Blog

2022-03-14

A few weekends ago, I visited Houghton-le-Spring

to spend two days helping with an attempt to compute the first 100 decimal places of π by hand. You can watch Matt Parker's video about our

calculation to find out about our method and how many correct decimal places we achieved.

Spending two days computing an approximation of π led me to wonder how accurate

calculations using various approximations of π would be.

One nice way to visualise this is to ask: what is the largest circle

whose area can be correctly computed to the nearest mm² when using a chosen approximation of π? In this

blog post, I'll answer this question for a range of approximations of π.

3

First up, how about the least accurate approximation we could possibly use: π = 3.

Using this approximation, the areas of circles with a radius of up to 1.88mm could be calculated

correctly to the nearest mm². That's a circle about the size of an ant.

Today is Pi Day, as in the date format M.DD, today's date is the first three digits of π.

Using this approximation, circles with a radius of up to 17.7mm or 1.77cm can be calculated correctly

to the nearest mm². That's a circle about the size of my thumb.

In the date format DD/M, 22 July gives an approximation of π that is more accurate than 3.14.

Using this approximation, circles with a radius of up to 19.8mm or 1.98cm can be calculated correctly

to the nearest mm². That's a slightly bigger circle that's still about the size of my thumb.

In Houghton-le-Spring, our final computed value was 3.1415926535886829815214...

The first 11 decimal places of this are correct.

Using this approximation, circles with a radius of up to \(6.71\times10^5\)mm or 671m can be calculated correctly

to the nearest mm². That's a circle about the size of Regent's park.

The 100 decimal places we were aiming for

If we'd avoided any mistakes in Hougton-le-Spring, we would've obtained the first 100 decimal places

of π. Using the first 100 decimal places of π, circles with a radius of up to \(7.8\times10^9\)mm

or 7800km can be calculated correctly

to the nearest mm². That's a circle just bigger than the Earth.

In 1873, William Shanks computed 707 decimal places of π in Houghton-le-Spring. His first 527

decimal places were correct. Using his approximation, circles with a radius of up to approximately

\(10^{263}\)mm

or \(10^{244}\) light years can be calculated correctly

to the nearest mm². The observable universe is only around \(10^{10}\) light years wide.

That's a quite big circle.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

⭐ top comment (2022-08-15) ⭐

When does "MM" give 14 for the month?Steve Spivey

I wonder if energy can be put into motion with pi, so that would be a lot of theoretical energy

Willem

Add a Comment

2018-09-13

This is a post I wrote for round 2 of The Aperiodical's Big Internet Math-Off 2018. As I went out in round 1 of the Big Math-Off, you got to read about the real projective plane instead of this.

Polynomials are very nice functions: they're easy to integrate and differentiate, it's quick to calculate their value at points, and they're generally friendly to deal with. Because of this, it can often be useful to find a polynomial that closely approximates a more complicated function.

Imagine a function defined for \(x\) between -1 and 1. Pick \(n-1\) points that lie on the function. There is a unique degree \(n\) polynomial (a polynomial whose highest power of \(x\) is \(x^n\)) that passes through these points. This polynomial is called an interpolating polynomial, and it sounds like it ought to be a pretty good approximation of the function.

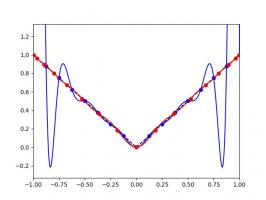

So let's try taking points on a function at equally spaced values of \(x\), and try to approximate the function:

$$f(x)=\frac1{1+25x^2}$$

I'm sure you'll agree that these approximations are pretty terrible, and they get worse as more points are added. The high error towards 1 and -1 is called Runge's phenomenon, and was discovered in 1901 by Carl David Tolmé Runge.

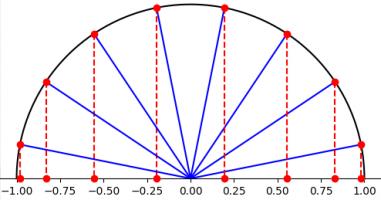

All hope of finding a good polynomial approximation is not lost, however: by choosing the points more carefully, it's possible to avoid Runge's phenomenon. Chebyshev points (named after Pafnuty Chebyshev) are defined by taking the \(x\) co-ordinate of equally spaced points on a circle.

The following GIF shows interpolating polynomials of the same function as before using Chebyshev points.

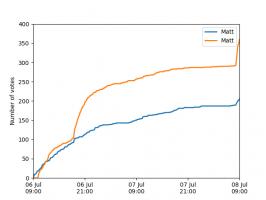

Nice, we've found a polynomial that closely approximates the function... But I guess you're now wondering how well the Chebyshev interpolation will approximate other functions. To find out, let's try it out on the votes over time of my first round Big Internet Math-Off match.

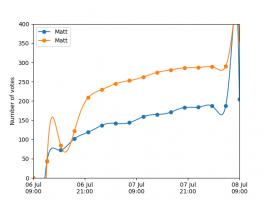

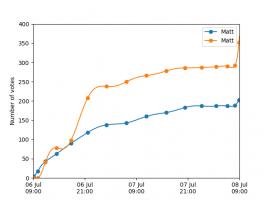

The graphs below show the results of the match over time interpolated using 16 uniform points (left) and 16 Chebyshev points (right). You can see that the uniform interpolation is all over the place, but the Chebyshev interpolation is very close the the actual results.

Scroggs vs Parker, 6-8 July 2018, approximated using uniform points (left) and Chebyshev points (right)

But maybe you still want to see how good Chebyshev interpolation is for a function of your choice... To help you find out, I've wrote @RungeBot, a Twitter bot that can compare interpolations with equispaced and Chebyshev points.

Since first publishing this post, Twitter's API changes broke @RungeBot, but it lives on on Mathstodon: @RungeBot@mathstodon.xyz.

Just tweet it a function, and it'll show you how bad Runge's phenomenon is for that function, and how much better Chebysheb points are.

For example, if you were to toot "@RungeBot@mathstodon.xyz f(x)=abs(x)", then RungeBot would reply: "Here's your function interpolated using 17 equally spaced points (blue) and 17 Chebyshev points (red). For your function, Runge's phenomenon is terrible."

A list of constants and functions that RungeBot understands can be found here.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Hi Matthew, I really like your post. Is there a benefit of using chebyshev spaced polynomial interpolation rather than OLS polynomial regression when it comes to real world data? It is clear to me, that if you have a symmetric function your approach is superior in capturing the center data point. But in my understanding in your vote-example a regression minimizing the residuals would be preferrable in minimizing the error. Or do I miss something?

Benedikt

Add a Comment