Blog

2019-04-09

In the latest issue of Chalkdust,

I wrote an article

with Edmund Harriss about the Harriss spiral that appears on the cover of the magazine.

To draw a Harriss spiral, start with a rectangle whose side lengths are in the plastic ratio; that is the ratio \(1:\rho\)

where \(\rho\) is the real solution of the equation \(x^3=x+1\), approximately 1.3247179.

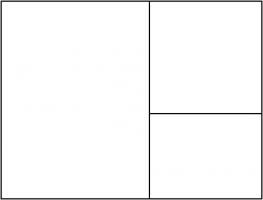

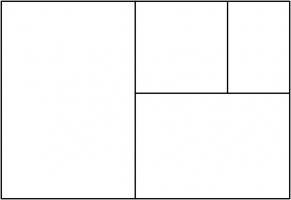

This rectangle can be split into a square and two rectangles similar to the original rectangle. These smaller rectangles can then be split up in the same manner.

Drawing two curves in each square gives the Harriss spiral.

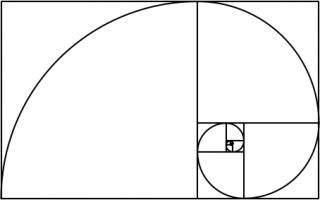

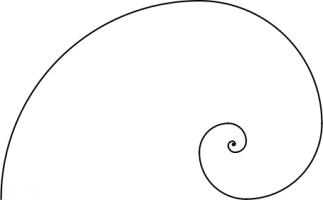

This spiral was inspired by the golden spiral, which is drawn in a rectangle whose side lengths are in the golden ratio of \(1:\phi\),

where \(\phi\) is the positive solution of the equation \(x^2=x+1\) (approximately 1.6180339). This rectangle can be split into a square and one

similar rectangle. Drawing one arc in each square gives a golden spiral.

The golden and Harriss spirals are both drawn in rectangles that can be split into a square and one or two similar rectangles.

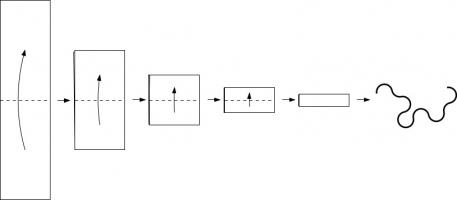

Continuing the pattern of these arrangements suggests the following rectangle, split into a square and three similar rectangles:

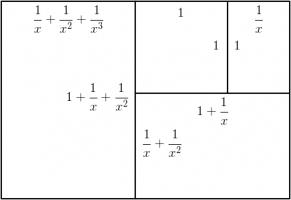

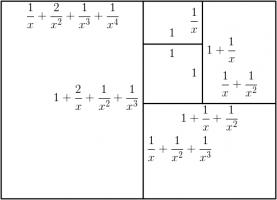

Let the side of the square be 1 unit, and let each rectangle have sides in the ratio \(1:x\). We can then calculate that the lengths of

the sides of each rectangle are as shown in the following diagram.

The side lengths of the large rectangle are \(\frac{1}{x^3}+\frac{1}{x^2}+\frac2x+1\) and \(\frac1{x^2}+\frac1x+1\). We want these to also

be in the ratio \(1:x\). Therefore the following equation must hold:

$$\frac{1}{x^3}+\frac{1}{x^2}+\frac2x+1=x\left(\frac1{x^2}+\frac1x+1\right)$$

Rearranging this gives:

$$x^4-x^2-x-1=0$$

$$(x+1)(x^3-x^2-1)=0$$

This has one positive real solution:

$$x=\frac13\left(

1

+\sqrt[3]{\tfrac12(29-3\sqrt{93})}

+\sqrt[3]{\tfrac12(29+3\sqrt{93})}

\right).$$

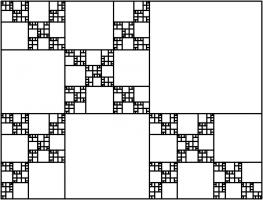

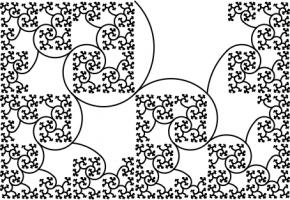

This is equal to 1.4655712... Drawing three arcs in each square allows us to make a spiral from a rectangle with sides in this ratio:

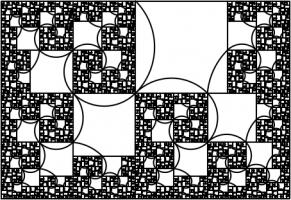

Adding a fourth rectangle leads to the following rectangle.

The side lengths of the largest rectangle are \(1+\frac2x+\frac3{x^2}+\frac1{x^3}+\frac1{x^4}\) and \(1+\frac2x+\frac1{x^2}+\frac1{x^3}\).

Looking for the largest rectangle to also be in the ratio \(1:x\) leads to the equation:

$$1+\frac2x+\frac3{x^2}+\frac1{x^3}+\frac1{x^4} = x\left(1+\frac2x+\frac1{x^2}+\frac1{x^3}\right)$$

$$x^5+x^4-x^3-2x^2-x-1 = 0$$

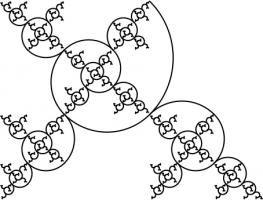

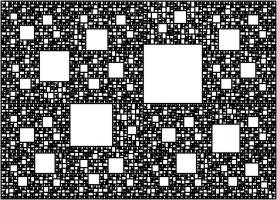

This has one real solution, 1.3910491... Although for this rectangle, it's not obvious which arcs to draw to make a

spiral (or maybe not possible to do it at all). But at least you get a pretty fractal:

We could, of course, continue the pattern by repeatedly adding more rectangles. If we do this, we get the following polynomials

and solutions:

| Number of rectangles | Polynomial | Solution |

| 1 | \(x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.618033988749895 |

| 2 | \(x^3 - x - 1=0\) | 1.324717957244746 |

| 3 | \(x^4 - x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.465571231876768 |

| 4 | \(x^5 + x^4 - x^3 - 2x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.391049107172349 |

| 5 | \(x^6 + x^5 - 2x^3 - 3x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.426608021669601 |

| 6 | \(x^7 + 2x^6 - 2x^4 - 3x^3 - 4x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.4082770325090774 |

| 7 | \(x^8 + 2x^7 + 2x^6 - 2x^5 - 5x^4 - 4x^3 - 5x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.4172584399350432 |

| 8 | \(x^9 + 3x^8 + 2x^7 - 5x^5 - 9x^4 - 5x^3 - 6x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.412713760332943 |

| 9 | \(x^{10} + 3x^9 + 5x^8 - 5x^6 - 9x^5 - 14x^4 - 6x^3 - 7x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.414969877544769 |

The numbers in this table appear to be heading towards around 1.414, or \(\sqrt2\).

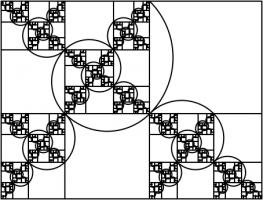

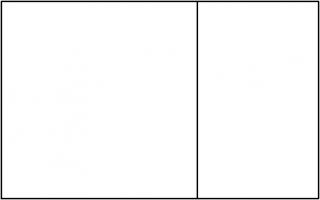

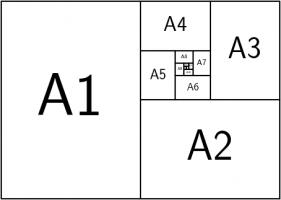

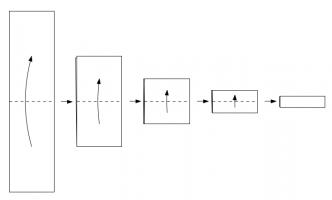

This shouldn't come as too much of a surprise because \(1:\sqrt2\) is the ratio of the sides of A\(n\) paper (for \(n=0,1,2,...\)).

A0 paper can be split up like this:

This is a way of splitting up a \(1:\sqrt{2}\) rectangle into an infinite number of similar rectangles, arranged following the pattern,

so it makes sense that the ratios converge to this.

Other patterns

In this post, we've only looked at splitting up rectangles into squares and similar rectangles following a particular pattern. Thinking about

other arrangements leads to the following question:

Given two real numbers \(a\) and \(b\), when is it possible to split an \(a:b\) rectangle into squares and \(a:b\) rectangles?

If I get anywhere with this question, I'll post it here. Feel free to post your ideas in the comments below.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

2019-05-02

@g0mrb: CORRECTION: There seems to be no way to correct the glaring error in that comment. A senior moment enabled me to reverse the nomenclature for paper sizes. Please read the suffixes as (n+1), (n+2), etc.(anonymous)

I shall remain happy in the knowledge that you have shown graphically how an A(n) sheet, which is 2 x A(n-1) rectangles, is also equal to the infinite series : A(n-1) + A(n-2) + A(n-3) + A(n-4) + ... Thank-you, and best wishes for your search for the answer to your question.

g0mrb

Add a Comment

2017-03-08

This post appeared in issue 05 of Chalkdust. I strongly

recommend reading the rest of Chalkdust.

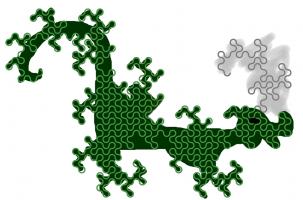

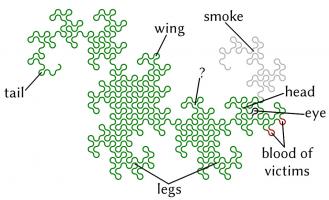

Take a long strip of paper. Fold it in half in the same direction a few times. Unfold it and look at the shape the edge of the paper

makes. If you folded the paper \(n\) times, then the edge will make an order \(n\) dragon curve, so called because it faintly resembles a

dragon. Each of the curves shown on the cover of issue 05 of Chalkdust is an order 10 dragon

curve.

Top: Folding a strip of paper in half four times leads to an order four dragon curve (after rounding the corners). Bottom: A level 10 dragon curve resembling a dragon.

The dragon curves on the cover show that it is possible to tile the entire plane with copies of dragon curves of the same order. If any

readers are looking for an excellent way to tile a bathroom, I recommend getting some dragon curve-shaped tiles made.

An order \(n\) dragon curve can be made by joining two order \(n-1\) dragon curves with a 90° angle between their tails. Therefore, by

taking the cover's tiling of the plane with order 10 dragon curves, we may join them into pairs to get a tiling with order 11 dragon

curves. We could repeat this to get tilings with order 12, 13, and so on... If we were to repeat this ad infinitum we would arrive

at the conclusion that an order \(\infty\) dragon curve will cover the entire plane without crossing itself. In other words, an order

\(\infty\) dragon curve is a space-filling curve.

Like so many other interesting bits of recreational maths, dragon curves were popularised by Martin Gardner in one of his Mathematical Games columns in Scientific

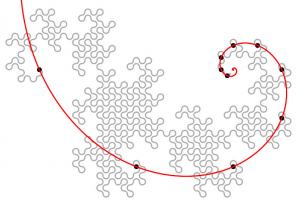

American. In this column, it was noted that the endpoints of dragon curves of different orders (all starting at the same point) lie on

a logarithmic spiral. This can be seen in the diagram below.

Although many of their properties have been known for a long time and are well studied, dragon curves continue to appear in new and

interesting places. At last year's Maths Jam conference, Paul Taylor gave a talk about my favourite surprise occurrence of

a dragon.

Normally when we write numbers, we write them in base ten, with the digits in the number representing (from right to left) ones, tens,

hundreds, thousands, etc. Many readers will be familiar with binary numbers (base two), where the powers of two are used in the place of

powers of ten, so the digits represent ones, twos, fours, eights, etc.

In his talk, Paul suggested looking at numbers in base -1+i (where i is the square root of -1; you can find more adventures of i here) using the digits 0 and 1. From right to left, the columns of numbers in this

base have values 1, -1+i, -2i, 2+2i, -4, etc. The first 11 numbers in this base are shown below.

| Number in base -1+i | Complex number |

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 |

| 10 | -1+i |

| 11 | (-1+i)+(1)=i |

| 100 | -2i |

| 101 | (-2i)+(1)=1-2i |

| 110 | (-2i)+(-1+i)=-1-i |

| 111 | (-2i)+(-1+i)+(1)=-i |

| 1000 | 2+2i |

| 1001 | (2+2i)+(1)=3+2i |

| 1010 | (2+2i)+(-1+i)=1+3i |

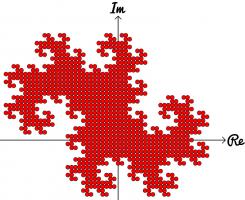

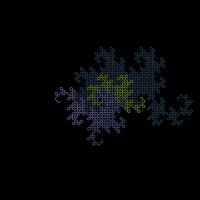

Complex numbers are often drawn on an Argand diagram: the real part of the number is plotted on the horizontal axis and the imaginary part

on the vertical axis. The diagram to the left shows the numbers of ten digits or less in base -1+i on an Argand diagram. The points form

an order 10 dragon curve! In fact, plotting numbers of \(n\) digits or less will draw an order \(n\) dragon curve.

Brilliantly, we may now use known properties of dragon curves to discover properties of base -1+i. A level \(\infty\) dragon curve covers

the entire plane without intersecting itself: therefore every Gaussian integer (a number of the form \(a+\text{i} b\) where \(a\) and

\(b\) are integers) has a unique representation in base -1+i. The endpoints of dragon curves lie on a logarithmic spiral: therefore

numbers of the form \((-1+\text{i})^n\), where \(n\) is an integer, lie on a logarithmic spiral in the complex plane.

If you'd like to play with some dragon curves, you can download the Python code used

to make the pictures here.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment

2016-03-30

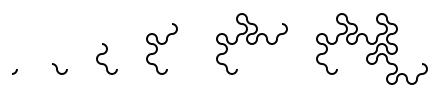

Take a piece of paper. Fold it in half in the same direction many times. Now unfold it. What pattern will the folds make?

I first found this question in one of Martin Gardner's books. At first, you might that the answer will be simple, but if you look at the shapes made for a few folds, you will see otherwise:

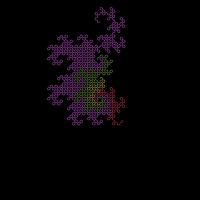

The curves formed are called dragon curves as they allegedly look like dragons with smoke rising from their nostrils. I'm not sure I see the resemblance:

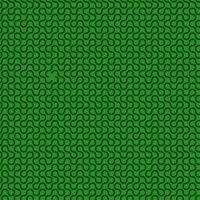

As you increase the order of the curve (the number of times the paper was folded), the dragon curve squiggles across more of the plane, while never crossing itself. In fact, if the process was continued forever, an order infinity dragon curve would cover the whole plane, never crossing itself.

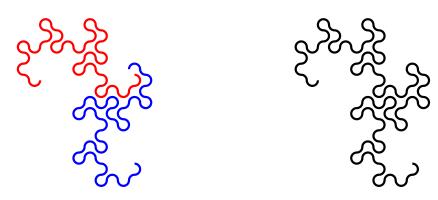

This is not the only way to cover a plane with dragon curves: the curves tessellate.

When tiled, this picture demonstrates how dragon curves tessellate. For a demonstration, try obtaining infinite lives...

Dragon curves of different orders can also fit together:

To generate digital dragon curves, first notice that an order \(n\) curve can be made from two order \(n-1\) curves:

This can easily be seen to be true if you consider folding paper: If you fold a strip of paper in half once, then \(n-1\) times, each half of the strip will have made an order \(n-1\) dragon curve. But the whole strip has been folded \(n\) times, so is an order \(n\) dragon curve.

Because of this, higher order dragons can be thought of as lots of lower order dragons tiled together. An the infinite dragon curve is actually equivalent to tiling the plane with a infinite number of dragons.

If you would like to create your own dragon curves, you can download the Python code I used to draw them from GitHub. If you are more of a thinker, then you might like to ponder what difference it would make if the folds used to make the dragon were in different directions.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment