Blog

2016-06-05

The Game of Life is a cellular automaton invented by John Conway in 1970,

and popularised by Martin Gardner.

In Life, cells on a square grid are either alive or dead. It begins

at generation 0 with some cells alive and some dead. The cells' aliveness in

the following generations are defined by the following rules:

- Any live cell with four or more live neighbours dies of overcrowding.

- Any live cell with one or fewer live neighbours dies of loneliness.

- Any dead cell with exactly three live neighbours comes to life.

Starting positions can be found which lead to all kinds of behaviour:

from making gliders

to generating prime numbers.

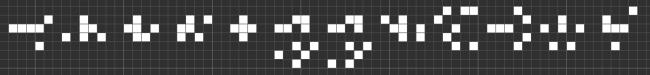

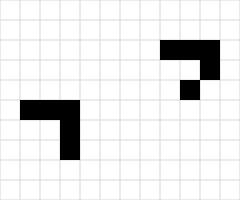

The following starting position is one of my favourites:

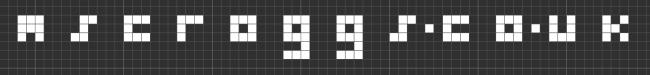

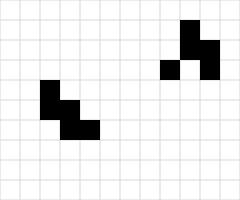

It looks boring enough, but in the next generation, it will look like this:

If you want to confirm that I'm not lying, I recommend the free Game of Life Software Golly.

Going backwards

You may be wondering how I designed the starting pattern above. A first, it looks like a difficult task: each cell can be dead or alive,

so I need to check every possible combination until I find one. The number of combinations will be \(2^\text{number of cells}\). This will

be a very large number.

There are simplifications that can be made, however. Each of the letters above (ignoring the gs) is in a 3×3 block, surrounded

by dead cells. Only the cells in the 5×5 block around this can affect the letter. These 5×5 blocks do no overlap, so can be

calculated seperately. I doesn't take too long to try all the possibilities for these 5×5 blocks. The gs were then made by starting with an o and trying adding cells below.

Can I make my name?

Yes, you can make your name.

I continued the search and found a 5×5 block for each letter. Simply Enter your name in the box below and

these will be combined to make a pattern leading to your name!

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment

2016-03-15

This article first appeared in

issue 03 of

Chalkdust. I highly recommend reading the rest of the magazine (and trying

to solve the crossnumber I wrote for the issue).

It all began in December 1956, when an article about hexaflexagons was published in Scientific American. A hexaflexagon is a

hexagonal paper toy which can be folded and then opened out to reveal hidden faces. If you have never made a hexaflexagon, then you should stop

reading and make one right now. Once you've done so, you will understand why the article led to a craze in New York;

you will probably even create your own mini-craze because you will just need to show it to everyone you know.

The author of the article was, of course, Martin Gardner.

Martin Gardner was born in 1914 and grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He earned a bachelor's degree in philosophy from the University of Chicago and

after four years serving in the US Navy during the Second World War, he returned to Chicago and began writing. After a few years working on

children's magazines and the occasional article for adults, Gardner was introduced to John Tukey, one of the students who had been involved in

the creation of hexaflexagons.

Soon after the impact of the hexaflexagons article became clear, Gardner was asked if he had enough material to maintain a monthly column.

This column, Mathematical Games, was written by Gardner every month from January 1956 for 26 years until December 1981. Throughout its run,

the column introduced the world to a great number of mathematical ideas, including Penrose tiling, the Game of Life, public key encryption,

the art of MC Escher, polyominoes and a matchbox machine learning robot called MENACE.

Life

Gardner regularly received topics for the column directly from their inventors. His collaborators included Roger Penrose, Raymond Smullyan,

Douglas Hofstadter, John Conway and many, many others. His closeness to researchers allowed him to write about ideas that

the general public were previously unaware of and share newly researched ideas with the world.

In 1970, for example, John Conway invented the Game of Life, often simply referred to as Life. A few weeks later, Conway showed the game to Gardner, allowing

him to write the first ever article about the now-popular game.

In Life, cells on a square lattice are either alive (black) or dead (white). The status of the cells in the next generation of the game is given by the following

three rules:

- Any live cell with one or no live neighbours dies of loneliness;

- Any live cell with four or more live neighbours dies of overcrowding;

- Any dead cell with exactly three live neighbours becomes alive.

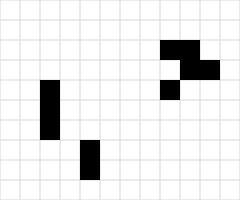

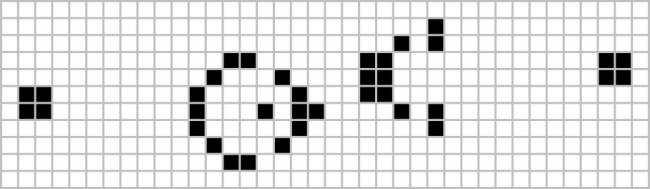

For example, here is a starting configuration and its next two generations:

The collection of blocks on the right of this game is called a glider, as it will glide to the right and upwards as the generations advance.

If we start Life with a single glider, then the glider will glide across the board forever, always covering five squares: this starting position

will not lead to the sad ending where everything is dead. It is not obvious, however, whether there is a starting

configuration that will lead the number of occupied squares to increase without bound.

Originally, Conway and Gardner thought that this was impossible, but after the article was published, a reader and mathematician called Bill Gosper

discovered the glider gun: a starting arrangement in Life that fires a glider every 30 generations. As each of these gliders will go on to live

forever, this starting configuration results in the number of live cells

perpetually increasing!

This discovery allowed Conway to prove that any Turing machine can be built within Life: starting

arrangements exist that can calculate the digits of pi, solve equations, or do any other calculation a computer is capable of (although very slowly)!

Encrypting with RSA

To encode the message \(809\), we will use the public key:

$$s=19\quad\text{and}\quad r=1769$$

The encoded message is the remainder when the message to the power of \(s\) is divided by \(r$:

$$809^{19}\equiv\mathbf{388}\mod1769$$

Decrypting with RSA

To decode the message, we need the two prime factors of \(r\) (\(29\) and \(61\)).

We multiply one less than each of these together:

\begin{align*}

a&=(29-1)\times(61-1)\\[-2pt]

&=1680.

\end{align*}

We now need to find a number \(t\) such that \(st\equiv1\mod a\). Or in other words:

$$19t\equiv1\mod 1680$$

One solution of this equation is \(t=619\) (calculated via the extended Euclidean algorithm).

Then we calculate the remainder when the encoded message to the power of \(t\) is divided by \(r\):

$$388^{619}\equiv\mathbf{809}\mod1769$$

RSA

Another concept that made it into Mathematical Games shortly after its discovery was public key cryptography. In mid-1977, mathematicians Ron

Rivest, Adi Shamir and Leonard Adleman invented the method of encryption now known as RSA (the initials of their surnames). Here,

messages are encoded using two publicly shared numbers, or keys. These numbers and the method used to encrypt messages can be publicly shared as

knowing this information does not reveal how to decrypt the message. Rather, decryption of the message requires knowing the prime factors of one of the keys. If this key is the product of two very large

prime numbers, then this is a very difficult task.

Something to think about

Gardner had no education in maths beyond high school, and at times had difficulty understanding the material he was writing about. He believed, however, that this was a strength and not a weakness: his struggle to understand led him to write in a way that other non-mathematicians could follow. This goes a long way to explaining the popularity of his column.

After Gardner finished working on the column, it was continued by Douglas Hofstadter and then AK Dewney before being passed down to Ian Stewart.

Gardner died in May 2010, leaving behind hundreds of books and articles. There could be no better way to end than with something for you to go

away and think about. These of course all come from Martin Gardner's Mathematical Games:

- Find a number base other than 10 in which 121 is a perfect square.

- Why do mirrors reverse left and right, but not up and down?

- Every square of a 5-by-5 chessboard is occupied by a knight.

- Is it possible for all 25 knights to move simultaneously in such a way that at the finish all cells are still occupied as before?

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment