Blog

2022-02-26

Surprisingly often, people ask me how they can build their own copy of MENACE. If you've been thinking that you'd love your own matchbox-powered machine learning computer but haven't got round to asking me about it yet, then this blog post is just what you're looking for.

Matchboxes

Before building MENACE, you'll need to get hold of 304 matchboxes (plus a few spares in case one gets lost or falls apart). I used these craft matchboxes: they don't have the best build quality, but they're good enough.

304 positions

The positions you need to glue onto the front of the matchboxes can be downloaded from this GitHub repository (first move boxes, third move boxes, fifth move boxes, seventh move boxes). These are sized to fit on matchboxes that have 15mm by 35mm fronts.

I printed each pdf on differently coloured paper to make it easier to sort the matchboxes after getting them out of their box.

If you get differently sized matchboxes, the code used the generate the PDFs is in the same GitHub repository (you'll need to modify these lines). Alternatively, feel free to drop me an email and I will happily adjust the sizes for you and send you the updated PDFs.

Glue

I used PVA glue to stick the positions onto the matchboxes. The printable PDFs have extra tabs of paper above and below the postions that can be glued in to the bottom and inside of the matchbox tray to hold it more securely.

Gluing the positions onto the matchboxes was the most time consuming part of building my copy of MENACE, largely due to having to wait for the glue to dry on a set of matchboxes before I had space for the next batch of them to dry.

Beads

Once you've glued pictures of noughts and crosses positions to 304 matchboxes, you'll need to put coloured beads into each matchbox. For this, I used a large tub of Hama beads (that tub contained orders of magnitude more beads than I needed).

A nice side effect of using Hama beads is that they're designed to be ironed together so making a key to show which colour corresponds to each position is very easy.

I typically start the boxes off with 8 beads of each colour in the first move box, 4 of each colour in the third move boxes, 2 of each in the fifth move boxes, and one of each in the seventh move boxes.

Once you've filled all your matchboxes with the correct number of beads, you're ready to play yout first game against MENACE. I'd love to hear how you get on.

And once you're bored of playing noughts and crosses against your matchboxes, why not build a machine that learns to play Hexapawn, Connect 4, Chess or Go? Or one that plays Nim?

Edit: Added link to the printable pdfs of the positions needed for Hexapawn, made by Dan Whitman.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

I also read the Martin Gardner article way back when and had two matchbox machines (actually with envelopes instead of matchboxes) play Nim against each other. I don't remember all the details now, except that it got to the point where one would make the first move and the other would immediately resign.

Tim Lewis

I made a matchbox machine that learns to play 3x3 Nim almost 50 years ago. I still have it. (Based on Martin Gardner's article)

Tony

Add a Comment

2019-12-27

In tonight's Royal Institution Christmas lecture,

Hannah Fry and Matt Parker demonstrated how machine learning works using MENACE.

The copy of MENACE that appeared in the lecture was build and trained by me. During the training, I logged all the moved made by MENACE and the humans playing against them, and using this data I have

created some visualisations of the machine's learning.

First up, here's a visualisation of the likelihood of MENACE choosing different moves as they play games. The thickness of each arrow represented the number of beads in the box corresponding to that move,

so thicker arrows represent more likely moves.

The likelihood that MENACE will play each move.

There's an awful lot of arrows in this diagram, so it's clearer if we just visualise a few boxes. This animation shows how the number of beads in the first box changes over time.

You can see that MENACE learnt that they should always play in the centre first, an ends up with a large number of green beads and almost none of the other colours. The following

animations show the number of beads changing in some other boxes.

MENACE learns that the top left is a good move.

MENACE learns that the middle right is a good move.

MENACE is very likely to draw from this position so learns that almost all the possible moves are good moves.

The numbers in these change less often, as they are not used in every game: they are only used when the game reached the positions shown on the boxes.

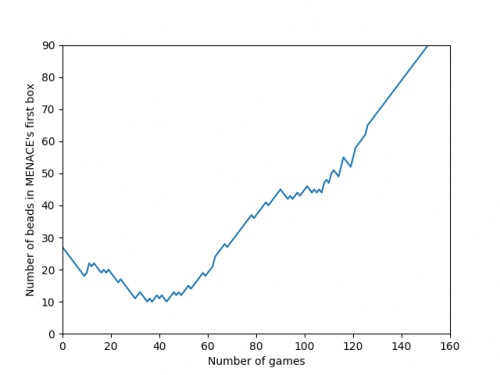

We can visualise MENACE's learning progress by plotting how the number of beads in the first box changes over time.

