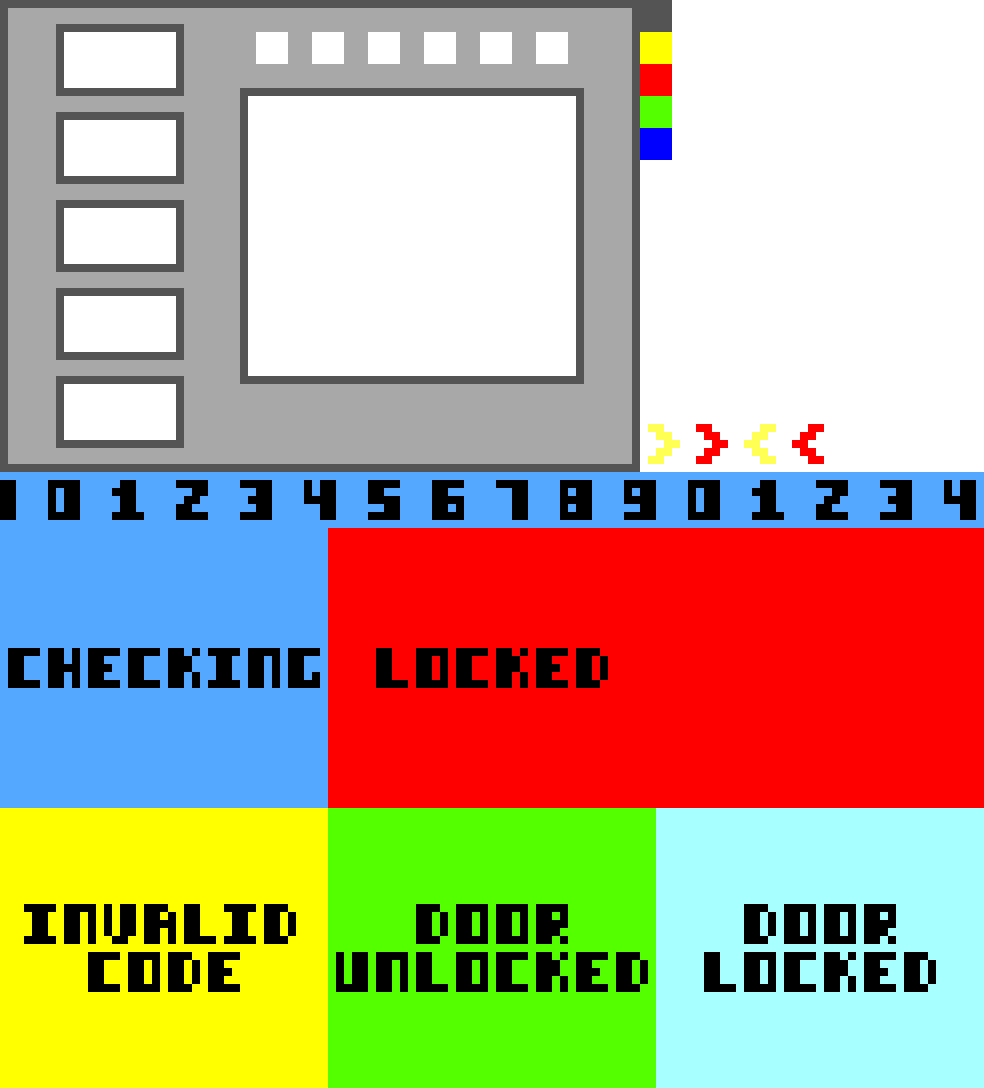

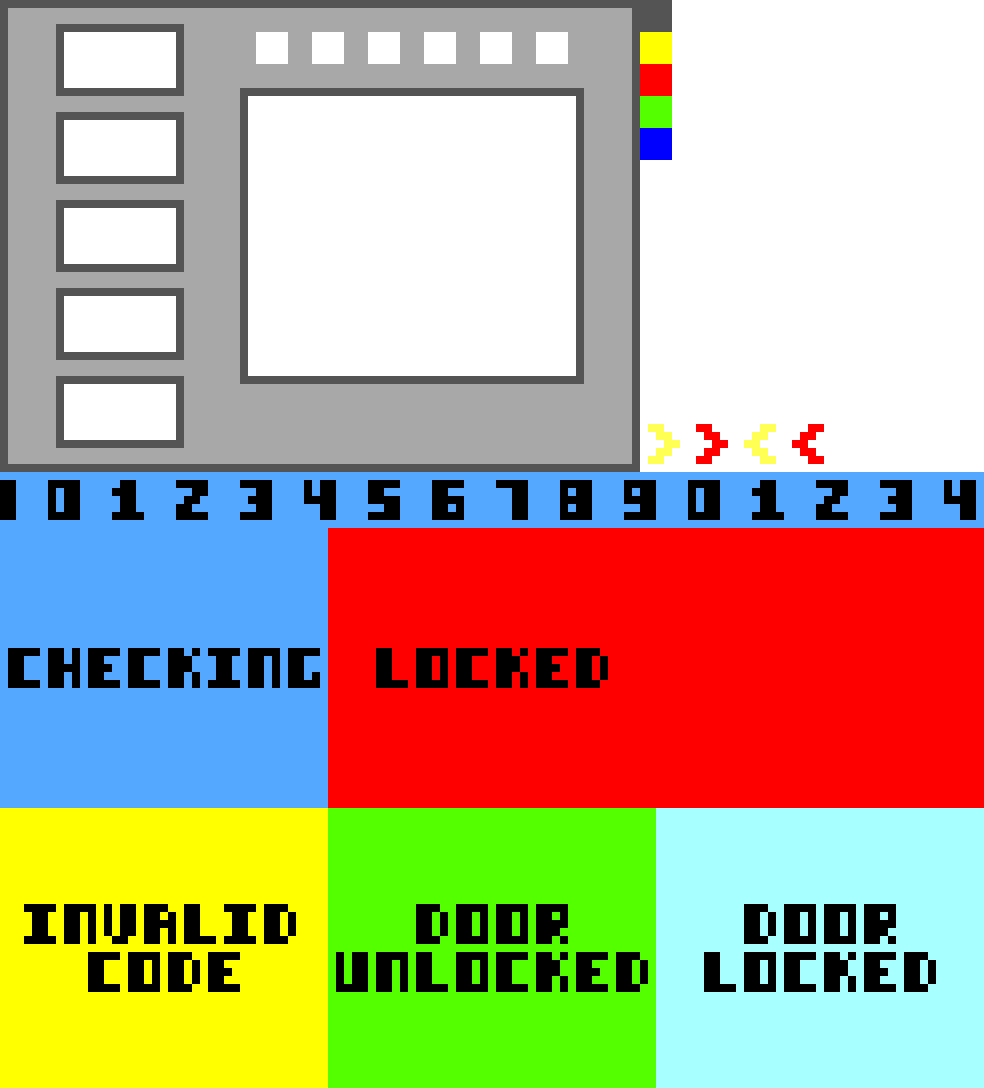

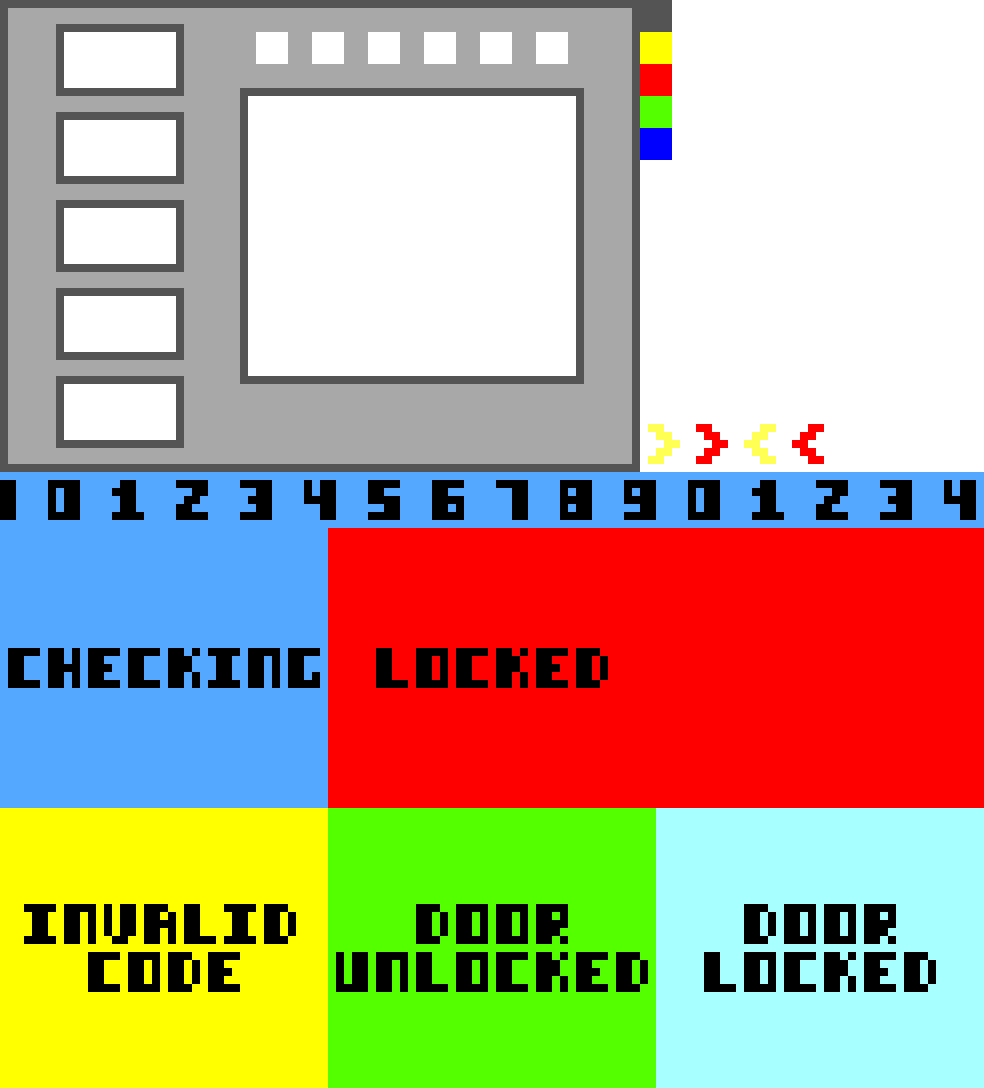

2024-12-04

As usual, I spent some time this November,

designing this year's Chalkdust puzzle Christmas card

(with some help from TD).

The card contains 10 puzzles. By splitting the answers into pairs of digits, then drawing lines between the dots on the cover for each pair of digits (eg if an answer is 201304, draw a line from dot 20 to dot 13 and another line from dot 13 to dot 4), you will reveal a Christmas themed picture. Colouring any region containing an even number of unused dots green and colour any region containing an odd number of unused dots red or blue will make the picture even nicer.

If you're in the UK and want some copies of the card to send to your maths-loving friends, you can order them at mscroggs.co.uk/cards.

If you want to try the card yourself, you can download this printable A4 pdf. Alternatively, you can find the puzzles below and type the answers in the boxes. The answers will automatically be used to join the dots and the appropriate regions coloured in...

| 1. | What is the largest number you can make by using the digits 1 to 4 to make two 2-digit numbers, then mutiplying the two numbers together? | Answer |

| 2. | What is the largest number you can make by using the digits 0 to 9 to make a 2-digit number and a 8-digit number, then mutiplying the two numbers together? | Answer |

| 3. | The expansion of \((2x+3)^2\) is \(4x^2+12x+9\). The sum of the coefficients of \(4x^2+12x+9\) is 25. What is the sum of the coefficients of the expansion of \((30x+5)^2\)? | Answer |

| 4. | What is the sum of the coefficients of the expansion of \((2x+1)^{11}\)? | Answer |

| 5. | What is the geometric mean of all the factors of 41306329? | Answer |

| 6. | What is the largest number for which the geometric mean of all its factors is 92? | Answer |

| 7. | What is the sum of all the factors of \(7^4\)? | Answer |

| 8. | How many numbers between 1 and 28988500000 have an odd number of factors? | Answer |

| 9. | Eve found the total of the 365 consecutive integers starting at 500 and the total of the next 365 consecutive integers, then subtracted the smaller total from the larger total. What was her result? | Answer |

| 10. | Eve found the total of the \(n\) consecutive integers starting at a number and the total of the next \(n\) consecutive integers, then subtracted the smaller total from the larger total. Her result was 22344529. What is the largest possible value of \(n\) that she could have used? | Answer |

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

I enjoyed solving problems for this card very much! Thanks a lot! I had a great time!

Happy New Year! Greetings from Ukraine.

Happy New Year! Greetings from Ukraine.

Anna

Matt, great card this year! Problems 1 and 2 are slightly ambiguous though in that you did not specify that each digit could only be used once.

I initially thought the answers were simply 44×44 = 1936 and 99×99999999 = 9899999901, respectively ????

I initially thought the answers were simply 44×44 = 1936 and 99×99999999 = 9899999901, respectively ????

Dan Whitman

I find that I can enter seven correct answers without issue. however, an eighth answer causes the entire tree to vanish.

I'm using Firefox on Windows 11.

I'm using Firefox on Windows 11.

hakon

@HJ: I can't reproduce that error on Firefox or Chrome on Ubuntu - although I did notice I'd left some debug outputting on, which I've now removed. Perhaps that was causing the issue.

If anyone else hits this issue, please let me know.

If anyone else hits this issue, please let me know.

Matthew

On my machine (Mac, using either Firefox or Chrome, including private mode so no plugins) the puzzle disappears when I complete the answers for 1, 3 and 9. I'm presuming my answers are correct -- the pattern they create is pretty clear and looks reasonable.

HJ

Add a Comment