Blog

2021-05-22

In this post I'd like to talk about the catchily named Stirling numbers of the second kind, which I first encountered in this Maths Stack Exchange post. I'll start with some motivation for Stirling numbers of the second kind, show how they can be recursively calculated, and then show some interesting features of these numbers.

Suppose a fair die has \(f\) distinct faces, and suppose you roll it \(n\) times. What's the probability that you roll exactly \(k\) distinct faces? Since the die is fair, each sequence of rolls is equally likely, so the probability is given by

$$

\frac{\text{number of ways to roll the die \(n\) times and observe \(k\) distinct faces}}{\text{number of sequences of \(n\) rolls}}.

$$

The number of possible sequences of \(n\) rolls is just \(f^{n}\). And since, if we see exactly \(k\) distinct faces, the \(k\) distinct faces are equally likely to be any of the subsets of size \(k\) out of \(f\). So we have:

$$

\begin{array}{lr}

\text{ways to observe \(k\) distinct faces in \(n\) rolls}\hspace{-7cm}&\\[-7mm]&= (\text{ways to observe \(\{1, 2, \dots, k\}\) in \(n\) rolls}) \times \displaystyle\binom{f}{k}.

\end{array}

$$

Let's think about breaking down the \(n\) rolls into \(k\) subsets based on which rolls matched each face. For example, if \(k = 3\) and the sequence of rolls was \(\{1, 2, 1, 2, 3, 1\}\), then the three subsets would be \(\{1, 3, 6\}, \{2, 4\}\), and \(\{5\}\), where the first subset is \(\{1, 3, 6\}\) because rolls 1, 3, and 6 were face 1. Since each of the \(k\) faces was observed, each subset must be non-empty. Any permutation of these subsets still creates a valid sequence of observations, eg if we swapped the first two subsets then the subsets would correspond to the sequence of rolls \(\{2, 1, 2, 1, 3, 2\}\). And since there are \(k!\) to permute the subsets, we have that the probability is

$$

(\text{ways to partition \(n\) items into \(k\) non-empty subsets}) \times \binom{f}{k} \times k! \times f^{-n}.

$$

The number of ways to partition \(n\) items into \(k\) non-empty subsets is a Stirling number of the second kind, denoted \(\left\{n\atop k\right\}\).

In the same way that the factorial function is technically defined recursively,

$$

x! =

\begin{cases}

1 & \text{if } x = 0,\\

(x - 1)! \thinspace x & \text{if } x > 0,

\end{cases}

$$

we can define the Stirling number of the second kind recursively. If \(n = 0\) and \(k = 0\), then the probability of seeing \(k\) distinct numbers in \(n\) rolls is 1, so we set \(\left\{0\atop 0\right\} = 1\). If \(n \geq 1\) then we are guaranteed to see at least \(1\) distinct face, so \(\left\{n\atop 0\right\} = 0\). If \(n = 0\) and \(k\geq1\), then seeing \(k\) faces is impossible, so \(\left\{0\atop k\right\} = 0\). And if \(k > n\) then seeing \(k\) distinct faces in \(n\) rolls is impossible, so \(\left\{n\atop k\right\} = 0\). These give us the base cases for a recursion. The recursive formula for \(n, k \geq 1\) is given by

$$

\left\{n\atop k\right\} = \left\{n - 1\atop k-1\right\} + k \left\{n - 1\atop k\right\}.

$$

To see why, consider splitting \(n\) items into \(k\) non-empty subsets, and suppose that \(n - 1\) of the items have already been added to subsets. We will consider two cases. In one case, the \(n - 1\) items have only been assigned to \(k - 1\) subsets (making each of these \(k-1\) subsets non-empty) and we are forced to use the \(n\)th item to make the \(k\)th subset non-empty. There are \(\left\{n-1\atop k-1\right\}\) ways that \(n-1\) items can be assigned to make \(k-1\) non-empty subsets, hence the first term in the sum. In the second case, the \(n-1\) items have already been assigned to all \(k\) subsets (making each of the \(k\) subsets non-empty), and we are free to choose which of the \(k\) subsets to put the \(n\)th item in. There are \(\left\{n-1\atop k\right\}\) ways that \(n-1\) items can be assigned to make \(k\) non-empty subsets, and \(k\) choices for the \(n\)th item, hence the second term in the sum.

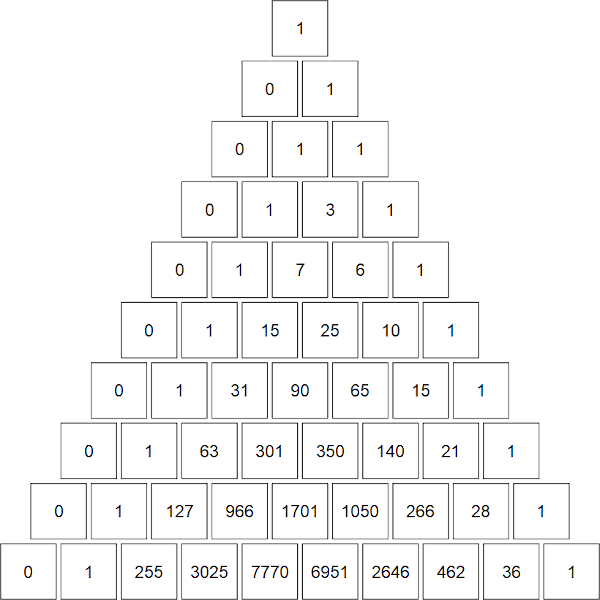

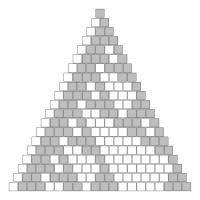

The plot shows a "Pascal's triangle" for the Stirling numbers of the second kind, which I call "Stirling's second triangle". The top square is \(\left\{0\atop 0\right\}\), the next row contains \(\left\{1\atop 0\right\}, \left\{1\atop 1\right\}\), and so on.

The top ten rows of "Stirling's second triangle"

You can see how the generating rule differs from the one for \(\binom nk\). Instead of

$$

\binom{n}{k} = \binom{n - 1}{k - 1} + \binom{n - 1}{k}

$$

we have our recursive formula. Let's do the 5th row (corresponding to \(n = 4\)) as an example. We know from the base cases that \(\left\{4\atop 0\right\} = 0\). Then \(\left\{4\atop 1\right\} = 0 + 1 \times 1 = 1\), \(\left\{4\atop 2\right\} = 1 + 2 \times 3 = 7\), \(\left\{4\atop 3\right\} = 3 + 3 \times 1 = 6\), and \(\left\{4\atop 4\right\} = 1 + 4 \times 0 = 1\).

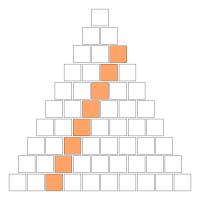

The diagonal \(\left\{2\atop 2\right\}\), \(\left\{3\atop 2\right\}\), \(\left\{4\atop 2\right\}\), \(\left\{5\atop 2\right\}\), \(\left\{6\atop 2\right\}\), ...

The diagonals in this triangle have some interesting features. Consider the diagonal \(\left\{2\atop 2\right\}\), \(\left\{3\atop 2\right\}\), \(\left\{4\atop 2\right\}\), \(\left\{5\atop 2\right\}\), \(\left\{6\atop 2\right\}\), ... = 1, 3, 7, 15, 31, ... = \(2^1 - 1\), \(2^2 - 1\), \(2^3 - 1\), \(2^4 - 1\), \(2^5 - 1\), ... The triangular numbers 0, 1, 3, 6, 10, 15, ... also make an appearance. I will leave it as an exercise for the reader to show that

$$

\left\{n\atop 2\right\} = 2^{n-1} - 1,$$$$\text{ and } \left\{n\atop n-1\right\} = \binom{n}{2}.

$$

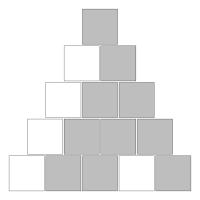

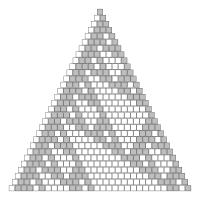

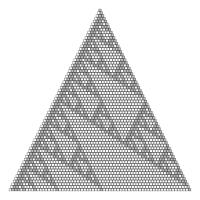

Finally, an interesting feature occurs if you shade in the "Stirling's second triangle" according to the parity of the entry. Let the odd numbers be shaded grey and the white numbers be shaded white. At first it is difficult to discern a pattern, but it a fractal pattern related to the Sierpiński triangle emerges.

The top five rows of "Stirling's second triangle" coloured by parity.

The top twenty rows of "Stirling's second triangle" coloured by parity.

The top thirty rows of "Stirling's second triangle" coloured by parity.

The top sixty-six rows of "Stirling's second triangle" coloured by parity.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment