Blog

2016-12-23

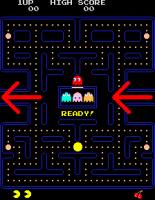

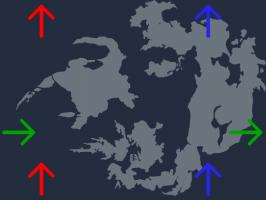

In many early arcade games, the size of the playable area was limited by the size of the screen. To make this area seem larger, or to

make gameplay more interesting, many games used wraparound; allowing the player to leave one side of the screen and return on another.

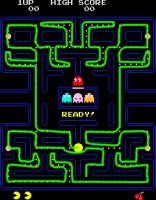

In Pac-Man, for example, the player could leave the left of the screen along the arrow shown and return

on the right, or vice versa.

Pac-Man's apparent teleportation from one side of the screen to the other may seem like magic, but it is more easily explained by

the shape of Pac-Man's world being a cylinder.

Rather than jumping or teleporting from one side to the other, Pac-Man simply travels round the cylinder.

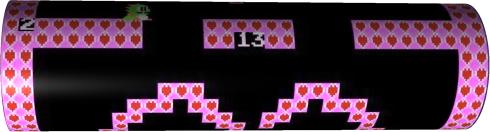

Bubble Bobble was first released in 1986 and features two dragons, Bub and Bob, who are tasked with

rescuing their girlfriends by trapping 100 levels

worth of monsters inside bubbles. In these levels, the dragons and monsters may leave the bottom of the screen to return at the top.

Just like in Pac-Man, Bub and Bob live on the surface of a cylinder, but this time it's horizontal not vertical.

A very large number of arcade games use left-right or top-bottom wrapping and have the same cylindrical shape as Pac-Man or Bubble Bobble.

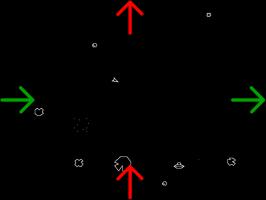

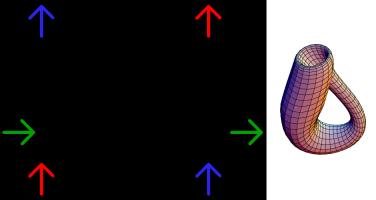

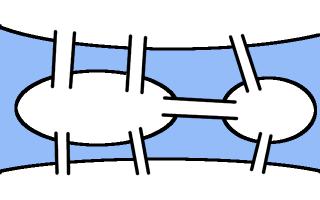

In Asteroids, both left-right and top-bottom wrapping are used.

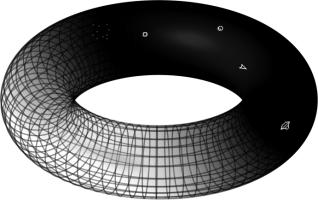

The ships and asteroids in Asteroids live on the surface of a torus, or doughnut: a cylinder around to make its two ends meet up.

There is, however, a problem with the torus show here. In Asteroids, the ship will take amount of time to get from the left of the screen

to the right however high or low on the screen it is. But the ship can get around the inside of the torus shown faster than it can

around the outside, as the inside is shorter. This is because the screen of play is completely flat, while the inside and outside halves of

the torus are curved.

It is impossible to make a flat torus in three-dimensional space, but it is possible to make one in

four-dimensional space.

Therefore, while Asteroids seems to be a simple two-dimensional game, it is actually taking place on a four-dimensional surface.

Wrapping doesn't only appear in arcade games. Many games in the excellent Final Fantasy series use wrapping on the world maps, as shown here

on the Final Fantasy VIII map.

Just like in Asteroids, this wrapping means that Squall & co. carry out their adventure on the surface of a four-dimensional flat torus.

The game designers, however, seem to not have realised this, as shown in this screenshot including a spherical (!) map.

Due to the curvature of a sphere, lines that start off parallel eventually meet. This makes it impossible to map

nicely between a flat surface to a sphere (this is why so many different map projections exist), and heavily complicates the task of making

a game with a truly spherical map. So I'll let the Final Fantasy VIII game designers off. Especially since the rest of the game is such

incredible fun.

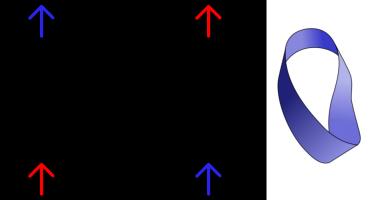

It is sad, however, that there are no games (at leat that I know of) that make use of the great variety of different wrapping rules available. By only

slightly adjusting the wrapping rules used in the games in this post, it is possible to make games on a variety of other surfaces,

such a Klein bottles or Möbius strips as shown below.

If you know of any games make use of these surfaces, let me know in the comments below!

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

⭐ top comment (2022-05-28) ⭐

Thanks for postOliver

HyperRogue also has special modes which experiment with other geometries (spherical, and elliptic which is non-orientable). Hydra Slayer has Mobius strip and Klein bottle levels.

Zeno Rogue

HyperRogue is an example of a game that takes place on the hyperbolic plane. Rather than looping, the map is infinite.

See: http://zenorogue.blogspot.com.au/2012/...

See: http://zenorogue.blogspot.com.au/2012/...

maetl

Hyperrogue may be the only game in existence with a hyperbolic surface topology: http://www.roguetemple.com/z/hyper/

zaratustra

F-Zero GX had a track called Mobius Ring, that was... well, a Möbius ring.

F-Zero X had a more trivial track that was just the outward side of a regular ring, but it was rather weird too, because it meant that this was a looping track that had no turns.

F-Zero X had a more trivial track that was just the outward side of a regular ring, but it was rather weird too, because it meant that this was a looping track that had no turns.

Olaf

Add a Comment

2015-03-25

This is an article which I wrote for the

first issue of

Chalkdust. I highly recommend reading the rest of the magazine (and trying

to solve the crossnumber I wrote for the issue).

In the classic arcade game Pac-Man, the player moves the title character through a maze. The aim of

the game is to eat all of the pac-dots that are spread throughout the maze while avoiding the ghosts

that prowl it.

While playing Pac-Man recently, my concentration drifted from the pac-dots and I began to think

about the best route I could take to complete the level.

Seven bridges of Königsberg

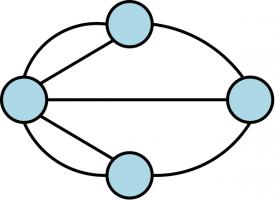

In the 1700s, Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler studied a related problem. The city of

Königsberg had seven bridges, which the residents would try to cross while walking around the

town. However, they were unable to find a route crossing every bridge without repeating one of them.

Diagram showing the bridges in Königsberg. If you have not

seen this puzzle before, you may like to try to find a route crossing them all exactly once before reading on.

In fact, the city dwellers could not find such a route because it is impossible to do so, as

Euler proved in 1735. He first simplified the map of the city, by making the islands into vertices (or nodes)

and the bridges into edges.

This type of diagram has (slightly confusingly) become known as a graph, the study of which is

called graph theory. Euler represented Königsberg in this way as he realised that the shape of the

islands is irrelevant to the problem: representing the problem as a graph gets rid of this useless information

while keeping the important details of how the islands are connected.

Euler next noticed that if a route crossing all the bridges exactly once was possible then whenever

the walker took a bridge onto an island, they must take another bridge off the island. In this way,

the ends of the bridges at each island can be paired off. The only bridge ends that do not need a

pair are those at the start and end of the circuit.

This means that all of the vertices of the graph except two (the first and last in the route) must have an even number of edges connected to them; otherwise there is no route around the graph

travelling along each edge exactly once. In Königsberg, each island is connected to an odd number of bridges. Therefore the route that

the residents were looking for did not exist (a route now exists due to two of the bridges being destroyed during World War II).

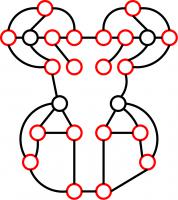

This same idea can be applied to Pac-Man. By ignoring the parts of the maze without pac-dots the pac-graph

can be created, with the paths and the junctions forming the edges and vertices respectively. Once this

is done there will be twenty-four vertices, twenty of which will be connected to an odd number of edges, and so it is impossible to eat

all of the pac-dots without repeating some edges or travelling along parts of the maze with no pac-dots.

This is a start, but it does not give us the shortest route we can take to eat all of the pac-dots: in

order to do this, we are going to have to look at the odd vertices in more detail.

The Chinese postman problem

The task of finding the shortest route covering all the edges of a graph has become known as the

Chinese postman problem as it is faced by postmen—they need to walk along each street to post

letters and want to minimise the time spent walking along roads twice—and it was first studied by

Chinese mathematician Kwan Mei-Ko.

As the seven bridges of Königsberg problem demonstrated, when trying to find a route, Pac-Man

will get stuck at the odd vertices. To prevent this from happening, all the vertices can be made into even

vertices by adding edges to the graph. Adding an edge to the graph corresponds to choosing an edge, or sequence

of edges, for Pac-Man to repeat or including a part of the maze without pac-dots. In order to complete the level

with the shortest distance travelled, Pac-Man wants to add the shortest total length of edges to the graph.

Therefore, in order to find the best route, Pac-Man must look at different ways to pair off the odd vertices and choose

the pairing which will add the least total distance to the graph.

The Chinese postman problem and the Pac-Man problem are slightly different: it is usually assumed

that the postman wants to finish where he started so he can return home. Pac-Man however can finish

the level wherever he likes but his starting point is fixed. Pac-Man may therefore leave one odd

node unpaired but must add an edge to make the starting node odd.

One way to find the required route is to look at all possible ways to pair up the odd vertices. With a low

number of odd vertices this method works fine, but as the number of odd vertices increases, the

method quickly becomes slower.

With four odd vertices, there are three possible pairings. For the Pac-Man problem there will be

over 13 billion (\(1.37\times 10^{10}\)) pairings to check. These pairings can be checked by a

laptop running overnight, but for not too many more vertices this method quickly becomes unfeasible.

With 46 odd nodes there will be more than one pairing per atom in the human body (\(2.53\times 10^{28}\)).

By 110 odd vertices there will be more pairings (\(3.47\times 10^{88}\)) than there are estimated to be atoms in the

universe. Even the greatest supercomputer will be unable to work its way through

all these combinations.

Better algorithms are known for this problem that reduce the amount of work on larger graphs. The number of

pairings to check in the method above increases like the factorial of the number of vertices. Algorithms are

known for which the amount of work to be done increases like a polynomial in the number of vertices. These algorithms

will become unfeasible at a much slower rate but will still be unable to deal with very large graphs.

Solution of the Pac-Man problem

For the Pac-Man problem, the shortest pairing of the odd vertices requires the edges marked in red to be

repeated. Any route which repeats these edges will be optimal. For example, the route in green will be

optimal.

One important element of the Pac-Man gameplay that I have neglected are the ghosts (Blinky, Pinky,

Inky and Clyde), which Pac-Man must avoid. There is a high chance that the ghosts will at some point

block the route shown above and ruin Pac-Man's optimality. However, any route repeating the red edges

will be optimal: at many junctions Pac-Man will have a choice of edges he could continue along. It may

be possible for a quick thinking player to utilise this freedom to avoid the ghosts and complete an optimal

game.

Additionally, the skilled player may choose when to take the edges that include the power pellets,

which allow Pac-Man to reverse the roles and eat the ghosts. Again cleverly timing these may allow

the player to complete an optimal route.

Unfortunately, as soon as the optimal route is completed, Pac-Man moves to the next level and the

player has to do it all over again ad infinitum.

A video

Since writing this piece, I have been playing Pac-Man using

MAME (Multiple Arcade Machine Emulator). Here is one game I played along

with the optimal edges to repeat for reference:

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

@William: You're right. In a number of places I could've turned round a few pixels earlier.

There seems to be no world record for just one Pac-Man level (and I don't have time to get good enough to speed run all 255 levels before it crashes!)

There seems to be no world record for just one Pac-Man level (and I don't have time to get good enough to speed run all 255 levels before it crashes!)

Matthew

This vid was billed as an "optimal" run but around 40 seconds in you eat one "pill" that you don't need to eat. Why don't you just speedrun the first level? This must have been done before. Can you beat the world record?

William

Add a Comment