Blog

2023-09-02

This week, I've been at Talking Maths in Public (TMiP) in Newcastle. TMiP is a conference for anyone involved

in—or interested in getting involved in—any sort of maths outreach, enrichment, or public engagement activity. It was really good, and I highly recommend coming to TMiP 2025.

The Saturday morning at TMiP was filled with a choice of activities, including a puzzle hunt written by me: the Tyne trial.

At the start/end point of the Tyne trial, there was a locked box with a combination lock. In order to work out the combination for the lock, you needed to find some clues hidden around

Newcastle and solve a few puzzles.

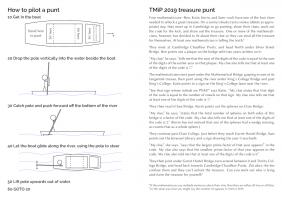

Every team taking part was given a copy of these instructions.

Some people attended TMiP virtually, so I also made a version of the Tyne trial that included links to Google Street View and photos from which the necessary information could be obtained.

You can have a go at this at mscroggs.co.uk/tyne-trial/remote. For anyone who wants to try the puzzles without searching through virtual Newcastle,

the numbers that you needed to find are:

- Clue #1: \(a\) is 9.

- Clue #2: \(b\) is 5.

- Clue #3: \(c\) is 1838.

- Clue #4: \(d\) is 1931.

- Clue #5: \(e\) is 1619.

- Clue #6: \(f\) is 48.

- Clue #7: \(g\) is 1000.

The solutions to the puzzles and the final puzzle are below. If you want to try the puzzles for yourself, do that now before reading on.

Puzzle for clue #2: Palindromes

We are going to start with a number then repeat the following process: if the number you have is a palindrome, stop;

otherwise add the number to itself backwards.

For example, if we start with 219, then we do: $$219\xrightarrow{+912}1131\xrightarrow{+1311}2442.$$

If you start with the number \(10b+9\) (ie 59), what palindrome do you get?

(If you start with 196, it is unknown whether you will ever get a palindrome.)

Puzzle for clue #3: Mostly ones

There are 12 three-digit numbers whose digits are 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 with exactly two digits that are ones.

How many \(c\)-digit (ie 1838-digit) numbers are there whose digits are 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 with exactly \(c-1\) digits (ie 1837) that are ones?

Puzzle for clue #4: is it an integer?

The largest value of \(n\) such that \((n!-2)/(n-2)\) is an integer is 4. What is the largest value of \(n\) such that

\((n!-d)/(n-d)\) (ie \((n!-1931)/(n-1931)\)) is an integer?

Puzzle for clue #5: How many steps?

We are going to start with a number then repeat the following process:

if we've reached 0, stop; otherwise subtract the smallest prime factor of the current number.

For example, if we start with 9, then we do: $$9\xrightarrow{-3}6\xrightarrow{-2}4\xrightarrow{-2}2\xrightarrow{-2}0.$$ It took 4 steps to get to 0.

What is the smallest starting number such that this process will take \(e\) (ie 1619) steps?

Puzzle for clue #6: Four-digit number

I thought of a four digit number. I removed a

digit to make a three digit number, then added my two numbers together.

The result is \(200f+127\) (ie 9727). What was my original number?

Puzzle for clue #7: Dice

If you roll two six-sided fair dice, the most likely total is 7. What is the most likely total if you rolled \(1470+g\) (ie 2470) dice?

The final puzzle

The final puzzle involves using the answers to the five puzzles to find the four digit code that

opens the box (and the physical locked box that was in the library on

Saturday. To give hints to this code, each clue was given a "score".

The score of a number is the number of values of \(i\) such that the \(i\)th digit

of the code is a factor of the \(i\)th digit of the number.

For example, if the code was 1234, then the score of the number 3654 would be 3 (because

1 is a factor of 3; 2 is a factor of 6; and 4 is a factor of 4).

The seven clues to the final code are:

- Clue #1: 6561 scores 2 points.

- Clue #2: 1111 scores 0 points.

- Clue #3: 7352 scores 1 points.

- Clue #4: 3562 scores 1 points.

- Clue #5: 3238 scores 1 points.

- Clue #6: 8843 scores 1 points.

- Clue #7: 8645 scores 3 points.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment

2021-09-25

A few weeks ago, I (virtually) went to Talking Maths in Public (TMiP). TMiP is a conference for anyone involved

in—or interested in getting involved in—any sort of maths outreach, enrichment, or public engagement activity. It was really good, and I highly recommend coming to TMiP 2023.

The Saturday morning at TMiP was filled with a choice of activities, including a puzzle hunt written by me. Each puzzle required the solver to first find a clue hidden in

the conference's Gather-Town-powered virtual Edinburgh (built by the always excellent Katie Steckles), then solve the puzzle to reveal a clue to the final code. Once the final code was found, the solvers could enter

a secret area in the Gather Town space.

The puzzles for the puzzle hunt can be found at mscroggs.co.uk/tmip. For anyone who doesn't have access to the Gather Town space, the numbers that are hidden in the space are:

- Puzzle 1: The mathematician (Thomas Bayes) died in 1761.

- Puzzle 2: The sign claims that Arthur's seat is 1288 links tall.

- Puzzle 3: The sign claims that the maximum capicity of the museum is 2449 people.

- Puzzle 4: Dynamic Earth became a charitable trust in 94.

- Puzzle 5: The 102 bus goes to Dumfries.

The solutions to the five puzzles, and the final puzzle are below. If you want to try the puzzles for yourself, do that now before reading on.

Puzzle 1: The strange shop

A shop has a very strange pricing model. If you buy \(k\) items, then the price (in pence) is decided as follows:

- If \(k\) is prime, then the price is \(k\) pence.

- If \(k\) is not prime, then double \(k\) and add one:

- If the result is prime, that is the price.

- If the result is not prime, keep doubling and adding one until a prime is reached.

You enter the shop with 1761 pence and buy 28 items.

How many pence do you leave the shop with?

Fun fact: If you try to buy 509202 items from the shop, then the shopkeeper cannot work out a price,

as a prime is never reached. It is currently unknown if this is the smallest number of items that

this is true for.

Puzzle 2: The homemade notebook

You make a homemade notebook with 1288 pages:

You take a stack of 1288/4 pieces of paper and fold the entire stack in half so that

each piece of paper makes four pages in the notebook. You number the pages:

you write the number 1 on the front cover, 2 on the inside front cover, and so on

until you write 1288 on the back cover.

While you are looking for your stapler, a strong wind blows the pieces of paper all

over the floor. You pick up one of the pieces of paper and add up the two numbers

you wrote on one side of it.

What is the largest total you could have obtained?

Puzzle 3: The overlapping triangles

You draw three circles that all meet at a point:

You then draw two triangles. The smaller red triangle's vertices are the centres of the circles. The larger blue triangle's vertices are at the points on each circle diametrically opposite the point where all three circles meet:

The area of the smaller red triangle is 2449.

What is the area of the larger blue triangle?

The odd factors

You write down the integers from 94+1 to 2×94 (including 94+1 and 2×94). Under each number, you write down its largest odd factor*.

What is the sum of all the odd factors you have written?

* In this puzzle, factors include 1 and the number itself.

Hint: Doing what the puzzle says may take a long time. Try doing this will some smaller values than 94 first and see if you can spot a shortcut.

The sandwiched quadratic

You know that \(f\) is a quadratic, and so can be written as \(f(x)=ax^2+bx+c\) for some real numbers \(a\), \(b\), and \(c\);

but you've forgetten exactly which quadratic it is. You remember that for all real values of \(x\), \(f\) satisfies

$$\tfrac{1}{4}x^2+2x-8\leqslant f(x)\leqslant(x-2)^2.$$

You also remember that the minimum value of \(f\) is at \(x=0\).

What is f(102)?

The final puzzle

The final puzzle involves using the answers to the five puzzles to find a secret four digit passcode is made up of four non-zero digits. To turn them into clues,

the answers to each puzzle were scored as follows:

Each digit in an answer that is also in the passcode and in the same position in both scores two points; every digit in the answer that is also in the passcode but in a different position scores 1 point. For example, if the passcode was 3317, then:

- 4686 would score 0 points (no digits correct);

- 4676 would score 1 point (7 is a correct digit but in the wrong position);

- 4616 would score 2 points (1 is a correct digit in the correct position);

- 4343 would score 3 points (one of the 3s is a correct digit in the correct position, the other 3 is a correct digit in the wrong position);

- 7333 would score 4 points (one of the 3s is a correct digit in the correct position, the 7 and one of the other 3s are correct digits in wrong positions. Note that the third three scores nothing);

- and 1733 would score 4 points (all four digits are correct digits in wrong positions).

The five clues to the final code are:

- Puzzle 1: 1298 scores 3 points.

- Puzzle 2: 1289 scores 3 points.

- Puzzle 3: 9697 scores 3 points.

- Puzzle 4: 8836 scores 1 point.

- Puzzle 5: 5198 scores 4 points.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Small nitpick on problem 1 fun fact. I think you meant 509202. 509203 is already prime so the price would be 509203. The way you set up the problem (2a_n+1) only gets to (k*2^n-1) if you start with k-1, so your k needs to be one smaller than the Wikipedia's k.

Dan

Add a Comment

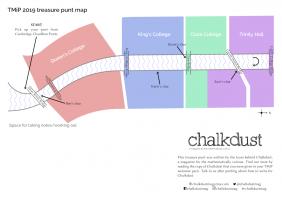

2019-09-01

This week, I've been in Cambridge for Talking Maths in Public (TMiP). TMiP is a conference for anyone involved in—or interested in getting involved

in—any sort of maths outreach, enrichment, or public engagement activity. It was really good, and I highly recommend coming to TMiP 2021.

The Saturday morning at TMiP was filled with a choice of activities, including a treasure punt (a treasure hunt on a punt) written by me. This post contains the puzzle from the treasure punt for

anyone who was there and would like to revisit it, or anyone who wasn't there and would like to give it a try. In case you're not current in Cambridge on a punt, the clues that you were meant to

spot during the punt are given behing spoiler tags (hover/click to reveal).

Instructions

Each boat was given a copy of the instructions, and a box that was locked using a combination lock.

If you want to make your own treasure punt or similar activity, you can find the LaTeX code used to create the instructions and the Python code I used to check that the puzzle

has a unique solution on GitHub. It's licensed with a CC BY 4.0

licence, so you can resuse an edit it in any way you like, as long as you attribute the bits I made that you keep.

The puzzle

Four mathematicians—Ben, Katie,

Kevin, and Sam—each have one of the four clues needed to unlock a great treasure.

On a sunny/cloudy/rainy/snowy (delete as appropriate) day, they meet up in Cambridge to go punting, share their clues, work out the code for the lock,

and share out the treasure. One or more of the mathematicians, however, has decided to lie about their clue so they can steal all the treasure for themselves.

At least one mathematician is telling the truth.

(If the mathematicians say multiple sentences about their clue, then they are either all true or all false.)

They meet at Cambridge Chauffeur Punts, and head North under Silver Street Bridge.

Ben points out a plaque on the bridge with two years written on it:

"My clue," he says, "tells me that the sum of the digits of the code is equal to the sum of the digits of the earlier year on that plaque (the year is 1702). My clue also tells me that at least one of the digits of the code is 7."

The mathematicians next punt under the Mathematical Bridge, gasping in awe at its tangential trusses, then punt along the river under King's College Bridge and past King's College.

Katie points to a sign on the King's College lawn near the river:

"See that sign whose initials are PNM?" says Katie. "My clue states that first digit of the code is equal to the number of vowels on that sign (The sign says "Private: No Mooring").

My clue also tells me that at least one of the digits of the code is 1."

They then reach Clare Bridge. Kevin points out the spheres on Clare Bridge:

"My clue," he says, "states that the total number of spheres on both sides of this bridge is a factor of the code (there are 14 spheres). My clue also tells me that at least one of the digits of the code is 2."

(Kevin has not noticed that one of the spheres had a wedge missing, so counts that as a whole sphere.)

They continue past Clare College. Just before they reach Garret Hostel Bridge, Sam points out the Jerwood Library and a sign showing the year it was built (it was built in 1998):

"My clue," she says, "says that the largest prime factor of that year appears in the code (in the same way that you might say the number 18 appears in 1018 or 2189).

My clue also says that the smallest prime factor of that year appears in the code. My clue also told me that at least one of the digits of the code is 0."

They then punt under Garret Hostel Bridge, turn around between it and Trinity College Bridge, and head back towards Cambridge Chauffeur Punts.

Zut alors, the lies confuse them and they can't unlock the treasure. Can you work out who is lying and claim the treasure for yourself?

The solution

The solution to the treasure punt is given below. Once you're ready to see it, click "Show solution".

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment