Blog

2018-07-07

So you've calculated how much you should expect the World Cup sticker book to cost

and recorded how much it actually cost. You might be wondering what else you can do with your sticker book.

If so, look no further: this post contains 5 mathematical things involvolving your sticker book and stickers.

Test the birthday paradox

In a group of 23 people, there is a more than 50% chance that two of them will share a birthday. This is often called the birthday paradox, as the number 23 is surprisingly small.

Back in 2014 when Alex Bellos suggested testing the birthday paradox on World Cup squads, as there are 23 players in a World Cup squad. I recently discovered that even further back in 2012, James Grime made a video about the birthday paradox in football games, using the players on both teams plus the referee to make 23 people.

In this year's sticker book, each player's date of birth is given above their name, so you can use your sticker book to test it out yourself.

Kaliningrad

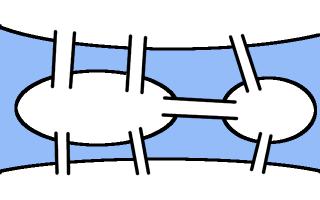

One of the cities in which games are taking place in this World Cup is Kaliningrad. Before 1945, Kaliningrad was called Königsberg. In Königsburg, there were seven bridges connecting four islands. The arrangement of these bridges is shown below.

The people of Königsburg would try to walk around the city in a route that crossed each bridge exactly one. If you've not tried this puzzle before, try to find such a route now before reading on...

In 1736, mathematician Leonhard Euler proved that it is in fact impossible to find such a route. He realised that for such a route to exist, you need to be able to pair up the bridges on each island so that you can enter the island on one of each pair and leave on the other. The islands in Königsburg all have an odd number of bridges, so there cannot be a route crossing each bridge only once.

In Kaliningrad, however, there are eight bridges: two of the original bridges were destroyed during World War II, and three more have been built. Because of this, it's now possible to walk around the city crossing each bridge exactly once.

A route around Kaliningrad crossing each bridge exactly once.

I wrote more about this puzzle, and using similar ideas to find the shortest possible route to complete a level of Pac-Man, in this blog post.

Sorting algorithms

If you didn't convince many of your friends to join you in collecting stickers, you'll have lots of swaps. You can use these to practice performing your favourite sorting algorithms.

Bubble sort

In the bubble sort, you work from left to right comparing pairs of stickers. If the stickers are in the wrong order, you swap them. After a few passes along the line of stickers, they will be in order.

In the insertion sort, you take the next sticker in the line and insert it into its correct position in the list.

In the quick sort, you pick the middle sticker of the group and put the other stickers on the correct side of it. You then repeat the process with the smaller groups of stickers you have just formed.

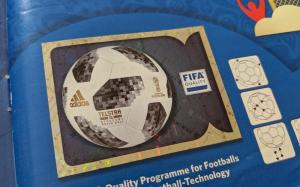

The football

Sticker 007 shows the official tournament ball. If you look closely (click to enlarge), you can see that the ball is made of a mixture of pentagons and hexagons. The ball is not made of only hexagons, as road signs in the UK show.

Stand up mathematician Matt Parker started a petition to get the symbol on the signs changed, but the idea was rejected.

If you have a swap of sticker 007, why not stick it to a letter to your MP about the incorrect signs as an example of what an actual football looks like.

Psychic pets

Speaking of Matt Parker, during this World Cup, he's looking for psychic pets that are able to predict World Cup results. Why not use your swaps to label two pieces of food that your pet can choose between to predict the results of the remaining matches?

Timber using my swaps to wrongly predict the first match

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

2019-06-19

@Matthew: Thank you for the calculations. Good job I ordered the stickers I wanted #IRN. 2453 stickers - that's more than the number you bought (1781) to collect all stickers!Milad

@Matthew: Here is how I calculated it:

You want a specific set of 20 stickers. Imagine you have already \(n\) of these. The probability that the next sticker you buy is one that you want is

$$\frac{20-n}{682}.$$

The probability that the second sticker you buy is the next new sticker is

$$\mathbb{P}(\text{next sticker is not wanted})\times\mathbb{P}(\text{sticker after next is wanted})$$

$$=\frac{662+n}{682}\times\frac{20-n}{682}.$$

Following the same method, we can see that the probability that the \(i\)th sticker you buy is the next wanted sticker is

$$\left(\frac{662+n}{682}\right)^{i-1}\times\frac{20-n}{682}.$$

Using this, we can calculate the expected number of stickers you will need to buy until you find the next wanted one:

$$\sum_{i=1}^{\infty}i \left(\frac{20-n}{682}\right) \left(\frac{662+n}{682}\right)^{i-1} = \frac{682}{20-n}$$

Therefore, to get all 682 stickers, you should expect to buy

$$\sum_{n=0}^{19}\frac{682}{20-n} = 2453 \text{ stickers}.$$

You want a specific set of 20 stickers. Imagine you have already \(n\) of these. The probability that the next sticker you buy is one that you want is

$$\frac{20-n}{682}.$$

The probability that the second sticker you buy is the next new sticker is

$$\mathbb{P}(\text{next sticker is not wanted})\times\mathbb{P}(\text{sticker after next is wanted})$$

$$=\frac{662+n}{682}\times\frac{20-n}{682}.$$

Following the same method, we can see that the probability that the \(i\)th sticker you buy is the next wanted sticker is

$$\left(\frac{662+n}{682}\right)^{i-1}\times\frac{20-n}{682}.$$

Using this, we can calculate the expected number of stickers you will need to buy until you find the next wanted one:

$$\sum_{i=1}^{\infty}i \left(\frac{20-n}{682}\right) \left(\frac{662+n}{682}\right)^{i-1} = \frac{682}{20-n}$$

Therefore, to get all 682 stickers, you should expect to buy

$$\sum_{n=0}^{19}\frac{682}{20-n} = 2453 \text{ stickers}.$$

Matthew

@Matthew: Yes, I would like to know how you work it out please. I believe I have left my email address in my comment. It seems like a lot of stickers if you are just interested in one team.

Milad

@Milad: Following a similiar method to this blog post, I reckon you'd expect to buy 2453 stickers (491 packs) to get a fixed set of 20 stickers. Drop me an email if you want me to explain how I worked this out.

Matthew

Thanks for the maths, but I have one probability question. How many packs would I have to buy, on average, to obtain a fixed set of 20 stickers?

Milad

Add a Comment

2018-06-16

This year, like every World Cup year, I've been collecting stickers to fill the official Panini World Cup sticker album.

Back in March, I calculated that I should expect it to cost £268.99 to fill this year's album (if I order the last 50 stickers).

As of 6pm yesterday, I need 47 stickers to complete the album (and have placed an order on the Panini website for these).

So... How much did it cost?

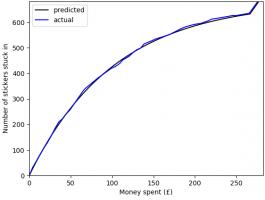

In total, I have bought 1781 stickers (including the 47 I ordered) at a cost of £275.93. The plot below shows

the money spent against the number of stickers stuck in, compared with the what I predicted in March.

To create this plot, I've been keeping track of exactly which stickers were in each pack I bought. Using this data, we can

look for a few more things. If you want to play with the data yourself, there's a link at the bottom to download it.

Swaps

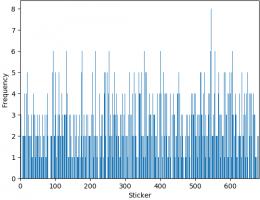

The bar chart below shows the number of copies of each sticker I got (excluding the 47 that I ordered). Unsurprisingly, it looks a lot like

random noise.

The sticker I got most copies of was sticker 545, showing Panana player Armando Cooper.

I got swaps of 513 different stickers, meaning I'm only 169 stickers short of filling a second album.

First pack of all swaps

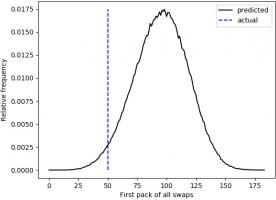

Everyone who has every done a sticker book will remember the awful feeling you get when you first get a pack of all swaps.

For me, the first time this happened was the 50th pack. The plot below shows when the first pack of all swaps occurred in 500,000 simulations.

Looks like I was really quite unlucky to get a pack of all swaps so soon.

Duplicates in a pack

In all the 345 packs that I bought, there wasn't a single pack that contained two copies of the same sticker.

In fact, I don't remember ever getting two of the same sticker in a pack. For a while I've been wondering if this is because Panini

ensure that packs don't contain duplicates, or if it's simply very unlikely that they do.

If it was down to unlikeliness, the probability of having no duplicates in one pack would be:

\begin{align}

\mathbb{P}(\text{no duplicates in a pack}) &= 1 \times\frac{681}{682}\times\frac{680}{682}\times\frac{679}{682}\times\frac{678}{682}\\

&= 0.985

\end{align}

and the probability of none of my 345 containing a duplicate would be:

\begin{align}

\mathbb{P}(\text{no duplicates in 345 packs})

&= 0.985^{345}\\

&= 0.00628

\end{align}

This is very very small, so it's safe to conclude that Panini do indeed ensure that packs do not contain duplicates.

The data

If you'd like to have a play with the data yourself, you can download it here. Let me know if

you do anything with it...

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment

2018-03-22

Back in 2014, I worked out the cost of filling an official Panini World Cup 2014 sticker book. Today, the 2018 sticker book was relased: compared to four years ago, there are more stickers to collect and the prices have all changed. So how much should we expect it to cost us to fill the album this time round?

How many stickers will I need?

There are 682 stickers to collect. Imagine you have already stuck \(n\) stickers into your album. The probability that the next sticker you buy is new is

$$\frac{682-n}{682}.$$

The probability that the second sticker you buy is the next new sticker is

$$\mathbb{P}(\text{next sticker is not new})\times\mathbb{P}(\text{sticker after next is new})$$

$$=\frac{n}{682}\times\frac{682-n}{682}.$$

Following the same method, we can see that the probability that the \(i\)th sticker you buy is the next new sticker is

$$\left(\frac{n}{682}\right)^{i-1}\times\frac{682-n}{682}.$$

Using this, we can calculate the expected number of stickers you will need to buy until you find a new one:

$$\sum_{i=1}^{\infty}i \left(\frac{682-n}{682}\right) \left(\frac{n}{682}\right)^{i-1} = \frac{682}{682-n}$$

Therefore, to get all 682 stickers, you should expect to buy

$$\sum_{n=0}^{681}\frac{682}{682-n} = 4844 \text{ stickers}.$$

How much will this cost?

You can buy the following [source]:

- Starter pack (an album and 31 stickers) for £3.99

- Sticker packs (5 stickers) for 80p

- Sticker multipacks (30 stickers) for £4.50

First of all you'll need to buy the starter pack, as you need an album to stick everything in. This comes with 31 stickers; we should expect to buy 4813 more stickers after this.

The cheapest way to buy these stickers is to buy them in multipacks for 15p per sticker. This gives a total expected cost of filling the sticker album of £725.94. (Although if your local newsagent doesn't stock the multipacks, buying 80p packs to get these stickers will cost you £774.07.)

What if I order the last 50 stickers?

If you'd like to spend a bit less on the sticker book, Panini lets you order the last 50 stickers to complete your album. This is very helpful as these last 50 stickers are the most expensive.

You can order missing stickers from the Panini website for 22p per sticker's sticker ordering service for the 2018 World Cup doesn't appear to be online yet; but based on other recent collections, it looks like ordered stickers will cost 16p each, with £1 postage per order.

Ordering the last 50 stickers reduces the expected number of other stickers you need to buy to

$$\sum_{n=0}^{631}\frac{682}{682-n} = 1775 \text{ stickers}.$$

This reduces the expected overall cost to £291.03. So I've just saved you £434.91.

What if I order more stickers?

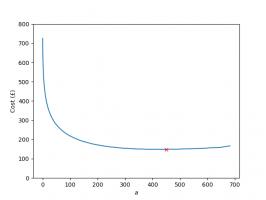

Of course, if you're willing to completely give up on your morals, you could order more than one batch of 50 stickers from Panini. This raises the question: how many should you order to minimise the expected cost.

If you order the last \(a\) stickers, then you should expect to pay:

- £3.99 for the album and first 31 stickers

- £\(\displaystyle0.15\left(\sum_{n=1}^{681-a}\frac{682}{682-n}-31\right)\) for other stickers you need

- £\(\displaystyle \left(0.16a+\left\lceil \frac{a}{50}\right\rceil\right)\) to order the last \(a\) stickers

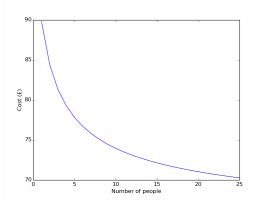

The total expected cost of filling your album for different values of \(a\) is shown in the graph below.

The red cross shows the point at which the album is cheapest: this is when the last 550 stickers are ordered, giving a total expected cost of £120.18. That's another £170.85 I've saved you. You're welcome.

Still, ordering nearly all stickers to minimise the cost doesn't sound like the most fun way to complete the sticker book, so you probably need to order a few less than this to maximise your fun.

What about swaps?

Of course, you can also get the cost of filling the book down by swapping your spare stickers with friends. In 2016, I had a go at simulating filling a sticker book with swapping and came to the possibly obvious conclusion that the more friends you have to swap with, the cheaper filling the book will become.

My best advice for you, therefore, is to get out there right now and start convinding your friends to join you in collecting stickers.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

@RM: It would slightly reduce the expected cost I think, but I need to do some calculations to make sure.

I'm not certain whether they guarantee that there are no duplicates in a pack or just it's very unlikely... Follow up post looking into this coming soon

I'm not certain whether they guarantee that there are no duplicates in a pack or just it's very unlikely... Follow up post looking into this coming soon

Matthew

Helpful article!! My head always go into a spine with probability, but does the fact that you would not get a double within a pack affect the overall strategy or cost? My head says this is an another advantage of buying 30 packs over the 5.

RM

Add a Comment

2016-05-04

Back in 2014, I calculated the expected cost of

filling Panini world cup sticker album. I found that you should expect to buy

4505 stickers, or 1285 if you order the last 100 from the Panini website (this

includes the last 100). This would cost £413.24 or £133.99

respectively.

Euro 16 is getting close, so it's sticker time again. For the Euro 16

album there are 680 stickers to collect, 40 more than 2014's 640 stickers.

Using the same calculation method as before,

to fill the Euro 16 album, you should expect to buy 4828

stickers (£442.72), or 1400 (£134.32) if you order the last 100.

This, however, does not tell the whole story. Anyone who has collected

stickers as a child or an adult will know that half the fun comes from

swapping your doubles with friends. Getting stickers this way is not

taken into account in the above numbers.

Simulating a sticker collection

Including swaps makes the situation more complicated: too complicated

to easily calculate the expected cost of a full album. Instead, a different

method is needed. The cost of filling an album can be estimated by

simulating the collection lots of times and taking the average of the cost of

filling the album in each simulation. With enough simulations, this estimate

will be very close the the expected cost.

To get an accurate estimation, simulations are run,

calculating the running average as they go, until the running averages after recent simulations

are close together. (In the examples, I look for the four most recent running averages to be within 0.01.)

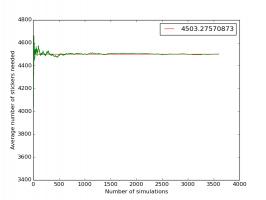

The plot below shows how the running average changes as more simulations are performed.

The simulations estimate the number of stickers needed as 4500. This is

very close to the 4505 I calculated last year.

Now that the simulations are set up, they can be used to see what happens if you have friends to swap with.

What should I do?

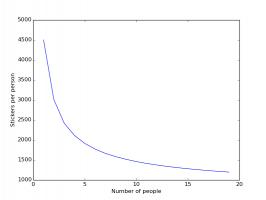

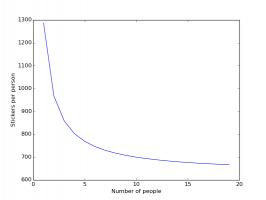

The plots below shows how the number of stickers you need to buy each changes based on how many friends you have.

Stickers needed if you and your friends order no stickers.

Stickers needed if you and your friends all order the last 100 stickers. The last 100 are not counted.

In both these cases, having friends reduces the number of stickers you need to buy significantly, with your first few friends

making the most difference.

Ordering the last 100 stickers looks to be a better idea than ordering no stickers. But how many stickers should you order to

minimise the cost? When you order stickers, you are guaranteed to get those that you need, but they cost more: ordered stickers cost 14p

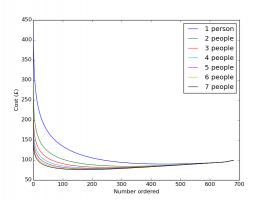

each, while stickers in 6 pack multipacks come out at just 9.2p each. The next plot shows how the cost changes based on how many you order.

The expected cost of filling an album based on number of people in group and number of stickers ordered.

Each of the coloured curves represents a group of a different size. For each group, ordering no stickers works out the most

expensive—this is expected as so many stickers must be bought to find the last few stickers—and ordering all the stickers also works

out as not the best option. The best number to order

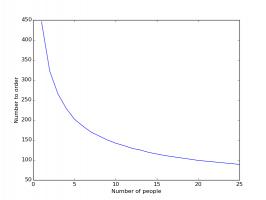

is somewhere in the middle, where the curve reaches its lowest point. The minimum points on each of these curves are summarised in the

next plots:

How the number you should order changes with the number of people in the group.

How the cost changes with the number of people in the group.

Again, having friends to swap with dramatically reduces the cost of filling an album. In fact, it will almost definitely pay off in future

swaps if you go out right now and buy starter packs for all your friends...

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment

2015-10-21

This post also appeared on the Chalkdust Magazine blog.

If you're like me, then you will be disappointed that all of the home nations have been knocked out of the Rugby World Cup. If you're really like me, doing some maths related to rugby will cheer you up...

The scoring system in rugby awards points in packets of 3, 5 and 7. This leads a number of interesting questions that you can find in my guest puzzle on Alex Bellos's Guardian blog. In this blog post, we will focus on another area of rugby: conversion kicking.

Conversion kicks

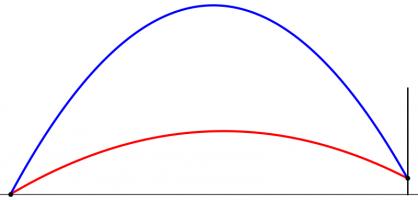

When a try is scored by putting the ball down behind the line, the scoring team gets to take a conversion kick. This kick must be taken in line with where the try was scored but it is up to the kicker how far away the kick should be taken. But how far back should the ball be taken to make the kick easiest?

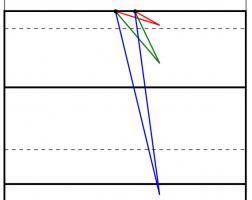

Too close (red) and too far away (blue) will give small angles to aim at. Somewhere in the middle is needed (green).

One way to answer this question is to look to maximise the angle between the posts which the kicker will have to aim at: if the kick is taken too close to or too far from the goal line there will be a very thin angle to aim at. Somewhere between these extremes there will be a maximum angle to aim at.

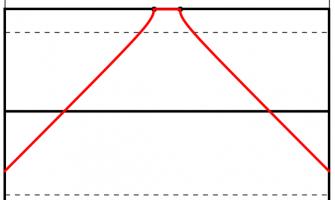

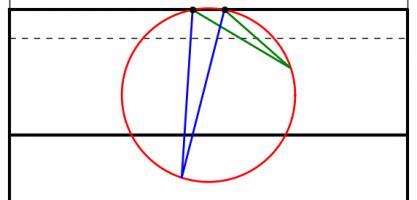

When looking to maximise this angle, we can use one of the 'circle theorems' which have tormented many generations of GCSE maths students: 'angles subtended by the same arc at the circumference are equal'. This means that if a circle is drawn going through both posts, then the angle made at any point on this circle will be the same.

The angles made by the red and blue lines are equal because 'angles subtended by the same arc at the circumference are equal'.

A larger circle drawn through the posts will give a smaller angle. If a vertical line is drawn which just touches the right of the circle, then the point at which it touches the circle will be the best place on this line to take a kick. This is because any other point on the line will be on a larger circle and so make a smaller angle.

Using this method for circles of different sizes leads to the following diagram, which shows where the kick should be taken for every position a try could be scored:

This, however, is not the best place to take the kick.

Taking account of height

When a try is scored near the posts, the above method recommends a position from where the ball must be kicked at an impossibly steep angle to go over. To deal with this problem, we are going to have to look at the situation from the side.

When kicked, the ball will travel along a parabola (ignoring air resistance and wind as their effects will be small[citation needed]). Given a distance from the posts, there will be two angles which the ball can be kicked at and just make it over the bar. Kicking at any angle between these two will lead to a successful conversion. Again, we have an angle which we would like to maximise.

However, the position where this angle is maximised is very unlikely to also maximise the angle we looked at earlier. To find the best place to kick from, we need to find a compromise point where both angles are quite big.

To do this, imagine that the kicker is standing inside a large sphere. For each point on the sphere, kicking the ball at the point will either lead to it going over or missing. We can draw a shape on the sphere so that aiming inside the shape will lead to scoring. Our sensible kicker will aim at the centre of this shape.

But our kicker will not be able to aim perfectly: there will be some random variation. We can predict that this variation will follow a Kent distribution, which is like a normal distribution but on the surface of a sphere. We can use this distribution to calculate the probability that our kicker will score. We would like to maximise this probability.

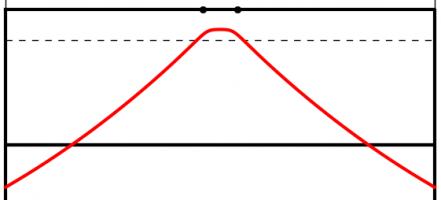

The Kent distribution can be adjusted to reflect the accuracy of the kicker. Below are the optimal kicking positions for an inaccurate, an average and a very accurate kicker.

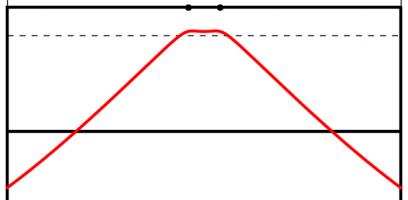

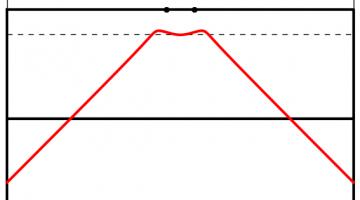

The best place to take a kick for a bad kicker (top), an average kicker (middle) and a good kicker (bottom). All the kickers kick the ball at 30m/s.

As you might expect, the less accurate kicker should stand slightly further forwards to make it easier to aim. Perhaps surprisingly, the good kicker should stand further back when between the posts than when in line with the posts.

The model used to create these results could be further refined. Random variation in the speed of the kick could be introduced. Or the kick could be made to have more variation horizontally than vertically: there are parameters in the Kent distribution which allow this to be easily adjusted. In fact, data from players could be used to determine the best position for each player to kick from.

In addition to analysing conversions, this method could be used to determine the probability of scoring 3 points from any point on the pitch. This could be used in conjunction with the probability of scoring a try from a line-out to decide whether kicking a penalty for the posts or into touch is likely to lead to the most points.

Although estimating the probability of scoring from a line-out is a difficult task. Perhaps this will give you something to think about during the remaining matches of the tournament.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment