Blog

2016-03-15

This article first appeared in

issue 03 of

Chalkdust. I highly recommend reading the rest of the magazine (and trying

to solve the crossnumber I wrote for the issue).

It all began in December 1956, when an article about hexaflexagons was published in Scientific American. A hexaflexagon is a

hexagonal paper toy which can be folded and then opened out to reveal hidden faces. If you have never made a hexaflexagon, then you should stop

reading and make one right now. Once you've done so, you will understand why the article led to a craze in New York;

you will probably even create your own mini-craze because you will just need to show it to everyone you know.

The author of the article was, of course, Martin Gardner.

Martin Gardner was born in 1914 and grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He earned a bachelor's degree in philosophy from the University of Chicago and

after four years serving in the US Navy during the Second World War, he returned to Chicago and began writing. After a few years working on

children's magazines and the occasional article for adults, Gardner was introduced to John Tukey, one of the students who had been involved in

the creation of hexaflexagons.

Soon after the impact of the hexaflexagons article became clear, Gardner was asked if he had enough material to maintain a monthly column.

This column, Mathematical Games, was written by Gardner every month from January 1956 for 26 years until December 1981. Throughout its run,

the column introduced the world to a great number of mathematical ideas, including Penrose tiling, the Game of Life, public key encryption,

the art of MC Escher, polyominoes and a matchbox machine learning robot called MENACE.

Life

Gardner regularly received topics for the column directly from their inventors. His collaborators included Roger Penrose, Raymond Smullyan,

Douglas Hofstadter, John Conway and many, many others. His closeness to researchers allowed him to write about ideas that

the general public were previously unaware of and share newly researched ideas with the world.

In 1970, for example, John Conway invented the Game of Life, often simply referred to as Life. A few weeks later, Conway showed the game to Gardner, allowing

him to write the first ever article about the now-popular game.

In Life, cells on a square lattice are either alive (black) or dead (white). The status of the cells in the next generation of the game is given by the following

three rules:

- Any live cell with one or no live neighbours dies of loneliness;

- Any live cell with four or more live neighbours dies of overcrowding;

- Any dead cell with exactly three live neighbours becomes alive.

For example, here is a starting configuration and its next two generations:

The collection of blocks on the right of this game is called a glider, as it will glide to the right and upwards as the generations advance.

If we start Life with a single glider, then the glider will glide across the board forever, always covering five squares: this starting position

will not lead to the sad ending where everything is dead. It is not obvious, however, whether there is a starting

configuration that will lead the number of occupied squares to increase without bound.

Originally, Conway and Gardner thought that this was impossible, but after the article was published, a reader and mathematician called Bill Gosper

discovered the glider gun: a starting arrangement in Life that fires a glider every 30 generations. As each of these gliders will go on to live

forever, this starting configuration results in the number of live cells

perpetually increasing!

This discovery allowed Conway to prove that any Turing machine can be built within Life: starting

arrangements exist that can calculate the digits of pi, solve equations, or do any other calculation a computer is capable of (although very slowly)!

Encrypting with RSA

To encode the message \(809\), we will use the public key:

$$s=19\quad\text{and}\quad r=1769$$

The encoded message is the remainder when the message to the power of \(s\) is divided by \(r$:

$$809^{19}\equiv\mathbf{388}\mod1769$$

Decrypting with RSA

To decode the message, we need the two prime factors of \(r\) (\(29\) and \(61\)).

We multiply one less than each of these together:

\begin{align*}

a&=(29-1)\times(61-1)\\[-2pt]

&=1680.

\end{align*}

We now need to find a number \(t\) such that \(st\equiv1\mod a\). Or in other words:

$$19t\equiv1\mod 1680$$

One solution of this equation is \(t=619\) (calculated via the extended Euclidean algorithm).

Then we calculate the remainder when the encoded message to the power of \(t\) is divided by \(r\):

$$388^{619}\equiv\mathbf{809}\mod1769$$

RSA

Another concept that made it into Mathematical Games shortly after its discovery was public key cryptography. In mid-1977, mathematicians Ron

Rivest, Adi Shamir and Leonard Adleman invented the method of encryption now known as RSA (the initials of their surnames). Here,

messages are encoded using two publicly shared numbers, or keys. These numbers and the method used to encrypt messages can be publicly shared as

knowing this information does not reveal how to decrypt the message. Rather, decryption of the message requires knowing the prime factors of one of the keys. If this key is the product of two very large

prime numbers, then this is a very difficult task.

Something to think about

Gardner had no education in maths beyond high school, and at times had difficulty understanding the material he was writing about. He believed, however, that this was a strength and not a weakness: his struggle to understand led him to write in a way that other non-mathematicians could follow. This goes a long way to explaining the popularity of his column.

After Gardner finished working on the column, it was continued by Douglas Hofstadter and then AK Dewney before being passed down to Ian Stewart.

Gardner died in May 2010, leaving behind hundreds of books and articles. There could be no better way to end than with something for you to go

away and think about. These of course all come from Martin Gardner's Mathematical Games:

- Find a number base other than 10 in which 121 is a perfect square.

- Why do mirrors reverse left and right, but not up and down?

- Every square of a 5-by-5 chessboard is occupied by a knight.

- Is it possible for all 25 knights to move simultaneously in such a way that at the finish all cells are still occupied as before?

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment

2016-01-01

The deadline for entering the 2015 Advent calendar competition has now passed. You can see all the puzzles and their answers here.

Thank-you to everyone who took part in the competition! In total, 23 people submitted answers to the puzzles. Every one of these had correct answers to at least 18 of the puzzles. The winners are as follows:

| # | Name | Details |

| 1 | Scott | All correct at 5:00:18 GMT on Christmas Day |

| 2 | Louis de Mendonca | All correct at 5:00:32 GMT on Christmas Day |

| 3 | Alex Bolton | All correct at 5:00:34 GMT on Christmas Day |

| 4 | Martin Harris | All correct at 6:15 GMT on Christmas Day |

| 5 | Linus Hamilton | All correct at 14:12 GMT on Christmas Day |

| 6 | Zephi | All correct at 20:40 GMT on Christmas Day |

| 7 | Daniel Chiverton | All but one (5 December) correct at 5:00:24 GMT on Christmas Day |

| 8 | Jon Palin | All but one (12 December) correct at 5:00:34 GMT on Christmas Day |

| 9 | Kathryn Coffin | All but one (5 December) correct at 6:28 GMT on Christmas Day |

| 10 | Félix Breton | All but one (15 December) correct at 9:05 GMT on Christmas Day |

I will be in touch will all the entrants in the next few days and I will post pictures of prizes here once they are on their way!

I have already started working on puzzles for next year's (in fact this year's) calendar, so make sure you're back here in December...

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

@stephan: It looks like the code I wrote to check the solutions were unique contained errors. This might explain why first question was very difficult to solve with logic alone.

Matthew

Are you sure http://www.mscroggs.co.uk/puzzles/126 have unique solutions. See e.g. http://cryptarithms.awardspace.us/solv... which gives lots of solutions

stephan

Add a Comment

2015-11-24

This year, the front page of mscroggs.co.uk will feature an advent calendar. Behind each door, there will be a puzzle with a three digit solution.

As you solve the puzzles, your answers will be stored in a cookie. Behind the door on Christmas Day, there will be a form allowing you to submit your answers. The first person to submit the correct answers will win this array of prizes:

The prizes include an mscroggs.co.uk t-shirt, a DVD of Full Frontal Nerdity and a beautiful mscroggs.co.uk 2015 winner's medal:

I will be adding to the pile of prizes throughout December.

The next nine people to submit the correct answers will win a winner's medal plus a smaller goody bag of prizes. If less than ten correct entries are submitted, prizes will be given to those with one incorrect answer, then those with two incorrect answers and so on.

Each day's puzzle (and the entry form on Christmas Day) will be available from 5:00am GMT.

To win a prize, you must submit your entry before the start of 2016. Only one entry will be accepted per person. Once ten correct entries have been submitted, I will add a note here and below the calendar. If you have any questions, ask them in the comments below or on Twitter.

So once December is here, get solving! Good luck and have a very merry Christmas!

Edit: The winners and answers can now be found here.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

@Anonymous2: Other winners and answers will be available from 1st January

Matthew

How many wrong answers do I have ? And when will you publish the solutions ?

Anonymous2

@Anonymous1: You are (now) correct and on the leaderboard. Well done!

Matthew

I've submitted my answer! On Christmas too! It's just that I sorta crammed all of the answers today :/

Are you allowed to tell me if I am correct?

Are you allowed to tell me if I am correct?

Anonymous1

Add a Comment

2015-10-21

This post also appeared on the Chalkdust Magazine blog.

If you're like me, then you will be disappointed that all of the home nations have been knocked out of the Rugby World Cup. If you're really like me, doing some maths related to rugby will cheer you up...

The scoring system in rugby awards points in packets of 3, 5 and 7. This leads a number of interesting questions that you can find in my guest puzzle on Alex Bellos's Guardian blog. In this blog post, we will focus on another area of rugby: conversion kicking.

Conversion kicks

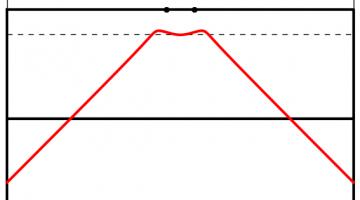

When a try is scored by putting the ball down behind the line, the scoring team gets to take a conversion kick. This kick must be taken in line with where the try was scored but it is up to the kicker how far away the kick should be taken. But how far back should the ball be taken to make the kick easiest?

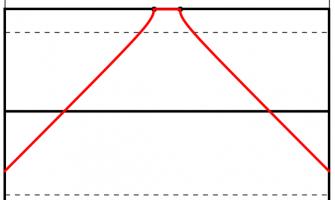

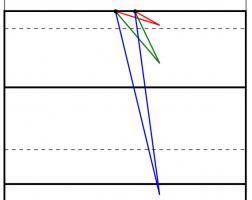

Too close (red) and too far away (blue) will give small angles to aim at. Somewhere in the middle is needed (green).

One way to answer this question is to look to maximise the angle between the posts which the kicker will have to aim at: if the kick is taken too close to or too far from the goal line there will be a very thin angle to aim at. Somewhere between these extremes there will be a maximum angle to aim at.

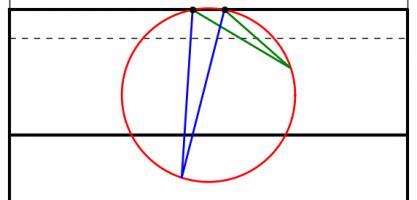

When looking to maximise this angle, we can use one of the 'circle theorems' which have tormented many generations of GCSE maths students: 'angles subtended by the same arc at the circumference are equal'. This means that if a circle is drawn going through both posts, then the angle made at any point on this circle will be the same.

The angles made by the red and blue lines are equal because 'angles subtended by the same arc at the circumference are equal'.

A larger circle drawn through the posts will give a smaller angle. If a vertical line is drawn which just touches the right of the circle, then the point at which it touches the circle will be the best place on this line to take a kick. This is because any other point on the line will be on a larger circle and so make a smaller angle.

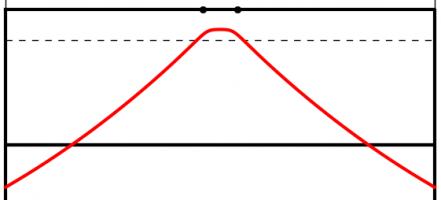

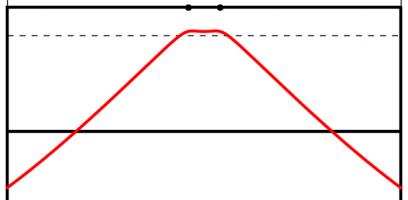

Using this method for circles of different sizes leads to the following diagram, which shows where the kick should be taken for every position a try could be scored:

This, however, is not the best place to take the kick.

Taking account of height

When a try is scored near the posts, the above method recommends a position from where the ball must be kicked at an impossibly steep angle to go over. To deal with this problem, we are going to have to look at the situation from the side.

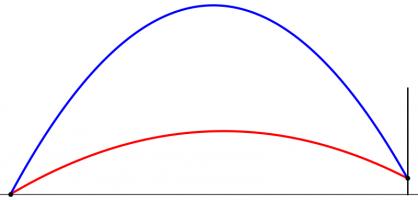

When kicked, the ball will travel along a parabola (ignoring air resistance and wind as their effects will be small[citation needed]). Given a distance from the posts, there will be two angles which the ball can be kicked at and just make it over the bar. Kicking at any angle between these two will lead to a successful conversion. Again, we have an angle which we would like to maximise.

However, the position where this angle is maximised is very unlikely to also maximise the angle we looked at earlier. To find the best place to kick from, we need to find a compromise point where both angles are quite big.

To do this, imagine that the kicker is standing inside a large sphere. For each point on the sphere, kicking the ball at the point will either lead to it going over or missing. We can draw a shape on the sphere so that aiming inside the shape will lead to scoring. Our sensible kicker will aim at the centre of this shape.

But our kicker will not be able to aim perfectly: there will be some random variation. We can predict that this variation will follow a Kent distribution, which is like a normal distribution but on the surface of a sphere. We can use this distribution to calculate the probability that our kicker will score. We would like to maximise this probability.

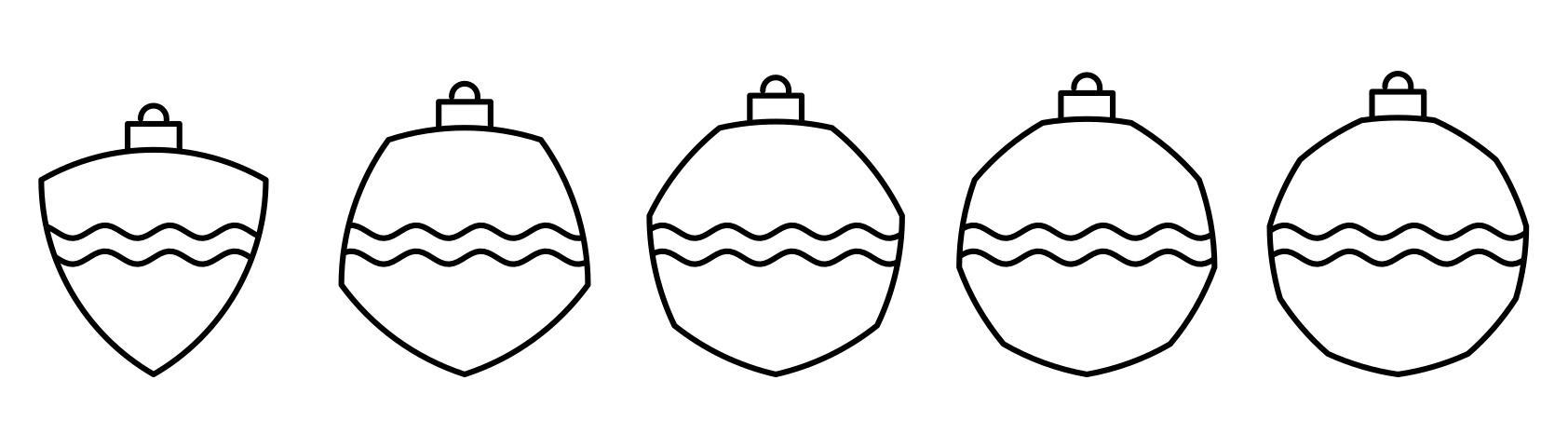

The Kent distribution can be adjusted to reflect the accuracy of the kicker. Below are the optimal kicking positions for an inaccurate, an average and a very accurate kicker.

The best place to take a kick for a bad kicker (top), an average kicker (middle) and a good kicker (bottom). All the kickers kick the ball at 30m/s.

As you might expect, the less accurate kicker should stand slightly further forwards to make it easier to aim. Perhaps surprisingly, the good kicker should stand further back when between the posts than when in line with the posts.

The model used to create these results could be further refined. Random variation in the speed of the kick could be introduced. Or the kick could be made to have more variation horizontally than vertically: there are parameters in the Kent distribution which allow this to be easily adjusted. In fact, data from players could be used to determine the best position for each player to kick from.

In addition to analysing conversions, this method could be used to determine the probability of scoring 3 points from any point on the pitch. This could be used in conjunction with the probability of scoring a try from a line-out to decide whether kicking a penalty for the posts or into touch is likely to lead to the most points.

Although estimating the probability of scoring from a line-out is a difficult task. Perhaps this will give you something to think about during the remaining matches of the tournament.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment

2015-10-08

This post also appeared on the Chalkdust Magazine blog. You can read the excellent second issue of Chalkdust here, including the £100 prize crossnumber which I set.

From today, the National Lottery's Lotto draw has 59 balls instead of 49. You may be thinking that this means there is now much less chance of winning. You would be right, except the prizes are also changing.

Camelot, who run the lottery, are saying that you are now "more likely to win a prize" and "more likely to become a millionaire". But what do these changes actually mean?

The changes

Until yesterday, Lotto had 49 balls. From today, there are 59 balls. Each ticket still has six numbers on it and six numbers, plus a bonus ball, are still chosen by the lottery machine. The old prizes were as follows:

| Requirement | Estimated Prize |

| Match all 6 normal balls | £2,000,000 |

| Match 5 normal balls and the bonus ball | £50,000 |

| Match 5 normal balls | £1,000 |

| Match 4 normal balls | £100 |

| Match 3 normal balls | £25 |

| 50 randomly picked tickets | £20,000 |

The prizes have changed to:

| Requirement | Estimated Prize |

| Match all 6 normal balls | £2,000,000 |

| Match 5 normal balls and the bonus ball | £50,000 |

| Match 5 normal balls | £1,000 |

| Match 4 normal balls | £100 |

| Match 3 normal balls | £25 |

| Match 2 normal balls | Free lucky dip entry in next Lotto draw |

| One randomly picked ticket | £1,000,000 |

| 20 other randomly picked tickets | £20,000 |

Probability of Winning a Prize

The probability of winning each of these prizes can be calculated. For example, the probability of matching all 6 balls in the new lotto is $$\mathbb{P}(\mathrm{matching\ ball\ 1})\times \mathbb{P}(\mathrm{matching\ ball\ 2})\times...\times\mathbb{P}(\mathrm{matching\ ball\ 6})$$ $$=\frac{6}{59}\times\frac{5}{58}\times\frac{4}{57}\times\frac{3}{56}\times\frac{2}{55}\times\frac{1}{54}$$ $$=\frac{1}{45057474},$$ and the probability of matching 4 balls in the new lotto is $$(\mathrm{number\ of\ different\ ways\ of\ picking\ four\ balls\ out\ of\ six})\times\mathbb{P}(\mathrm{matching\ ball\ 1})\times\\...\times\mathbb{P}(\mathrm{matching\ ball\ 4})\times\mathbb{P}(\mathrm{not\ matching\ ball\ 5})\times\mathbb{P}(\mathrm{not\ matching\ ball\ 6})$$ $$=15\times\frac{6}{59}\times\frac{5}{58}\times\frac{4}{57}\times\frac{3}{56}\times\frac{53}{55}\times\frac{52}{54}$$ $$=\frac{3445}{7509579}.$$ In the second calculation, it is important to include the probabilities of not matching the other balls to prevent double counting the cases when more than 4 balls are matched.

Calculating a probability for every prize and then adding them up gives the probability of winning a prize. In the old draw, the probability of winning a prize was \(0.0186\). In the new draw, it is \(0.1083\). So Camelot are correct in claiming that you are now more likely to win a prize.

But not all prizes are equal: these probabilities do not take into account the values of the prizes. To analyse the actual winnings, we're going to have to look at the expected amount of money you will win. But first, let's look at Camelot's other claim: that under the new rules you are more likely to become a millionaire.

Probability of winning £1,000,000

In the old draw, the only way to win a million pounds was to match all six balls. The probability of this happening was \(0.00000007151\) or \(7.151\times 10^{-8}\).

In the new lottery, a million pounds can be won either by matching all six balls or by winning the millionaire raffle. This will lead to different probabilities of winning on Wednesdays and Saturdays due to different numbers of people buying tickets. Based on expected sales of 16.5 million tickets on Saturdays and 8.5 million tickets on Wednesdays, the chances of becoming a millionaire on a Wednesday or Saturday are \(0.0000001398\) (\(1.398\times 10^{-7}\)) and \(0.00000008280\) (\(8.280\times 10^{-8}\)) respectively.

These are both higher than the probability of winning a million in the old draw, so again Camelot are correct: you are now more likely to become a millionaire...

But the new chances of becoming a millionaire are actually even higher. The probabilities given above are the chances of winning a million in a given draw. But if two balls are matched, you win a lucky dip: you could win a million in the next draw without buying another ticket. We should include this in the probability calculated above, as you are still becoming a millionaire due to the original ticket you bought.

In order to count this, let \(A_W\) and \(A_S\) be the probabilities of winning a million in a given draw (as given above) on a Wednesday or a Saturday, let \(B_W\) and \(B_S\) be the probabilities of winning a million in this draw or due to future lucky dip tickets on a Wednesday or a Saturday (the values we want to find) and let \(p\) be the probability of matching two balls. We can write $$B_W=A_W+pB_S$$ and $$B_S=A_S+pB_W$$ since the probability of winning a million is the probability of winning in this draw (\(A\)) plus the probability of winning a lucky dip ticket and winning in the next draw (\(pB\)). Substituting and rearranging, we get $$B_W=\frac{A_W+pA_S}{1-p^2}$$ and $$B_W=\frac{A_S+pA_W}{1-p^2}.$$

Using this (and the values of \(A_S\) and \(A_W\) calculated earlier) gives us probabilities of \(0.0000001493\) (\(1.493\times 10^{-7}\)) and \(0.00000009736\) (\(9.736\times 10^{-8}\)) of becoming a millionaire on a Wednesday and a Saturday respectively. These are both significantly higher than the probability of becoming a millionaire in the old draw (\(7.151\times 10^{-8}\)).

Camelot's two claims—that you are more likely to win a prize and you are more likely to become a millionaire—are both correct. It sounds like the new lottery is a great deal, but so far we have not taken into account the size of the prizes you will win and have only shown that a very rare event will become slightly less rare. Probably the best way to measure how good a lottery is is by working out the amount of money you should expect to win, so let's now look at that.

Expected prize money

To find the expected prize money, we must multiply the value of each prize by the probability of winning that prize and then add them up, or, in other words,

$$\sum_\mathrm{prizes}\mathrm{value\ of\ prize}\times\mathbb{P}(\mathrm{winning\ prize}).$$

Once this has been calculated, the chance of winning due to a free lucky dip entry must be taken into account as above.

In the old draw, after buying a ticket for £2, you could expect to win 78p or 83p on a Wednesday or Saturday respectively. In the new draw, the expected winnings have changed to 58p and 50p (Wednesday and Saturday respectively). Expressed in this way, it can be seen that although the headline changes look good, the overall value for money of the lottery has significantly decreased.

Looking on the bright side, this does mean that the lottery will make even more money that it can put towards charitable causes: the lottery remains an excellent way to donate your money to worthy charities!

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment