Blog

2025-03-17

This is an article which I wrote for

Chalkdust issue 21.

For ten years now, I've been setting the Chalkdust crossnumber. Over this time, I've developed a lot of tricks and tools for setting good puzzles.

Although puzzles involving words in grids of squares have been around since at least the 1800s, the first crossword (or word-cross as the author called it) puzzle was published in the New York World newspaper in 1913. Since this, crosswords have become a staple in newspapers and magazines around the world.

In the UK, cryptic crosswords were invented and grew in popularity in the 1900s and now appear in most newspapers and magazines. The cryptic crossword in the Listener magazine became infamous as the hardest such puzzle. the Listener ceased publication in 1991, but the Listener crossword still lives on and is now published on Saturdays in the Times newspaper.

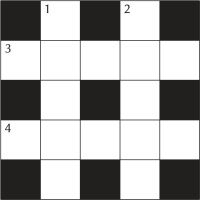

In early 2015, we were discussing ideas for regular content in our brand new maths magazine, and wanted to include a more mathematical crossword-style puzzle. Like Venus emerging from the shell, the crossnumber was born.

Of course, we didn't invent the crossnumber puzzle: the first known crossnumber puzzle was written by Henry Dudeney and published by Strand Magazine in 1926; four times a year, the Listener features a numerical puzzle; and the UKMT (United Kingdom Mathematics Trust) have included a crossnumber as part of their team challenge for many years. There are also plenty of other publications that include crossnumbers, including the very enjoyable Crossnumbers Quarterly, that's been publishing collections of the puzzles four times a year since 2016. But perhaps we'll be mentioned in a footnote in a book about the history of puzzles.

But anyway, we'd decided we needed a crossnumber, so I needed to write one...

Making a grid

The first step when creating a puzzle is to create the grid. Like many publications, we restrict ourselves to using grids of squares (for the main crossnumber at least---we allow more freedom in other puzzles that we feature).

Typically, a publication will impose some restrictions on the placement of the black squares in its puzzle. The most popular restrictions are:

- The white squares must be simply connected (for any two white squares, it is possible to draw a path between them that only goes through white squares);

- The arrangement of black squares must be in some way symmetric;

- The proportion of squares that are black cannot be too high.

There are two forms of symmetry that are used in crossword grids: rotational symmetry and reflectional symmetry. Both order 2 (rotate the grid 180° and it looks the same) and order 4 (rotate the grid 90° and it looks the same) rotational symmetry are commonly used in crossword grids, with order 2 rotational symmetry often being the minimal allowable amount of symmetry. You'll want to be careful when making a grid with order 4 rotational symmetry, as it's very easy to make your grid into an accidental swastika.

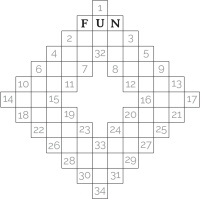

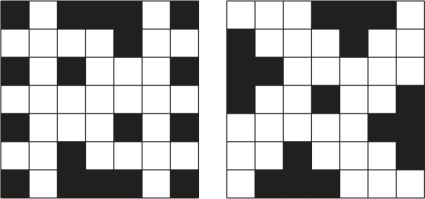

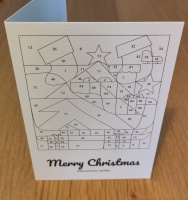

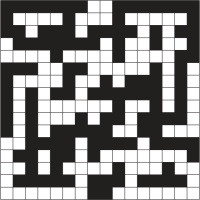

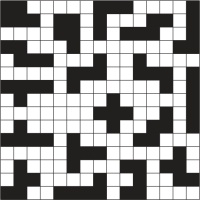

With a few notable exceptions, the grids for the Chalkdust crossnumber have some form of symmetry, and also follow the other two restrictions. We do, however, allow some flexibility on these restrictions if it allows us to use an interesting grid. For crossnumber #14 (shown on the left), we experimented with translational symmetry, leading to a grid that was not simply connected and with a greater than usual proportion of black squares. For crossnumbers #11 and #6, the grids had a nice property: rotating the grid leads to the same pattern of squares with the colours inverted. Once again we had to break the requirements on connectedness and the proportion of black squares to do this.

The grid for crossnumber #11. Rotating this grid 90° leads to the same grid with inverted colours. This grid also has order 2 rotational symmetry.

The grid for crossnumber #6. Rotating this grid 180° leads to the same grid with inverted colours.

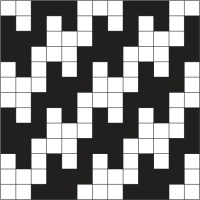

The grid for crossnumber #17 was not symmetric, and instead included all 18 pentominoes in black.

For crossnumber #17, we skipped imposing symmetry entirely and instead formed all 18 pentominoes from the black squares in the grid. This really pleased me, as there were clues in the puzzle related to the number of pentominoes and the number of black squares in the grid.

For American style crosswords, there's an additional restriction that is imposed: all white squares must be checked. A white square is called 'checked' if it is part of an across entry and a down entry---and so you can fill that square in by solving one of two different clues. Due to this, American crosswords will have large rectangles composed entirely of white squares and never have lines of alternating black and white squares as commonly seen in British puzzles.

When writing a crossword, it is common to pick the words to include while making the grid, as trying to find valid words or phrases to fill a predetermined grid is a challenging task. (Thankfully, there's software out there that can help you make grids from a list of words.) For crossnumbers, filling the grid is a much easier task as any string of digits not starting with a zero is a valid entry. This ease of filling the grid is what allowed us to use the interesting restriction-breaking grids mentioned in this section.

For crosswords, it is also common to disallow the use of two-letter words. For the crossnumber, removing two-digit numbers would remove the potential for a lot of fun number puzzles, so we don't impose this restriction here. We allow two-letter words in the Chalkdust cryptic too, as they can be really useful when trying to make a grid with our additional restriction that the majority of the included words should be related to maths.

Setting the clues

Once I've made the grid for a crossnumber, the next task is to write the clues.

Often, I start this task by picking a fun mathematical or logic puzzle to include in the clues. Sometimes, this is a single clue, such as this one from crossnumber #1:

Down

6. This number's first digit tells you how many 0s are in this number, the second digit how many 1s, the third digit how many 2s, and so on. (10)

Or this clue from crossnumber #5:

Across

9. A number \(a\) such that the equation \(3x^2+ax+75\) has a repeated root. (2)

Other times, this could be a set of clues that refer to each other and reveal enough information to work out what one of the entries should be, such as these clues from crossnumber #10:

Across

13. 49A reversed. (3)

37. The difference between 49A and 13A. (3)

47. 37A reversed. (3)

48. The sum of 47A and 37A. (4)

49. Each digit of this number (except the first) is (strictly) less than the previous digit. (3)

Once I've included a few sets of clues like this, it's time to write the rest of the clues. As any crossnumber solvers will have noticed, my favourite type of clue to add from this point on is a clue that refers to another entry.

More recently, I've begun adding an additional mechanic to each crossnumber. This started in crossnumber #13, when all the clues involved two conditions which were joined by an and, or, xor, nand, nor or xnor connective. Mechanics in later puzzles have included the clues being given in a random order without clue numbers (#14), some clues being false (#16), and each clue being satisfied by both the entry and the entry reversed (#19). I really hope that you enjoy the 'fun' mechanic I used in this issue's puzzle.

Around the same time as I started playing with additional mechanics, my taste in puzzles shifted. Older crossnumbers had been quite computational, and often needed some programming for a few of the clues, but more recently I have become a greater fan of logic puzzles and number puzzles that can be solved by hand. To reflect the change in the type of puzzle I was setting we added the phrase 'but no programming should be necessary to solve the puzzle' to the instructions, starting with crossnumber #14.

Thinking like a mega-pedant

One of the most important things to watch out from when writing and checking clues is accidental ambiguity due to writing maths in words.

For example, the clue 'A factor of 6 more than 2D' could be read in two ways: this could be asking the solver to add 6 to 2D, then find a factor of the result; or it could be asking the solver to add 1, 2, 3, or 6 (ie a factor of 6) to 2D.

As long as I spot clues like this, it can usually be fixed with some rewording. In this example, I'd rewrite the clues as either '2D plus a factor of 6.' or 'This number is a factor of the sum of 6 and 2D.'

In my time setting the crossnumber, I've got a lot better at spotting ambiguity in clues, and do this by reading through the clues and trying to be a mega-pedant and intentionally misinterpret them. It can be really helpful to get someone else to help with this check though, as remembering what you intended to mean when writing a clue can make it hard to read them critically.

Checking uniqueness

Perhaps the most difficult part of setting a crossnumber is checking that there is exactly one solution to the completed puzzle.

To help with this task, I've written a load of Python code to help me find all the solutions to the puzzle. I run this a lot while writing clues to make sure there's no area of the puzzle where I've left multiple options for a digit. I intentionally use a lot of brute force in this code so that it's really good at catching situations where there are multiple answers to a puzzle where I only found one solution by hand.

Once I've got all the clues and my code says the solution is unique, I do a full solve of the puzzle by hand. This is both to confirm that the code's conclusion was not due to a bug, and to check that the difficulty of the puzzle is reasonable.

Following this checking, and a little proofreading, the puzzle is ready for publishing. Then the fun part begins, as I get to chill with a nice cup of tea and wait for people to submit their answers.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment

2024-12-04

As usual, I spent some time this November,

designing this year's Chalkdust puzzle Christmas card

(with some help from TD).

The card contains 10 puzzles. By splitting the answers into pairs of digits, then drawing lines between the dots on the cover for each pair of digits (eg if an answer is 201304, draw a line from dot 20 to dot 13 and another line from dot 13 to dot 4), you will reveal a Christmas themed picture. Colouring any region containing an even number of unused dots green and colour any region containing an odd number of unused dots red or blue will make the picture even nicer.

If you're in the UK and want some copies of the card to send to your maths-loving friends, you can order them at mscroggs.co.uk/cards.

If you want to try the card yourself, you can download this printable A4 pdf. Alternatively, you can find the puzzles below and type the answers in the boxes. The answers will automatically be used to join the dots and the appropriate regions coloured in...

| 1. | What is the largest number you can make by using the digits 1 to 4 to make two 2-digit numbers, then mutiplying the two numbers together? | Answer |

| 2. | What is the largest number you can make by using the digits 0 to 9 to make a 2-digit number and a 8-digit number, then mutiplying the two numbers together? | Answer |

| 3. | The expansion of \((2x+3)^2\) is \(4x^2+12x+9\). The sum of the coefficients of \(4x^2+12x+9\) is 25. What is the sum of the coefficients of the expansion of \((30x+5)^2\)? | Answer |

| 4. | What is the sum of the coefficients of the expansion of \((2x+1)^{11}\)? | Answer |

| 5. | What is the geometric mean of all the factors of 41306329? | Answer |

| 6. | What is the largest number for which the geometric mean of all its factors is 92? | Answer |

| 7. | What is the sum of all the factors of \(7^4\)? | Answer |

| 8. | How many numbers between 1 and 28988500000 have an odd number of factors? | Answer |

| 9. | Eve found the total of the 365 consecutive integers starting at 500 and the total of the next 365 consecutive integers, then subtracted the smaller total from the larger total. What was her result? | Answer |

| 10. | Eve found the total of the \(n\) consecutive integers starting at a number and the total of the next \(n\) consecutive integers, then subtracted the smaller total from the larger total. Her result was 22344529. What is the largest possible value of \(n\) that she could have used? | Answer |

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

I enjoyed solving problems for this card very much! Thanks a lot! I had a great time!

Happy New Year! Greetings from Ukraine.

Happy New Year! Greetings from Ukraine.

Anna

Matt, great card this year! Problems 1 and 2 are slightly ambiguous though in that you did not specify that each digit could only be used once.

I initially thought the answers were simply 44×44 = 1936 and 99×99999999 = 9899999901, respectively ????

I initially thought the answers were simply 44×44 = 1936 and 99×99999999 = 9899999901, respectively ????

Dan Whitman

I find that I can enter seven correct answers without issue. however, an eighth answer causes the entire tree to vanish.

I'm using Firefox on Windows 11.

I'm using Firefox on Windows 11.

hakon

@HJ: I can't reproduce that error on Firefox or Chrome on Ubuntu - although I did notice I'd left some debug outputting on, which I've now removed. Perhaps that was causing the issue.

If anyone else hits this issue, please let me know.

If anyone else hits this issue, please let me know.

Matthew

On my machine (Mac, using either Firefox or Chrome, including private mode so no plugins) the puzzle disappears when I complete the answers for 1, 3 and 9. I'm presuming my answers are correct -- the pattern they create is pretty clear and looks reasonable.

HJ

Add a Comment

2023-12-08

In November, I spent some time (with help from TD) designing this year's Chalkdust puzzle Christmas card.

The card looks boring at first glance, but contains 10 puzzles. By colouring in the answers to the puzzles on the front of the card in the colours given (each answer appears four time),

you will reveal a Christmas themed picture.

If you're in the UK and want some copies of the card to send to your maths-loving friends, you can order them at mscroggs.co.uk/cards.

If you want to try the card yourself, you can download this printable A4 pdf. Alternatively, you can find the puzzles below and type the answers in the boxes. The answers will automatically be found and coloured in...

Green | ||

| 1. | What is the largest value of \(n\) such that \((n!-1)/(n-1)\) is an integer? | Answer |

| 2. | What is the largest value of \(n\) such that \((n!-44)/(n-44)\) is an integer? | Answer |

Red/blue | ||

| 3. | Holly adds up the first 7 even numbers, then adds on half of the next even number. What total does she get? | Answer |

| 4. | Holly adds up the first \(n\) even numbers, then adds on half of the next even number. Her total was 9025. What is \(n\)? | Answer |

Brown | ||

| 5. | What is the area of the quadrilateral with the largest area that will fit inside a circle with area 20π? | Answer |

| 6. | What is the area of the dodecagon with the largest area that will fit inside a circle with area 20π? | Answer |

| 7. | How many 3-digit positive integers are there whose digits are all 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 with exactly two digits that are ones? | Answer |

| 8. | Eve works out that there are 300 \(n\)-digit positive integers whose digits are all 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 with exactly \(n-1\) digits that are ones. What is \(n\)? | Answer |

| 9. | What are the last two digits of \(7^3\)? | Answer |

| 10. | What are the last two digits of \(7^{9876543210}\)? | Answer |

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Incorrect answers are treated is correct.

Looking at the JavaScript code, I found that any value that is a key in the array "regions" is treated as correct for all puzzles.

Looking at the JavaScript code, I found that any value that is a key in the array "regions" is treated as correct for all puzzles.

Lars Nordenström

My visual abilities fail me - managed to solve the puzzles but cannot see what the picture shows

Gantonian

@nochum: It can't, so the answer to that one probably isn't 88.

Matthew

how can a dodecagon with an area of 88 fit inside anything with an area of 62.83~?

nochum

Add a Comment

2023-09-02

This week, I've been at Talking Maths in Public (TMiP) in Newcastle. TMiP is a conference for anyone involved

in—or interested in getting involved in—any sort of maths outreach, enrichment, or public engagement activity. It was really good, and I highly recommend coming to TMiP 2025.

The Saturday morning at TMiP was filled with a choice of activities, including a puzzle hunt written by me: the Tyne trial.

At the start/end point of the Tyne trial, there was a locked box with a combination lock. In order to work out the combination for the lock, you needed to find some clues hidden around

Newcastle and solve a few puzzles.

Every team taking part was given a copy of these instructions.

Some people attended TMiP virtually, so I also made a version of the Tyne trial that included links to Google Street View and photos from which the necessary information could be obtained.

You can have a go at this at mscroggs.co.uk/tyne-trial/remote. For anyone who wants to try the puzzles without searching through virtual Newcastle,

the numbers that you needed to find are:

- Clue #1: \(a\) is 9.

- Clue #2: \(b\) is 5.

- Clue #3: \(c\) is 1838.

- Clue #4: \(d\) is 1931.

- Clue #5: \(e\) is 1619.

- Clue #6: \(f\) is 48.

- Clue #7: \(g\) is 1000.

The solutions to the puzzles and the final puzzle are below. If you want to try the puzzles for yourself, do that now before reading on.

Puzzle for clue #2: Palindromes

We are going to start with a number then repeat the following process: if the number you have is a palindrome, stop;

otherwise add the number to itself backwards.

For example, if we start with 219, then we do: $$219\xrightarrow{+912}1131\xrightarrow{+1311}2442.$$

If you start with the number \(10b+9\) (ie 59), what palindrome do you get?

(If you start with 196, it is unknown whether you will ever get a palindrome.)

Puzzle for clue #3: Mostly ones

There are 12 three-digit numbers whose digits are 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 with exactly two digits that are ones.

How many \(c\)-digit (ie 1838-digit) numbers are there whose digits are 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 with exactly \(c-1\) digits (ie 1837) that are ones?

Puzzle for clue #4: is it an integer?

The largest value of \(n\) such that \((n!-2)/(n-2)\) is an integer is 4. What is the largest value of \(n\) such that

\((n!-d)/(n-d)\) (ie \((n!-1931)/(n-1931)\)) is an integer?

Puzzle for clue #5: How many steps?

We are going to start with a number then repeat the following process:

if we've reached 0, stop; otherwise subtract the smallest prime factor of the current number.

For example, if we start with 9, then we do: $$9\xrightarrow{-3}6\xrightarrow{-2}4\xrightarrow{-2}2\xrightarrow{-2}0.$$ It took 4 steps to get to 0.

What is the smallest starting number such that this process will take \(e\) (ie 1619) steps?

Puzzle for clue #6: Four-digit number

I thought of a four digit number. I removed a

digit to make a three digit number, then added my two numbers together.

The result is \(200f+127\) (ie 9727). What was my original number?

Puzzle for clue #7: Dice

If you roll two six-sided fair dice, the most likely total is 7. What is the most likely total if you rolled \(1470+g\) (ie 2470) dice?

The final puzzle

The final puzzle involves using the answers to the five puzzles to find the four digit code that

opens the box (and the physical locked box that was in the library on

Saturday. To give hints to this code, each clue was given a "score".

The score of a number is the number of values of \(i\) such that the \(i\)th digit

of the code is a factor of the \(i\)th digit of the number.

For example, if the code was 1234, then the score of the number 3654 would be 3 (because

1 is a factor of 3; 2 is a factor of 6; and 4 is a factor of 4).

The seven clues to the final code are:

- Clue #1: 6561 scores 2 points.

- Clue #2: 1111 scores 0 points.

- Clue #3: 7352 scores 1 points.

- Clue #4: 3562 scores 1 points.

- Clue #5: 3238 scores 1 points.

- Clue #6: 8843 scores 1 points.

- Clue #7: 8645 scores 3 points.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment

Image: Chalkdust Magazine

Chalkdust issue 17

2023-05-22

For the past couple of months, I've once again been spending an awful lot of my spare time working

on Chalkdust. Today you can see the result of all this hard work: Chalkdust issue 17.

I recommend checking out the entire magazine: you can read it online

or order a physical copy.

My most popular contribution to the magazine is probably the crossnumber.

I enjoyed writing this one; hope you enjoy solving it.

I also spent some time making this for the back page of the magazine. It's probably the most

fun I've had making something stupid for Chalkdust for ages.

Chalkdust Magazine

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment