Blog

2018-12-16

By now, you've probably noticed that I like teaching matchboxes to play noughts and crosses.

Thanks to comments on Hacker News, I discovered that I'm not the only one:

MENACE has appeared in, or inspired, a few works of fiction.

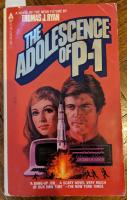

The Adolescence of P-1

The Adolescence of P-1 by Thomas J Ryan [1] is the story of Gregory Burgess, a computer programmer who writes a computer program that becomes sentient.

P-1, the program in question, then gets a bit murdery as it tries to prevent humans from deactivating it.

The first hint of MENACE in this book comes early on, in chapter 2, when Gregory's friend Mike says to him:

"Because I'm a veritable fount of information. From me you could learn such wonders as the gestation period of an elephant or how to teach a matchbox to win at tic-tac-toe."Taken from The Adolescence of P-1 by Thomas J Ryan [1], page 27

A few years later, in chapter 4, Gregory is talking to Mike again. Gregory asks:

"... How do you teach a matchbox to play tic-tac toe?""What?""You heard me. I remember you once said you could teach a matchbox. How?""Jesus Christ! Let me think . . . Yeah . . . I remember now. That was an article in Scientific American quite a few years ago. It was a couple of years old when I mentioned it to you, I think.""How does it work?""Pretty good. Same principal of reward and punishment you use to teach a dog tricks, as I remember. Actually, you get several matchboxes. One for each possible move you might make in a game of tic-tac-toe. You label them appropriately, then you put an equal number of two different coloured beads in each box. The beads correspond to each yes/no decision you can make in a game. When a situation is reached, you grab the box for the move, shake it up, and grab a bead out of it. The bead indicates the move. You make a record of that box and color, and then make the opposing move yourself. You move against the boxes. If the boxes lose the game, you subtract a bead of the color you used from each of the boxes you used. If they win, you add a bead of the appropriate color to the boxes you used. The boxes lose quite a few games, theoretically, and after the bad moves start getting eliminated or statistically reduced to inoperative levels, they start to win. Then they never lose. Something like that. Check Scientific American about four years ago. How is this going to help you?"Taken from The Adolescence of P-1 by Thomas J Ryan [1], pages 41-42

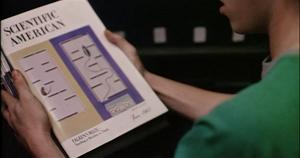

The article in Scientific American that they're talking about is obviously A matchbox game learning-machine by Martin Gardner [2].

Mike, unfortunately, hasn't quite remembered perfectly how MENACE works: rather than having two colours in each box for yes and no, each box actually has a different colour for each possible move that could be made next.

But to be fair to Mike, he read the article around two years before this conversation so this error is forgivable.

In any case, this error didn't hold Gregory back, as he quickly proceeded to write a program, called P-1 inspired by MENACE.

P-1 was first intended to learn to connect to other computers through their phone connections and take control of their supervisor, but then

Gregory failed to close the code and it spent a few years learning everything it could before contacting Gregory, who was obviously a little

surprised to hear from it.

P-1 has also learnt to fear, and is scared of being deactiviated. With Gregory's help, P-1 moves much of itself to a more secure location.

Without telling Gregory, P-1 also attempts to get control of America's nuclear weapons to obtain its own nuclear deterrent, and starts

using its control over computer systems across America to kill anyone that threatens it.

Apart from a few Literary Review Bad Sex in Fiction Award worthy segments,

The Adolescence of P-1 is an enjoyable read.

Hide and Seek (1984)

In 1984, The Adolescence of P-1 was made into a Canadian TV film called Hide and Seek [3].

It doesn't seem to have made it to DVD, but luckily the whole film is on

YouTube.

About 24 minutes into the film, Gregory explains to Jessica how he made P-1:

Gregory: First you end up with random patterns like this. Now there are certain rules: if a cell has one or two neighbours, it reproduces into the next generation. If it has no neighbours, it dies of loneliness. More than two it dies of overcrowding. Press the return key.Jessica: Okay. [pause] And this is how you created P-1?Gregory: Well, basically. I started to change the rules and then I noticed that the patterns looked like computer instructions. So I entered them as a program and it worked.Hide and Seek [3] (1984)

This is a description of a cellular automaton similar to Game of Life, and not a great way to make a machine that learns.

I guess the film's writers have worse memories than Gregory's friend Mike.

In fact, apart from the character names and the murderous machine, the plots of The Adolescence of P-1 and Hide and Seek don't have much in common.

Hide and Seek does, however, have a lot of plot elements in common with WarGames [4].

WarGames (1983)

In 1983, the film WarGames was released. It is the story of David, a hacker that tries to hack into a video game company's computer, but accidentally

hacks into the US governments computer and starts a game of Global thermonuclear war. At least David thinks it's a game, but actually

the computer has other ideas, and does everything in its power to actually start a nuclear war.

During David's quests to find out more about the computer and prevent nuclear war, he learns about its creator, Stephen Falken.

He describes him to his girlfriend, Jennifer:

David: He was into games as well as computers. He designed them so that they could play checkers or poker. Chess.Jennifer: What's so great about that? Everybody's doing that now.David: Oh, no, no. What he did was great! He designed his computer so it could learn from its own mistakes. So they'd be better they next time they played. The system actually learned how to learn. It could teach itself.WarGames [4] (1983)

Although David doesn't explain how the computer learns, he at least states that it does learn, which is more than Gregory managed in Hide and Seek.

David's research into Stephen Falken included finding an article called Falken's maze: Teaching a machine to learn in

June 1963's issue of Scientific American. This article and Stephen Falken are fictional, but perhaps its appearance in Scientific American

is a subtle nod to Martin Gardner and A matchbox game learning-machine.

WarGames was a successful film: it was generally liked by viewers and nominated for three Academy Awards. It seems likely that the creators of

Hide and Seek were really trying to make their own version of WarGames, rather than an accurate apatation of The Adolescence of P-1. This perhaps explains the similarities

between the plots of the two films.

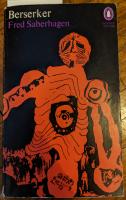

Without a Thought

Without a Thought by Fred Saberhagen [5] is a short story published in 1963. It appears in a collection of related short stories by Fred Saberhagen called Bezerker.

In the story, Del and his aiyan (a pet a bit like a more intelligent dog; imagine a cross between R2-D2 and Timber) called Newton are in a spaceship fighting against a bezerker. The bezerker has

a mind weapon that pauses all intelligent thought, both human and machine. The weapon has no effect

on Newton as Newton's thought is non-intelligent.

The bezerker challenges Del to a simplified checker game, and says that if Del can play the game while the mind weapon is active, then he

will stop fighting.

After winning the battle, Del explains to his commander how he did it:

But the Commander was watching Del: "You got Newt to play by the following diagrams, I see that. But how could he learn the game?"Del grinned. "He couldn't, but his toys could. Now wait before you slug me" He called the aiyan to him and took a small box from the animal's hand. The box rattled faintly as he held it up. On the cover was pasted a diagram of on possible position in the simplified checker game, with a different-coloured arrow indicating each possible move of Del's pieces.It took a couple of hundred of these boxes," said Del. "This one was in the group that Newt examined for the fourth move. When he found a box with a diagram matching the position on the board, he picked the box up, pulled out one of these beads from inside, without looking – that was the hardest part to teach him in a hurry, by the way," said Del, demonstrating. "Ah, this one's blue. That means, make the move indicated on the cover by the blue arrow. Now the orange arrow leads to a poor position, see?" Del shook all the beads out of the box into his hand. "No orange beads left; there were six of each colour when we started. But every time Newton drew a bead, he had orders to leave it out of the box until the game was over. Then, if the scoreboard indicated a loss for our side, he went back and threw away all the beads he had used. All the bad moves were gradually eliminated. In a few hours, Newt and his boxes learned to play the game perfectly."Taken from Without a Thought by Fred Saberhagen [5]

It's a good thing the checkers game was simplified, as otherwise the number of boxes needed to play would be

way too big.

Overall, Without a Thought is a good short story containing an actually correctly explained machine learning algorithm. Good job Fred Saberhagen!

References

[1] The Adolescence of P-1 by Thomas J Ryan. 1977.

[4] WarGames. 1993.

[5] Without a Thought by Fred Saberhagen. 1963.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment