Blog

2016-03-15

This article first appeared in

issue 03 of

Chalkdust. I highly recommend reading the rest of the magazine (and trying

to solve the crossnumber I wrote for the issue).

It all began in December 1956, when an article about hexaflexagons was published in Scientific American. A hexaflexagon is a

hexagonal paper toy which can be folded and then opened out to reveal hidden faces. If you have never made a hexaflexagon, then you should stop

reading and make one right now. Once you've done so, you will understand why the article led to a craze in New York;

you will probably even create your own mini-craze because you will just need to show it to everyone you know.

The author of the article was, of course, Martin Gardner.

Martin Gardner was born in 1914 and grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He earned a bachelor's degree in philosophy from the University of Chicago and

after four years serving in the US Navy during the Second World War, he returned to Chicago and began writing. After a few years working on

children's magazines and the occasional article for adults, Gardner was introduced to John Tukey, one of the students who had been involved in

the creation of hexaflexagons.

Soon after the impact of the hexaflexagons article became clear, Gardner was asked if he had enough material to maintain a monthly column.

This column, Mathematical Games, was written by Gardner every month from January 1956 for 26 years until December 1981. Throughout its run,

the column introduced the world to a great number of mathematical ideas, including Penrose tiling, the Game of Life, public key encryption,

the art of MC Escher, polyominoes and a matchbox machine learning robot called MENACE.

Life

Gardner regularly received topics for the column directly from their inventors. His collaborators included Roger Penrose, Raymond Smullyan,

Douglas Hofstadter, John Conway and many, many others. His closeness to researchers allowed him to write about ideas that

the general public were previously unaware of and share newly researched ideas with the world.

In 1970, for example, John Conway invented the Game of Life, often simply referred to as Life. A few weeks later, Conway showed the game to Gardner, allowing

him to write the first ever article about the now-popular game.

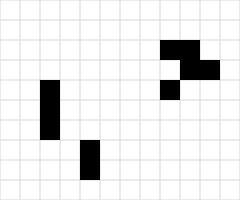

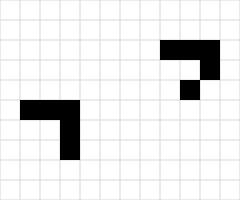

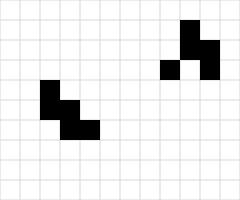

In Life, cells on a square lattice are either alive (black) or dead (white). The status of the cells in the next generation of the game is given by the following

three rules:

- Any live cell with one or no live neighbours dies of loneliness;

- Any live cell with four or more live neighbours dies of overcrowding;

- Any dead cell with exactly three live neighbours becomes alive.

For example, here is a starting configuration and its next two generations:

The collection of blocks on the right of this game is called a glider, as it will glide to the right and upwards as the generations advance.

If we start Life with a single glider, then the glider will glide across the board forever, always covering five squares: this starting position

will not lead to the sad ending where everything is dead. It is not obvious, however, whether there is a starting

configuration that will lead the number of occupied squares to increase without bound.

Originally, Conway and Gardner thought that this was impossible, but after the article was published, a reader and mathematician called Bill Gosper

discovered the glider gun: a starting arrangement in Life that fires a glider every 30 generations. As each of these gliders will go on to live

forever, this starting configuration results in the number of live cells

perpetually increasing!

This discovery allowed Conway to prove that any Turing machine can be built within Life: starting

arrangements exist that can calculate the digits of pi, solve equations, or do any other calculation a computer is capable of (although very slowly)!

Encrypting with RSA

To encode the message \(809\), we will use the public key:

$$s=19\quad\text{and}\quad r=1769$$

The encoded message is the remainder when the message to the power of \(s\) is divided by \(r$:

$$809^{19}\equiv\mathbf{388}\mod1769$$

Decrypting with RSA

To decode the message, we need the two prime factors of \(r\) (\(29\) and \(61\)).

We multiply one less than each of these together:

\begin{align*}

a&=(29-1)\times(61-1)\\[-2pt]

&=1680.

\end{align*}

We now need to find a number \(t\) such that \(st\equiv1\mod a\). Or in other words:

$$19t\equiv1\mod 1680$$

One solution of this equation is \(t=619\) (calculated via the extended Euclidean algorithm).

Then we calculate the remainder when the encoded message to the power of \(t\) is divided by \(r\):

$$388^{619}\equiv\mathbf{809}\mod1769$$

RSA

Another concept that made it into Mathematical Games shortly after its discovery was public key cryptography. In mid-1977, mathematicians Ron

Rivest, Adi Shamir and Leonard Adleman invented the method of encryption now known as RSA (the initials of their surnames). Here,

messages are encoded using two publicly shared numbers, or keys. These numbers and the method used to encrypt messages can be publicly shared as

knowing this information does not reveal how to decrypt the message. Rather, decryption of the message requires knowing the prime factors of one of the keys. If this key is the product of two very large

prime numbers, then this is a very difficult task.

Something to think about

Gardner had no education in maths beyond high school, and at times had difficulty understanding the material he was writing about. He believed, however, that this was a strength and not a weakness: his struggle to understand led him to write in a way that other non-mathematicians could follow. This goes a long way to explaining the popularity of his column.

After Gardner finished working on the column, it was continued by Douglas Hofstadter and then AK Dewney before being passed down to Ian Stewart.

Gardner died in May 2010, leaving behind hundreds of books and articles. There could be no better way to end than with something for you to go

away and think about. These of course all come from Martin Gardner's Mathematical Games:

- Find a number base other than 10 in which 121 is a perfect square.

- Why do mirrors reverse left and right, but not up and down?

- Every square of a 5-by-5 chessboard is occupied by a knight.

- Is it possible for all 25 knights to move simultaneously in such a way that at the finish all cells are still occupied as before?

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment

2015-08-27

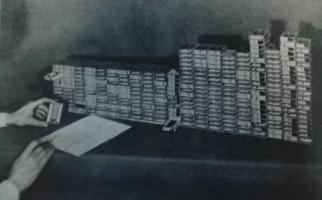

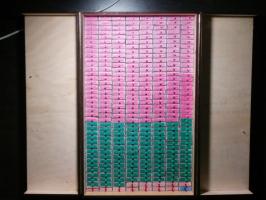

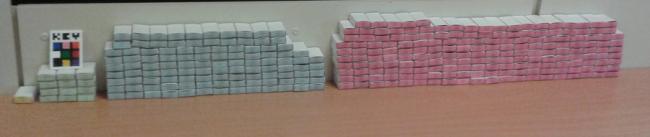

In 1961, Donald Michie built MENACE (Machine Educable Noughts And Crosses Engine), a machine capable of learning to be a better player of Noughts and Crosses (or Tic-Tac-Toe if you're American). As computers were less widely available at the time, MENACE was built from from 304 matchboxes.

Taken from Trial and error by Donald Michie [2]

The original MENACE.

To save you from the long task of building a copy of MENACE, I have written a JavaScript version of MENACE, which you can play against here.

How to play against MENACE

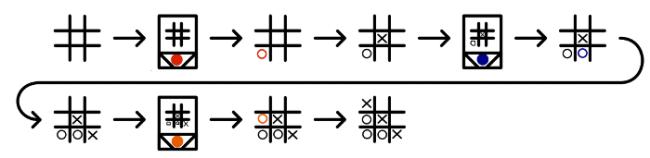

To reduce the number of matchboxes required to build it, MENACE always plays first. Each possible game position which MENACE could face is drawn on a matchbox. A range of coloured beads are placed in each box. Each colour corresponds to a possible move which MENACE could make from that position.

To make a move using MENACE, the box with the current board position must be found. The operator then shakes the box and opens it. MENACE plays in the position corresponding to the colour of the bead at the front of the box.

For example, in this game, the first matchbox is opened to reveal a red bead at its front. This means that MENACE (O) plays in the corner. The human player (X) then plays in the centre. To make its next move, MENACE's operator finds the matchbox with the current position on, then opens it. This time it gives a blue bead which means MENACE plays in the bottom middle.

The human player then plays bottom right. Again MENACE's operator finds the box for the current position, it gives an orange bead and MENACE plays in the left middle. Finally the human player wins by playing top right.

MENACE has been beaten, but all is not lost. MENACE can now learn from its mistakes to stop the happening again.

How MENACE learns

MENACE lost the game above, so the beads that were chosen are removed from the boxes. This means that MENACE will be less likely to pick the same colours again and has learned. If MENACE had won, three beads of the chosen colour would have been added to each box, encouraging MENACE to do the same again. If a game is a draw, one bead is added to each box.

Initially, MENACE begins with four beads of each colour in the first move box, three in the third move boxes, two in the fifth move boxes and one in the final move boxes. Removing one bead from each box on losing means that later moves are more heavily discouraged. This helps MENACE learn more quickly, as the later moves are more likely to have led to the loss.

After a few games have been played, it is possible that some boxes may end up empty. If one of these boxes is to be used, then MENACE resigns. When playing against skilled players, it is possible that the first move box runs out of beads. In this case, MENACE should be reset with more beads in the earlier boxes to give it more time to learn before it starts resigning.

How MENACE performs

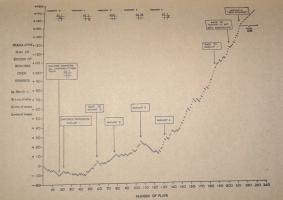

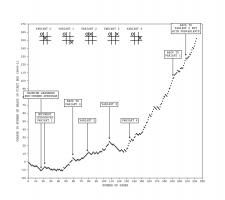

In Donald Michie's original tournament against MENACE, which lasted 220 games and 16 hours, MENACE drew consistently after 20 games.

Taken from Trial and error by Donald Michie [2]

Graph showing MENACE's performance in the original tournament. Edit: Added the redrawn graph on the left.

After a while, Michie tried playing some more unusual games. For a while he was able to defeat MENACE, but MENACE quickly learnt to stop losing. You can read more about the original MENACE in A matchbox game learning-machine by Martin Gardner [1] and Trial and error by Donald Michie [2].

You may like to experiment with different tactics against MENACE yourself.

Play against MENACE

I have written a JavaScript implemenation of MENACE for you to play against. The source code for this implementation is available on GitHub.

When playing this version of MENACE, the contents of the matchboxes are shown on the right hand side of the page. The numbers shown on the boxes show how many beads corresponding to that move remain in the box. The red numbers show which beads have been picked in the current game.

The initial numbers of beads in the boxes and the incentives can be adjusted by clicking Adjust MENACE's settings above the matchboxes. My version of MENACE starts with more beads in each box than the original MENACE to prevent the early boxes from running out of beads, causing MENACE to resign.

Additionally, next to the board, you can set MENACE to play against random, or a player 2 version of MENACE.

Edit: After hearing me do a lightning talk about MENACE at CCC, Oliver Child built a copy of MENACE. Here are some pictures he sent me:

Edit: Oliver has written about MENACE and the version he built in issue 03 of Chalkdust Magazine.

Edit: Inspired by Oliver, I have built my own MENACE. I took it to the MathsJam Conference 2016. It looks like this:

References

[2] Trial and error by Donald Michie. Penguin Science Survey, 1961.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

This is very neat. I wonder how long it would take to use that many matches to get all those match boxes.

Duke Nukem

"When playing against skilled players, it is possible that the first move box runs out of beads. In this case, MENACE should be reset with more beads in the earlier boxes to give it more time to learn before it starts resigning."

If someone were doing this, you could do this automatically to avoid the perception or temptation of the operator to help it along. Instead of "oh, it's dead, let's repopulate the boxes", you could just make it part of the inter-game cleanup, like a garbage collection routine. After all the bead deleting/adding whatever, but before the next game starts, look at all the boxes, make sure that each box contains at least one of each color. Now this weakens the learning algorithm moderately, but it guarantees that it will never get stuck.

If someone were doing this, you could do this automatically to avoid the perception or temptation of the operator to help it along. Instead of "oh, it's dead, let's repopulate the boxes", you could just make it part of the inter-game cleanup, like a garbage collection routine. After all the bead deleting/adding whatever, but before the next game starts, look at all the boxes, make sure that each box contains at least one of each color. Now this weakens the learning algorithm moderately, but it guarantees that it will never get stuck.

(anonymous)

@(anonymous): Yes, those boxes are for O being MENACE and MENACE playing first

Matthew

@Matthew: Thank you for such a quick response. Just to let you know that that link did not work after .../tree/master/output, but I managed to search around for the right files :). In these files MENACE plays the Nought right? and the user plays the Cross?

(anonymous)

@Finlay: You can find them at https://github.com/mscroggs/MENACE-pdf.... The files boxes0.pdf to boxes3.pdf are the boxes for a MENACE that plays first.

Matthew

Add a Comment

2015-03-25

This is an article which I wrote for the

first issue of

Chalkdust. I highly recommend reading the rest of the magazine (and trying

to solve the crossnumber I wrote for the issue).

In the classic arcade game Pac-Man, the player moves the title character through a maze. The aim of

the game is to eat all of the pac-dots that are spread throughout the maze while avoiding the ghosts

that prowl it.

While playing Pac-Man recently, my concentration drifted from the pac-dots and I began to think

about the best route I could take to complete the level.

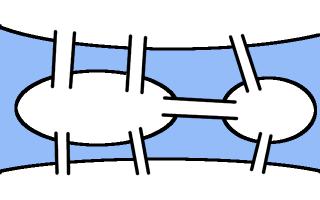

Seven bridges of Königsberg

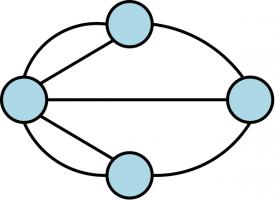

In the 1700s, Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler studied a related problem. The city of

Königsberg had seven bridges, which the residents would try to cross while walking around the

town. However, they were unable to find a route crossing every bridge without repeating one of them.

Diagram showing the bridges in Königsberg. If you have not

seen this puzzle before, you may like to try to find a route crossing them all exactly once before reading on.

In fact, the city dwellers could not find such a route because it is impossible to do so, as

Euler proved in 1735. He first simplified the map of the city, by making the islands into vertices (or nodes)

and the bridges into edges.

This type of diagram has (slightly confusingly) become known as a graph, the study of which is

called graph theory. Euler represented Königsberg in this way as he realised that the shape of the

islands is irrelevant to the problem: representing the problem as a graph gets rid of this useless information

while keeping the important details of how the islands are connected.

Euler next noticed that if a route crossing all the bridges exactly once was possible then whenever

the walker took a bridge onto an island, they must take another bridge off the island. In this way,

the ends of the bridges at each island can be paired off. The only bridge ends that do not need a

pair are those at the start and end of the circuit.

This means that all of the vertices of the graph except two (the first and last in the route) must have an even number of edges connected to them; otherwise there is no route around the graph

travelling along each edge exactly once. In Königsberg, each island is connected to an odd number of bridges. Therefore the route that

the residents were looking for did not exist (a route now exists due to two of the bridges being destroyed during World War II).

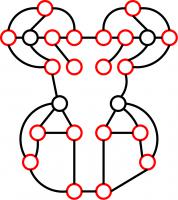

This same idea can be applied to Pac-Man. By ignoring the parts of the maze without pac-dots the pac-graph

can be created, with the paths and the junctions forming the edges and vertices respectively. Once this

is done there will be twenty-four vertices, twenty of which will be connected to an odd number of edges, and so it is impossible to eat

all of the pac-dots without repeating some edges or travelling along parts of the maze with no pac-dots.

This is a start, but it does not give us the shortest route we can take to eat all of the pac-dots: in

order to do this, we are going to have to look at the odd vertices in more detail.

The Chinese postman problem

The task of finding the shortest route covering all the edges of a graph has become known as the

Chinese postman problem as it is faced by postmen—they need to walk along each street to post

letters and want to minimise the time spent walking along roads twice—and it was first studied by

Chinese mathematician Kwan Mei-Ko.

As the seven bridges of Königsberg problem demonstrated, when trying to find a route, Pac-Man

will get stuck at the odd vertices. To prevent this from happening, all the vertices can be made into even

vertices by adding edges to the graph. Adding an edge to the graph corresponds to choosing an edge, or sequence

of edges, for Pac-Man to repeat or including a part of the maze without pac-dots. In order to complete the level

with the shortest distance travelled, Pac-Man wants to add the shortest total length of edges to the graph.

Therefore, in order to find the best route, Pac-Man must look at different ways to pair off the odd vertices and choose

the pairing which will add the least total distance to the graph.

The Chinese postman problem and the Pac-Man problem are slightly different: it is usually assumed

that the postman wants to finish where he started so he can return home. Pac-Man however can finish

the level wherever he likes but his starting point is fixed. Pac-Man may therefore leave one odd

node unpaired but must add an edge to make the starting node odd.

One way to find the required route is to look at all possible ways to pair up the odd vertices. With a low

number of odd vertices this method works fine, but as the number of odd vertices increases, the

method quickly becomes slower.

With four odd vertices, there are three possible pairings. For the Pac-Man problem there will be

over 13 billion (\(1.37\times 10^{10}\)) pairings to check. These pairings can be checked by a

laptop running overnight, but for not too many more vertices this method quickly becomes unfeasible.

With 46 odd nodes there will be more than one pairing per atom in the human body (\(2.53\times 10^{28}\)).

By 110 odd vertices there will be more pairings (\(3.47\times 10^{88}\)) than there are estimated to be atoms in the

universe. Even the greatest supercomputer will be unable to work its way through

all these combinations.

Better algorithms are known for this problem that reduce the amount of work on larger graphs. The number of

pairings to check in the method above increases like the factorial of the number of vertices. Algorithms are

known for which the amount of work to be done increases like a polynomial in the number of vertices. These algorithms

will become unfeasible at a much slower rate but will still be unable to deal with very large graphs.

Solution of the Pac-Man problem

For the Pac-Man problem, the shortest pairing of the odd vertices requires the edges marked in red to be

repeated. Any route which repeats these edges will be optimal. For example, the route in green will be

optimal.

One important element of the Pac-Man gameplay that I have neglected are the ghosts (Blinky, Pinky,

Inky and Clyde), which Pac-Man must avoid. There is a high chance that the ghosts will at some point

block the route shown above and ruin Pac-Man's optimality. However, any route repeating the red edges

will be optimal: at many junctions Pac-Man will have a choice of edges he could continue along. It may

be possible for a quick thinking player to utilise this freedom to avoid the ghosts and complete an optimal

game.

Additionally, the skilled player may choose when to take the edges that include the power pellets,

which allow Pac-Man to reverse the roles and eat the ghosts. Again cleverly timing these may allow

the player to complete an optimal route.

Unfortunately, as soon as the optimal route is completed, Pac-Man moves to the next level and the

player has to do it all over again ad infinitum.

A video

Since writing this piece, I have been playing Pac-Man using

MAME (Multiple Arcade Machine Emulator). Here is one game I played along

with the optimal edges to repeat for reference:

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

@William: You're right. In a number of places I could've turned round a few pixels earlier.

There seems to be no world record for just one Pac-Man level (and I don't have time to get good enough to speed run all 255 levels before it crashes!)

There seems to be no world record for just one Pac-Man level (and I don't have time to get good enough to speed run all 255 levels before it crashes!)

Matthew

This vid was billed as an "optimal" run but around 40 seconds in you eat one "pill" that you don't need to eat. Why don't you just speedrun the first level? This must have been done before. Can you beat the world record?

William

Add a Comment