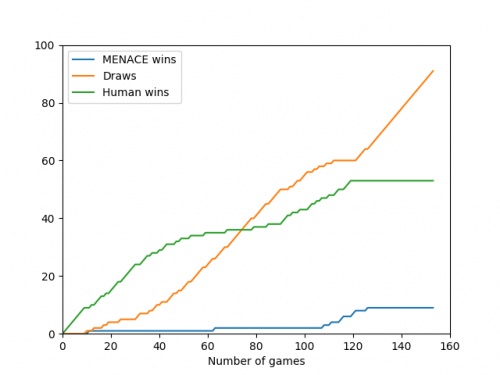

Alternatively, we could plot how the number of wins, loses and draws changes over time or view this as an animated bar chart.

The number of games MENACE wins, loses and draws.

The number of games MENACE has won, lost and drawn.

If you have any ideas for other interesting ways to present this data, let me know in the comments below.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

@(anonymous): Have you been refreshing the page? Every time you refresh it resets MENACE to before it has learnt anything.

It takes around 80 games for MENACE to learn against the perfect AI. So it could be you've not left it playing for long enough? (Try turning the speed up to watch MENACE get better.)

It takes around 80 games for MENACE to learn against the perfect AI. So it could be you've not left it playing for long enough? (Try turning the speed up to watch MENACE get better.)

Matthew

I have played around menace a bit and frankly it doesnt seem to be learning i occasionally play with it and it draws but againt the perfect ai you dont see as many draws, the perfect ai wins alot more

(anonymous)

@Colin: You can set MENACE playing against MENACE2 (MENACE that plays second) on the interactive MENACE. MENACE2's starting numbers of beads and incentives may need some tweaking to give it a chance though; I've been meaning to look into this in more detail at some point...

Matthew

Idle pondering (and something you may have covered elsewhere): what's the evolution as MENACE plays against itself? (Assuming MENACE can play both sides.)

Colin

Add a Comment

2018-12-16

By now, you've probably noticed that I like teaching matchboxes to play noughts and crosses.

Thanks to comments on Hacker News, I discovered that I'm not the only one:

MENACE has appeared in, or inspired, a few works of fiction.

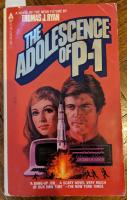

The Adolescence of P-1

The Adolescence of P-1 by Thomas J Ryan [1] is the story of Gregory Burgess, a computer programmer who writes a computer program that becomes sentient.

P-1, the program in question, then gets a bit murdery as it tries to prevent humans from deactivating it.

The first hint of MENACE in this book comes early on, in chapter 2, when Gregory's friend Mike says to him:

"Because I'm a veritable fount of information. From me you could learn such wonders as the gestation period of an elephant or how to teach a matchbox to win at tic-tac-toe."Taken from The Adolescence of P-1 by Thomas J Ryan [1], page 27

A few years later, in chapter 4, Gregory is talking to Mike again. Gregory asks:

"... How do you teach a matchbox to play tic-tac toe?""What?""You heard me. I remember you once said you could teach a matchbox. How?""Jesus Christ! Let me think . . . Yeah . . . I remember now. That was an article in Scientific American quite a few years ago. It was a couple of years old when I mentioned it to you, I think.""How does it work?""Pretty good. Same principal of reward and punishment you use to teach a dog tricks, as I remember. Actually, you get several matchboxes. One for each possible move you might make in a game of tic-tac-toe. You label them appropriately, then you put an equal number of two different coloured beads in each box. The beads correspond to each yes/no decision you can make in a game. When a situation is reached, you grab the box for the move, shake it up, and grab a bead out of it. The bead indicates the move. You make a record of that box and color, and then make the opposing move yourself. You move against the boxes. If the boxes lose the game, you subtract a bead of the color you used from each of the boxes you used. If they win, you add a bead of the appropriate color to the boxes you used. The boxes lose quite a few games, theoretically, and after the bad moves start getting eliminated or statistically reduced to inoperative levels, they start to win. Then they never lose. Something like that. Check Scientific American about four years ago. How is this going to help you?"Taken from The Adolescence of P-1 by Thomas J Ryan [1], pages 41-42

The article in Scientific American that they're talking about is obviously A matchbox game learning-machine by Martin Gardner [2].

Mike, unfortunately, hasn't quite remembered perfectly how MENACE works: rather than having two colours in each box for yes and no, each box actually has a different colour for each possible move that could be made next.

But to be fair to Mike, he read the article around two years before this conversation so this error is forgivable.

In any case, this error didn't hold Gregory back, as he quickly proceeded to write a program, called P-1 inspired by MENACE.

P-1 was first intended to learn to connect to other computers through their phone connections and take control of their supervisor, but then

Gregory failed to close the code and it spent a few years learning everything it could before contacting Gregory, who was obviously a little

surprised to hear from it.

P-1 has also learnt to fear, and is scared of being deactiviated. With Gregory's help, P-1 moves much of itself to a more secure location.

Without telling Gregory, P-1 also attempts to get control of America's nuclear weapons to obtain its own nuclear deterrent, and starts

using its control over computer systems across America to kill anyone that threatens it.

Apart from a few Literary Review Bad Sex in Fiction Award worthy segments,

The Adolescence of P-1 is an enjoyable read.

Hide and Seek (1984)

In 1984, The Adolescence of P-1 was made into a Canadian TV film called Hide and Seek [3].

It doesn't seem to have made it to DVD, but luckily the whole film is on

YouTube.

About 24 minutes into the film, Gregory explains to Jessica how he made P-1:

Gregory: First you end up with random patterns like this. Now there are certain rules: if a cell has one or two neighbours, it reproduces into the next generation. If it has no neighbours, it dies of loneliness. More than two it dies of overcrowding. Press the return key.Jessica: Okay. [pause] And this is how you created P-1?Gregory: Well, basically. I started to change the rules and then I noticed that the patterns looked like computer instructions. So I entered them as a program and it worked.Hide and Seek [3] (1984)

This is a description of a cellular automaton similar to Game of Life, and not a great way to make a machine that learns.

I guess the film's writers have worse memories than Gregory's friend Mike.

In fact, apart from the character names and the murderous machine, the plots of The Adolescence of P-1 and Hide and Seek don't have much in common.

Hide and Seek does, however, have a lot of plot elements in common with WarGames [4].

WarGames (1983)

In 1983, the film WarGames was released. It is the story of David, a hacker that tries to hack into a video game company's computer, but accidentally

hacks into the US governments computer and starts a game of Global thermonuclear war. At least David thinks it's a game, but actually

the computer has other ideas, and does everything in its power to actually start a nuclear war.

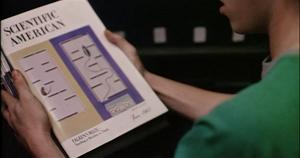

During David's quests to find out more about the computer and prevent nuclear war, he learns about its creator, Stephen Falken.

He describes him to his girlfriend, Jennifer:

David: He was into games as well as computers. He designed them so that they could play checkers or poker. Chess.Jennifer: What's so great about that? Everybody's doing that now.David: Oh, no, no. What he did was great! He designed his computer so it could learn from its own mistakes. So they'd be better they next time they played. The system actually learned how to learn. It could teach itself.WarGames [4] (1983)

Although David doesn't explain how the computer learns, he at least states that it does learn, which is more than Gregory managed in Hide and Seek.

David's research into Stephen Falken included finding an article called Falken's maze: Teaching a machine to learn in

June 1963's issue of Scientific American. This article and Stephen Falken are fictional, but perhaps its appearance in Scientific American

is a subtle nod to Martin Gardner and A matchbox game learning-machine.

WarGames was a successful film: it was generally liked by viewers and nominated for three Academy Awards. It seems likely that the creators of

Hide and Seek were really trying to make their own version of WarGames, rather than an accurate apatation of The Adolescence of P-1. This perhaps explains the similarities

between the plots of the two films.

Without a Thought

Without a Thought by Fred Saberhagen [5] is a short story published in 1963. It appears in a collection of related short stories by Fred Saberhagen called Bezerker.

In the story, Del and his aiyan (a pet a bit like a more intelligent dog; imagine a cross between R2-D2 and Timber) called Newton are in a spaceship fighting against a bezerker. The bezerker has

a mind weapon that pauses all intelligent thought, both human and machine. The weapon has no effect

on Newton as Newton's thought is non-intelligent.

The bezerker challenges Del to a simplified checker game, and says that if Del can play the game while the mind weapon is active, then he

will stop fighting.

After winning the battle, Del explains to his commander how he did it:

But the Commander was watching Del: "You got Newt to play by the following diagrams, I see that. But how could he learn the game?"Del grinned. "He couldn't, but his toys could. Now wait before you slug me" He called the aiyan to him and took a small box from the animal's hand. The box rattled faintly as he held it up. On the cover was pasted a diagram of on possible position in the simplified checker game, with a different-coloured arrow indicating each possible move of Del's pieces.It took a couple of hundred of these boxes," said Del. "This one was in the group that Newt examined for the fourth move. When he found a box with a diagram matching the position on the board, he picked the box up, pulled out one of these beads from inside, without looking – that was the hardest part to teach him in a hurry, by the way," said Del, demonstrating. "Ah, this one's blue. That means, make the move indicated on the cover by the blue arrow. Now the orange arrow leads to a poor position, see?" Del shook all the beads out of the box into his hand. "No orange beads left; there were six of each colour when we started. But every time Newton drew a bead, he had orders to leave it out of the box until the game was over. Then, if the scoreboard indicated a loss for our side, he went back and threw away all the beads he had used. All the bad moves were gradually eliminated. In a few hours, Newt and his boxes learned to play the game perfectly."Taken from Without a Thought by Fred Saberhagen [5]

It's a good thing the checkers game was simplified, as otherwise the number of boxes needed to play would be

way too big.

Overall, Without a Thought is a good short story containing an actually correctly explained machine learning algorithm. Good job Fred Saberhagen!

References

[1] The Adolescence of P-1 by Thomas J Ryan. 1977.

[4] WarGames. 1993.

[5] Without a Thought by Fred Saberhagen. 1963.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment

2018-04-29

Two years ago, I built a copy of MENACE (Machine Educable Noughts And Crosses Engine). Since then, it's been to many Royal Institution masterclasses, visted Manchester and met David Attenborough. When I'm not showing them off, the 304 matchboxes that make up my copy of MENACE live in this box:

This box isn't very big, which might lead you to wonder how big MENACE-style machines would be for other games.

Hexapawn (HER)

In A matchbox game learning-machine by Martin Gardner [1], the game of Hexapawn was introduced. Hexapawn is played on a 3×3 grid, and starts with three pawns facing three pawns.

The pieces move like pawns: they may be either moved one square forwards into an empty square, or take another pawn diagonally (the pawns are not allowed to move forwards two spaces on their first move, as they can in chess).

You win if one of your pawns reaches the other end of the board. You lose if none of your pieces can move.

The game was invented by Martin Gardner as a good game for his readers to build a MENACE-like machine to play against, as there are only 19 positions that can face player two, so only 19 matchboxes are needed to make HER (Hexapawn Educable Robot). (HER plays as player two, as if player two plays well they can always win.)

Nine Men's Morris (MEME)

In Nine Men's Morris, two players first take turns to place pieces on the board, before taking turns to move pieces to adjacent spaces. If three pieces are placed in a row, a player may remove one of the opponent's pieces. It's a bit like Noughts and Crosses, but with a bit more chance of it not ending in a draw.

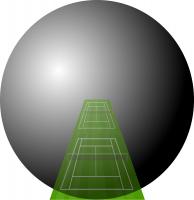

In Solving Nine Men's Morris by Ralph Gasser [2], the number of possible game states in Nine Men's Morris is given as approximately \(10^{10}\). To build MEME (Machine Educable Morris Engine), you would need this many matchboxes. These boxes would form a sphere with radius 41m: that's approximately the length of two tennis courts.

As a nice bonus, if you build MEME, you'll also smash the world record for the largest matchbox collection.

Connect 4 (COFFIN)

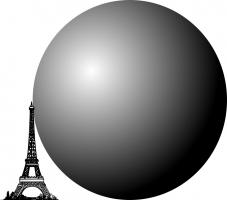

In Symbolic classification of general two-player games by Stefan Edelkamp and Peter Kissmann [3], the number of possible game states in Connect 4 is given as 4,531,985,219,092. The boxes used to make COFFIN (COnnect Four Fighting INstrument) would make a sphere with radius 302m: approximately the height of the Eiffel Tower.

In Solving the game of Checkers by Jonathan Schaeffer and Robert Lake [4], the number of possible game states in Draughts is given as approximately \(5\times10^{20}\). The boxes needed to build DOCILE (Draughts Or Checkers Intelligent Learning Engine) would make a sphere with radius 151km.

DOCILE: Draughts Or Checkers Intelligent Learning Engine

If the centre of DOCILE was in London, some of the boxes would be in Sheffield.

Chess (CLAWS)

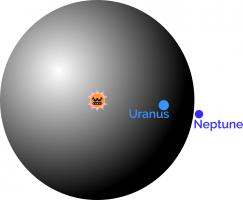

The number of possible board positions in chess is estimated to be around \(10^{43}\). The matchboxes needed to make up CLAWS (Chess Learning And Winning System) would fill a sphere with radius \(4\times10^{12}\)m.

If the Sun was at the centre of CLAWS, you might have to travel past Uranus on your search for the right box.

Go (MEGA)

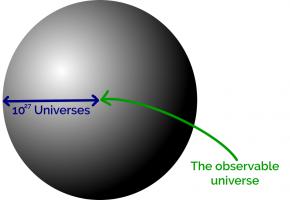

The number of possible positions in Go is estimated to be somewhere near \(10^{170}\). To build MEGA (Machine Educable Go Appliance), you're going to need enough matchboxes to make a sphere with radius \(8\times10^{54}\)m.

The observable universe takes up a tiny space at the centre of this sphere. In fact you could fit around \(10^{27}\) copies of the universe side by side along the radius of this sphere.

It's going to take you a long time to look through all those matchboxes to find the right one...

References

[3] Symbolic classification of general two-player games by Stefan Edelkamp and Peter Kissmann. in Advances in Artificial Intelligence (edited by A.R. Dengel, K. Berns, T.M. Breuel, F. Bomarius, T.R. Roth-Berghofer), 2008. [link]

[4] Solving the game of Checkers by Jonathan Schaeffer and Robert Lake. Games of No Chance 29, 1996. [link]

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Kind of like the "Blue Brain Project". They got a worm and fruitfly brain on the computer, I wanted to download the fruitfly brain for 2GB USB stick but it was over 12 TB. They uploaded half a mouse brain on their project so far.

Willem

Would Love to play with Coffin/Coffin2. Do you have the code on git or a JS/web version?... been kind of thinking of coding a version that only makes the match boxes as it needs them (to save on memory) but I heard you already have a version with optimizations (and my coding skill is rough at best)

John

Are you aware of any actual implementations of anything in matchboxes, games or otherwise?

Jam

Of course, to make CLAWS, you will have to leave a large gap in the centre of the matchbox sphere, to avoid the very real danger of fire. Furthermore, some redundancy is needed, to replace the boxes which will be damaged by the myriad hard objects which are whizzing around the solar system. For this latter reason alone, I propose that the machine would be impractical to make! ;-D

g0mrb

Add a Comment

2018-01-05

In 1969, Sid Sackson published his magnum opus:

A Gamut of Games,

a collection of 38 games that can all be played with pen and paper or a pack of cards.

One of the best games I've tried so far from the book is James Dunnigan's Origins of World War I.

The original version from the book gets you to start by drawing a large table to play on, and during play requires a fair bit of flicking

backwards and forwards to check the rules. To make playing easier, I made

this handy pdf that contains all the information you need to play the game.

The rules

Starting

Origins of World War I is a game for five players (although it can be played with 3 or 4 people; details at the end).

To play you will need a printed copy of the pdf, a pen or pencil, and a 6-sided dice.

Each player picks one of the five nations along the top of the board: Britain, France, Germany, Russia, or Austria–Hungary.

Once you've picked your countries, you are ready to begin.

Taking a turn

The countries take turns in the order Britain, France, Germany, Russia, or Austria–Hungary: the same order the countries are written

across the top and down the side of the board. A player's turn involves two things: (1) adding "political factors";

(2) carrying out a "diplomatic attack".

First the player adds political factors (PFs). On their turn, Britain adds 14 PFs, France adds 12 PFs, Germany adds 16 PFs, Russia adds 10 PFs,

and Austria–Hungary adds 10 PFs. These numbers are shown under the names of the countries on the left hand side of the board. A player

can add at most 5 PFs to each country per turn, although they may add as many PFs as they like to their own country. The number of PFs

a player adds to each country should be written in the boxes in the players column.

For example, Britain may choose to add 5 PFs in Italy, 2 in the Far East and 12 in Britain. This would be added to the board by writing

the relevant numbers in the Italy, Far East and Britain rows of the Britain column.

After adding PFs, a player may choose to carry out a diplomatic attack. If so the player chooses one of the other four players to attack,

and a country in which this attack takes place. Both players must have some PFs in the country where the attack takes place. The dice is rolled.

The outcome of the attack depends on how much the attacker outnumbers the defender and the value rolled: these are shown to the right of the board.

The three possible outcomes are: Attacker Eliminated (AE), which causes the attacker's PFs in this country to be reduced to 0;

Exchange (EX), which causes both players' PFs in this country to be reduced by the same amount so that one player is left with 0;

and Defender Eliminated (DE), wich causes the defender's PFs in this country to be reduced to 0.

For example, Britain may choose to attack Germany in Africa. If Britain and Germany have 10 and 4 PFs in Africa (respectively), then Britain

outnumbers Germany 2 to 1. The dice is rolled.

If a 1 is rolled, the attacker (Britain) is eliminated, leaving Britain on 0 and Germany on 4.

If one of 2-5 is rolled, the players exchange, leaving Britain on 6 and Germany on 0.

If a 6 is rolled, the defender (Germany) is eliminated, leaving Britain on 10 and Germany on 0.

The game ends after each play has played 10 turns. The number of turns may be kept track of by crossing out a number in the Turn Counter

to the right of the board after each round of 5 turns.

Scoring

If a player has 10 or more PFs in a country, then they have Treaty Rights (TR) with that country. Each player scores point by achieving TR

with other countries. TR are not symmetric: if Russia has TR with Germany, then this does not mean that Germany automatically has TR with Russia.

The number of points scored by a player for obtaining TR with other countries are printed in the boxes on the board. The numbers in brackets

are only scored if the TR are exclusive: ie if no other country also has TR with that country. Additionally, points are awarded to Britain, France and Germany

if the objectives in the boxes at the foot of their columns are satisfied.

For example, Britain scores 3 points if they have TR with Italy, 1 point if they have TR with Greece, 2 points if they have TR with Turkey.

and 4 points if they have exclusive TR with the Far East. Britain also scores 10 points if no other nation has more than 12 points.

Alliances

During the game, players are encouraged to make deals with other players: for example, Britain may agree to not add PFs in Serbia if

Russia agrees to carry diplomatic attacks against Germany in Bulgaria. Deals can of course be broken by either player later in the game.

Two players may also enter into a more formal alliance, leading to their two nations working together for the rest of the game. These

alliances may not be broken. If two players are allied, then at the end of the game, their scores are added: if this total is higher than the

scores of the other three players combined, then the allies win; if not, then the highest score among the other three wins.

During a game, it is possible for two different alliances to form (these must be between two different pairs of nations: a country cannot form

two alliances, and three countries cannot form a three-way alliance). In this case, a pair of allies wins if their combined score is larger

than the combined score of the other three players. If neither pair of allies scores this high, the unallied player wins.

Playing with 3 or 4 players

Alliances can be used to play Origins of World War I with fewer than 5 players. To play with four players, an alliance can be

formed at the start of the game, with one player playing both nations in the alliance. To play with three players, the game can be started with

two alliances already in place.

If you've ready this far, then you're now fully prepared to play Origins of World War I, so print the pdf,

invite 4 friends over, and have a game...

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment

Could try a same kind of thing using playing card deck(s)? A(=1)-2-3 4-5-6 7-8-9 maybe 3 decks with different colours on their backs.