Blog

2022-03-14

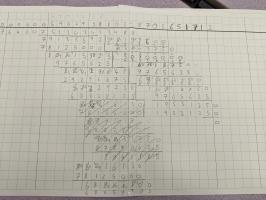

A few weekends ago, I visited Houghton-le-Spring

to spend two days helping with an attempt to compute the first 100 decimal places of π by hand. You can watch Matt Parker's video about our

calculation to find out about our method and how many correct decimal places we achieved.

Spending two days computing an approximation of π led me to wonder how accurate

calculations using various approximations of π would be.

One nice way to visualise this is to ask: what is the largest circle

whose area can be correctly computed to the nearest mm² when using a chosen approximation of π? In this

blog post, I'll answer this question for a range of approximations of π.

3

First up, how about the least accurate approximation we could possibly use: π = 3.

Using this approximation, the areas of circles with a radius of up to 1.88mm could be calculated

correctly to the nearest mm². That's a circle about the size of an ant.

Today is Pi Day, as in the date format M.DD, today's date is the first three digits of π.

Using this approximation, circles with a radius of up to 17.7mm or 1.77cm can be calculated correctly

to the nearest mm². That's a circle about the size of my thumb.

In the date format DD/M, 22 July gives an approximation of π that is more accurate than 3.14.

Using this approximation, circles with a radius of up to 19.8mm or 1.98cm can be calculated correctly

to the nearest mm². That's a slightly bigger circle that's still about the size of my thumb.

In Houghton-le-Spring, our final computed value was 3.1415926535886829815214...

The first 11 decimal places of this are correct.

Using this approximation, circles with a radius of up to \(6.71\times10^5\)mm or 671m can be calculated correctly

to the nearest mm². That's a circle about the size of Regent's park.

The 100 decimal places we were aiming for

If we'd avoided any mistakes in Hougton-le-Spring, we would've obtained the first 100 decimal places

of π. Using the first 100 decimal places of π, circles with a radius of up to \(7.8\times10^9\)mm

or 7800km can be calculated correctly

to the nearest mm². That's a circle just bigger than the Earth.

In 1873, William Shanks computed 707 decimal places of π in Houghton-le-Spring. His first 527

decimal places were correct. Using his approximation, circles with a radius of up to approximately

\(10^{263}\)mm

or \(10^{244}\) light years can be calculated correctly

to the nearest mm². The observable universe is only around \(10^{10}\) light years wide.

That's a quite big circle.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

⭐ top comment (2022-08-15) ⭐

When does "MM" give 14 for the month?Steve Spivey

I wonder if energy can be put into motion with pi, so that would be a lot of theoretical energy

Willem

Add a Comment

2019-12-27

In tonight's Royal Institution Christmas lecture,

Hannah Fry and Matt Parker demonstrated how machine learning works using MENACE.

The copy of MENACE that appeared in the lecture was build and trained by me. During the training, I logged all the moved made by MENACE and the humans playing against them, and using this data I have

created some visualisations of the machine's learning.

First up, here's a visualisation of the likelihood of MENACE choosing different moves as they play games. The thickness of each arrow represented the number of beads in the box corresponding to that move,

so thicker arrows represent more likely moves.

The likelihood that MENACE will play each move.

There's an awful lot of arrows in this diagram, so it's clearer if we just visualise a few boxes. This animation shows how the number of beads in the first box changes over time.

You can see that MENACE learnt that they should always play in the centre first, an ends up with a large number of green beads and almost none of the other colours. The following

animations show the number of beads changing in some other boxes.

MENACE learns that the top left is a good move.

MENACE learns that the middle right is a good move.

MENACE is very likely to draw from this position so learns that almost all the possible moves are good moves.

The numbers in these change less often, as they are not used in every game: they are only used when the game reached the positions shown on the boxes.

We can visualise MENACE's learning progress by plotting how the number of beads in the first box changes over time.

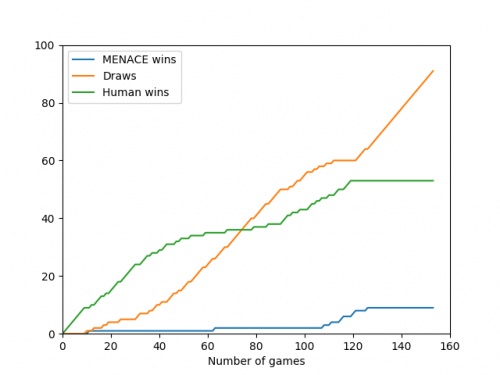

Alternatively, we could plot how the number of wins, loses and draws changes over time or view this as an animated bar chart.

The number of games MENACE wins, loses and draws.

The number of games MENACE has won, lost and drawn.

If you have any ideas for other interesting ways to present this data, let me know in the comments below.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

@(anonymous): Have you been refreshing the page? Every time you refresh it resets MENACE to before it has learnt anything.

It takes around 80 games for MENACE to learn against the perfect AI. So it could be you've not left it playing for long enough? (Try turning the speed up to watch MENACE get better.)

It takes around 80 games for MENACE to learn against the perfect AI. So it could be you've not left it playing for long enough? (Try turning the speed up to watch MENACE get better.)

Matthew

I have played around menace a bit and frankly it doesnt seem to be learning i occasionally play with it and it draws but againt the perfect ai you dont see as many draws, the perfect ai wins alot more

(anonymous)

@Colin: You can set MENACE playing against MENACE2 (MENACE that plays second) on the interactive MENACE. MENACE2's starting numbers of beads and incentives may need some tweaking to give it a chance though; I've been meaning to look into this in more detail at some point...

Matthew

Idle pondering (and something you may have covered elsewhere): what's the evolution as MENACE plays against itself? (Assuming MENACE can play both sides.)

Colin

Add a Comment

2018-07-07

So you've calculated how much you should expect the World Cup sticker book to cost

and recorded how much it actually cost. You might be wondering what else you can do with your sticker book.

If so, look no further: this post contains 5 mathematical things involvolving your sticker book and stickers.

Test the birthday paradox

In a group of 23 people, there is a more than 50% chance that two of them will share a birthday. This is often called the birthday paradox, as the number 23 is surprisingly small.

Back in 2014 when Alex Bellos suggested testing the birthday paradox on World Cup squads, as there are 23 players in a World Cup squad. I recently discovered that even further back in 2012, James Grime made a video about the birthday paradox in football games, using the players on both teams plus the referee to make 23 people.

In this year's sticker book, each player's date of birth is given above their name, so you can use your sticker book to test it out yourself.

Kaliningrad

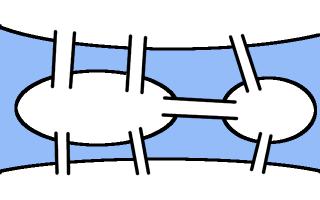

One of the cities in which games are taking place in this World Cup is Kaliningrad. Before 1945, Kaliningrad was called Königsberg. In Königsburg, there were seven bridges connecting four islands. The arrangement of these bridges is shown below.

The people of Königsburg would try to walk around the city in a route that crossed each bridge exactly one. If you've not tried this puzzle before, try to find such a route now before reading on...

In 1736, mathematician Leonhard Euler proved that it is in fact impossible to find such a route. He realised that for such a route to exist, you need to be able to pair up the bridges on each island so that you can enter the island on one of each pair and leave on the other. The islands in Königsburg all have an odd number of bridges, so there cannot be a route crossing each bridge only once.

In Kaliningrad, however, there are eight bridges: two of the original bridges were destroyed during World War II, and three more have been built. Because of this, it's now possible to walk around the city crossing each bridge exactly once.

A route around Kaliningrad crossing each bridge exactly once.

I wrote more about this puzzle, and using similar ideas to find the shortest possible route to complete a level of Pac-Man, in this blog post.

Sorting algorithms

If you didn't convince many of your friends to join you in collecting stickers, you'll have lots of swaps. You can use these to practice performing your favourite sorting algorithms.

Bubble sort

In the bubble sort, you work from left to right comparing pairs of stickers. If the stickers are in the wrong order, you swap them. After a few passes along the line of stickers, they will be in order.

In the insertion sort, you take the next sticker in the line and insert it into its correct position in the list.

In the quick sort, you pick the middle sticker of the group and put the other stickers on the correct side of it. You then repeat the process with the smaller groups of stickers you have just formed.

The football

Sticker 007 shows the official tournament ball. If you look closely (click to enlarge), you can see that the ball is made of a mixture of pentagons and hexagons. The ball is not made of only hexagons, as road signs in the UK show.

Stand up mathematician Matt Parker started a petition to get the symbol on the signs changed, but the idea was rejected.

If you have a swap of sticker 007, why not stick it to a letter to your MP about the incorrect signs as an example of what an actual football looks like.

Psychic pets

Speaking of Matt Parker, during this World Cup, he's looking for psychic pets that are able to predict World Cup results. Why not use your swaps to label two pieces of food that your pet can choose between to predict the results of the remaining matches?

Timber using my swaps to wrongly predict the first match

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

@Matthew: Thank you for the calculations. Good job I ordered the stickers I wanted #IRN. 2453 stickers - that's more than the number you bought (1781) to collect all stickers!

Milad

@Matthew: Here is how I calculated it:

You want a specific set of 20 stickers. Imagine you have already \(n\) of these. The probability that the next sticker you buy is one that you want is

$$\frac{20-n}{682}.$$

The probability that the second sticker you buy is the next new sticker is

$$\mathbb{P}(\text{next sticker is not wanted})\times\mathbb{P}(\text{sticker after next is wanted})$$

$$=\frac{662+n}{682}\times\frac{20-n}{682}.$$

Following the same method, we can see that the probability that the \(i\)th sticker you buy is the next wanted sticker is

$$\left(\frac{662+n}{682}\right)^{i-1}\times\frac{20-n}{682}.$$

Using this, we can calculate the expected number of stickers you will need to buy until you find the next wanted one:

$$\sum_{i=1}^{\infty}i \left(\frac{20-n}{682}\right) \left(\frac{662+n}{682}\right)^{i-1} = \frac{682}{20-n}$$

Therefore, to get all 682 stickers, you should expect to buy

$$\sum_{n=0}^{19}\frac{682}{20-n} = 2453 \text{ stickers}.$$

You want a specific set of 20 stickers. Imagine you have already \(n\) of these. The probability that the next sticker you buy is one that you want is

$$\frac{20-n}{682}.$$

The probability that the second sticker you buy is the next new sticker is

$$\mathbb{P}(\text{next sticker is not wanted})\times\mathbb{P}(\text{sticker after next is wanted})$$

$$=\frac{662+n}{682}\times\frac{20-n}{682}.$$

Following the same method, we can see that the probability that the \(i\)th sticker you buy is the next wanted sticker is

$$\left(\frac{662+n}{682}\right)^{i-1}\times\frac{20-n}{682}.$$

Using this, we can calculate the expected number of stickers you will need to buy until you find the next wanted one:

$$\sum_{i=1}^{\infty}i \left(\frac{20-n}{682}\right) \left(\frac{662+n}{682}\right)^{i-1} = \frac{682}{20-n}$$

Therefore, to get all 682 stickers, you should expect to buy

$$\sum_{n=0}^{19}\frac{682}{20-n} = 2453 \text{ stickers}.$$

Matthew

@Matthew: Yes, I would like to know how you work it out please. I believe I have left my email address in my comment. It seems like a lot of stickers if you are just interested in one team.

Milad

@Milad: Following a similiar method to this blog post, I reckon you'd expect to buy 2453 stickers (491 packs) to get a fixed set of 20 stickers. Drop me an email if you want me to explain how I worked this out.

Matthew

Thanks for the maths, but I have one probability question. How many packs would I have to buy, on average, to obtain a fixed set of 20 stickers?

Milad

Add a Comment

2017-11-14

A few weeks ago, I took the copy of MENACE that I built to Manchester Science Festival, where it played around 300 games against the public while learning to play Noughts and Crosses. The group of us operating MENACE for the weekend included Matt Parker, who made two videos about it. Special thanks go to Matt, plus

Katie Steckles,

Alison Clarke,

Andrew Taylor,

Ashley Frankland,

David Williams,

Paul Taylor,

Sam Headleand,

Trent Burton, and

Zoe Griffiths for helping to operate MENACE for the weekend.

As my original post about MENACE explains in more detail, MENACE is a machine built from 304 matchboxes that learns to play Noughts and Crosses. Each box displays a possible position that the machine can face and contains coloured beads that correspond to the moves it could make. At the end of each game, beads are added or removed depending on the outcome to teach MENACE to play better.

Saturday

On Saturday, MENACE was set up with 8 beads of each colour in the first move box; 3 of each colour in the second move boxes; 2 of each colour in third move boxes; and 1 of each colour in the fourth move boxes. I had only included one copy of moves that are the same due to symmetry.

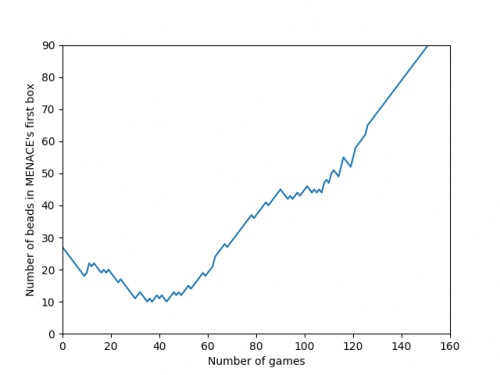

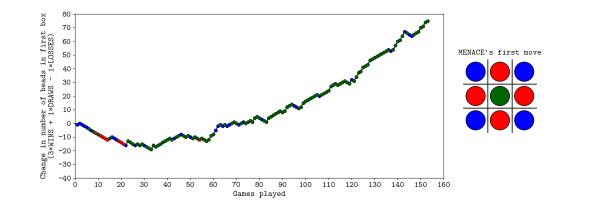

The plot below shows the number of beads in MENACE's first box as the day progressed.

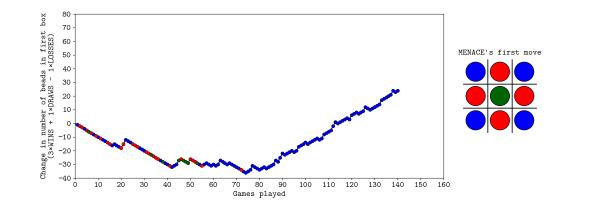

Originally, we were planning to let MENACE learn over the course of both days, but it learned more quickly than we had expected on Saturday, so we reset is on Sunday, but set it up slightly differently. On Sunday, MENACE was set up with 4 beads of each colour in the first move box; 3 of each colour in the second move boxes; 2 of each colour in third move boxes; and 1 of each colour in the fourth move boxes. This time, we left all the beads in the boxes and didn't remove any due to symmetry.

The plot below shows the number of beads in MENACE's first box as the day progressed.

You can download the full set of data that we collected over the weekend here. This includes the first two moves and outcomes of all the games over the two days, plus the number of beads in each box at the end of each day. If you do something interesting (or non-interesting) with the data, let me know!

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

WRT the comment 2017-11-17, and exactly one year later, I had the same thing happen whilst running MENACE in a 'Resign' loop for a few hours, unattended. When I returned, the orange overlay had appeared, making the screen quite difficult to read on an iPad.

g0mrb

On the JavaScript version, MENACE2 (a second version of MENACE which learns in the same way, to play against the original) keeps setting the 6th move as NaN, meaning it cannot function. Is there a fix for this?

Lambert

what would happen if you loaded the boxes slightly differently. if you started with one bead corresponding to each move in each box. if the bead caused the machine to lose you remove only that bead. if the game draws you leave the bead in play if the bead causes a win you put an extra bead in each of the boxes that led to the win. if the box becomes empty you remove the bead that lead to that result from the box before

Ian

Hi, I was playing with MENACE, and after a while the page redrew with a Dragon Curves design over the top. MENACE was still working alright but it was difficult to see what I was doing due to the overlay. I did a screen capture of it if you want to see it.

Russ

Add a Comment

2015-03-24

This is the fourth post in a series of posts about tube map folding.

A while ago, I made this (a stellated rhombicuboctahedron):

Here are some hastily typed instructions for

Matt Parker, who is making one

at this month's Maths Jam. Other people are

welcome to follow these instructions too.

You will need

- 48 tube maps

- glue

Making a module

First, take a tube map and fold the cover over. This will ensure that your

shape will have tube (map and not index) on the outside and you will have

pages to tuck your tabs between later.

Now fold one corner diagonally across to another corner. It does not matter

which diagonal you chose for the first piece but after this all following pieces

must be the same as the first.

Now fold the overlapping bit back over the top.

Turn it over and fold this overlap over too.

You have made one module.

You will need 48 of these and some glue.

Putting it together

By slotting three or four of these modules together, you can make a

pyramid with a triangle or square as its base.

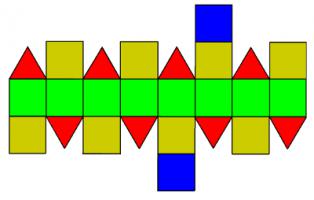

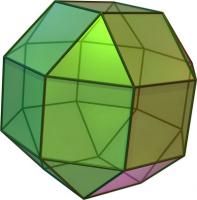

A stellated rhombicuboctahedron is a rhombicuboctahedron with a pyramid, or

stellation on each face. In other words, you now need to build a

rhombicuboctahedron with the bases of pyramids like these. A rhombicuboctahedron

looks like this:

en.wiki User Cyp, CC BY-SA 3.0

More usefully, its net looks like this:

To build a stellated rhombicuboctahedron, make this net, but with each shape

as the base of a pyramid. This is what it will look like 6/48 tube maps in:

If you make on of these, please tweet me a photo so I can see it!

Previous post in series

This is the fourth post in a series of posts about tube map folding.

Next post in series

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

I wish you'd make the final stellation of the rhombicuboctahedron! And show us! I know the shapes of the faces but have been stuck two years on the assembly!

Roberts, David

Add a Comment