Blog

2019-04-09

In the latest issue of Chalkdust,

I wrote an article

with Edmund Harriss about the Harriss spiral that appears on the cover of the magazine.

To draw a Harriss spiral, start with a rectangle whose side lengths are in the plastic ratio; that is the ratio \(1:\rho\)

where \(\rho\) is the real solution of the equation \(x^3=x+1\), approximately 1.3247179.

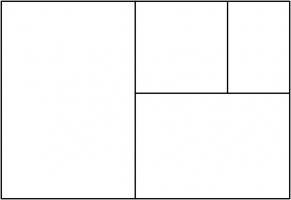

This rectangle can be split into a square and two rectangles similar to the original rectangle. These smaller rectangles can then be split up in the same manner.

Drawing two curves in each square gives the Harriss spiral.

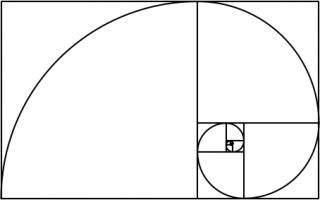

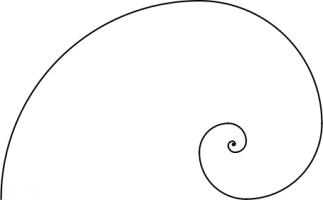

This spiral was inspired by the golden spiral, which is drawn in a rectangle whose side lengths are in the golden ratio of \(1:\phi\),

where \(\phi\) is the positive solution of the equation \(x^2=x+1\) (approximately 1.6180339). This rectangle can be split into a square and one

similar rectangle. Drawing one arc in each square gives a golden spiral.

The golden and Harriss spirals are both drawn in rectangles that can be split into a square and one or two similar rectangles.

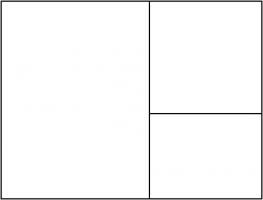

Continuing the pattern of these arrangements suggests the following rectangle, split into a square and three similar rectangles:

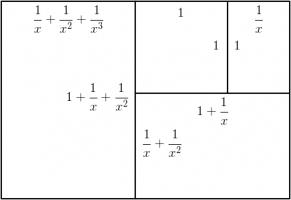

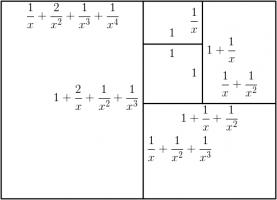

Let the side of the square be 1 unit, and let each rectangle have sides in the ratio \(1:x\). We can then calculate that the lengths of

the sides of each rectangle are as shown in the following diagram.

The side lengths of the large rectangle are \(\frac{1}{x^3}+\frac{1}{x^2}+\frac2x+1\) and \(\frac1{x^2}+\frac1x+1\). We want these to also

be in the ratio \(1:x\). Therefore the following equation must hold:

$$\frac{1}{x^3}+\frac{1}{x^2}+\frac2x+1=x\left(\frac1{x^2}+\frac1x+1\right)$$

Rearranging this gives:

$$x^4-x^2-x-1=0$$

$$(x+1)(x^3-x^2-1)=0$$

This has one positive real solution:

$$x=\frac13\left(

1

+\sqrt[3]{\tfrac12(29-3\sqrt{93})}

+\sqrt[3]{\tfrac12(29+3\sqrt{93})}

\right).$$

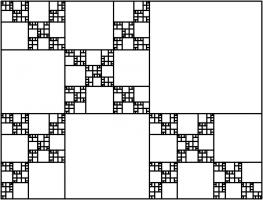

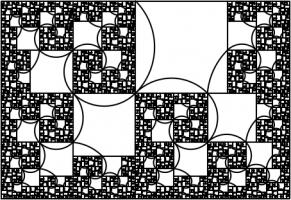

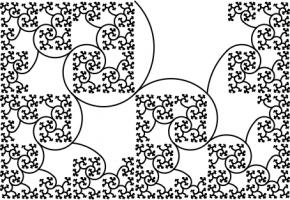

This is equal to 1.4655712... Drawing three arcs in each square allows us to make a spiral from a rectangle with sides in this ratio:

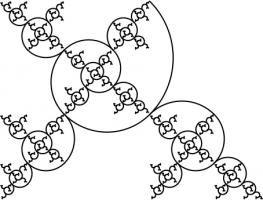

Adding a fourth rectangle leads to the following rectangle.

The side lengths of the largest rectangle are \(1+\frac2x+\frac3{x^2}+\frac1{x^3}+\frac1{x^4}\) and \(1+\frac2x+\frac1{x^2}+\frac1{x^3}\).

Looking for the largest rectangle to also be in the ratio \(1:x\) leads to the equation:

$$1+\frac2x+\frac3{x^2}+\frac1{x^3}+\frac1{x^4} = x\left(1+\frac2x+\frac1{x^2}+\frac1{x^3}\right)$$

$$x^5+x^4-x^3-2x^2-x-1 = 0$$

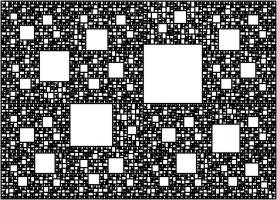

This has one real solution, 1.3910491... Although for this rectangle, it's not obvious which arcs to draw to make a

spiral (or maybe not possible to do it at all). But at least you get a pretty fractal:

We could, of course, continue the pattern by repeatedly adding more rectangles. If we do this, we get the following polynomials

and solutions:

| Number of rectangles | Polynomial | Solution |

| 1 | \(x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.618033988749895 |

| 2 | \(x^3 - x - 1=0\) | 1.324717957244746 |

| 3 | \(x^4 - x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.465571231876768 |

| 4 | \(x^5 + x^4 - x^3 - 2x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.391049107172349 |

| 5 | \(x^6 + x^5 - 2x^3 - 3x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.426608021669601 |

| 6 | \(x^7 + 2x^6 - 2x^4 - 3x^3 - 4x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.4082770325090774 |

| 7 | \(x^8 + 2x^7 + 2x^6 - 2x^5 - 5x^4 - 4x^3 - 5x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.4172584399350432 |

| 8 | \(x^9 + 3x^8 + 2x^7 - 5x^5 - 9x^4 - 5x^3 - 6x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.412713760332943 |

| 9 | \(x^{10} + 3x^9 + 5x^8 - 5x^6 - 9x^5 - 14x^4 - 6x^3 - 7x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.414969877544769 |

The numbers in this table appear to be heading towards around 1.414, or \(\sqrt2\).

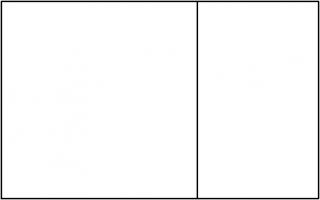

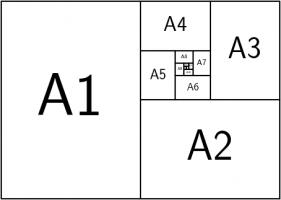

This shouldn't come as too much of a surprise because \(1:\sqrt2\) is the ratio of the sides of A\(n\) paper (for \(n=0,1,2,...\)).

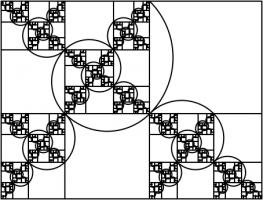

A0 paper can be split up like this:

This is a way of splitting up a \(1:\sqrt{2}\) rectangle into an infinite number of similar rectangles, arranged following the pattern,

so it makes sense that the ratios converge to this.

Other patterns

In this post, we've only looked at splitting up rectangles into squares and similar rectangles following a particular pattern. Thinking about

other arrangements leads to the following question:

Given two real numbers \(a\) and \(b\), when is it possible to split an \(a:b\) rectangle into squares and \(a:b\) rectangles?

If I get anywhere with this question, I'll post it here. Feel free to post your ideas in the comments below.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

2019-05-02

@g0mrb: CORRECTION: There seems to be no way to correct the glaring error in that comment. A senior moment enabled me to reverse the nomenclature for paper sizes. Please read the suffixes as (n+1), (n+2), etc.(anonymous)

I shall remain happy in the knowledge that you have shown graphically how an A(n) sheet, which is 2 x A(n-1) rectangles, is also equal to the infinite series : A(n-1) + A(n-2) + A(n-3) + A(n-4) + ... Thank-you, and best wishes for your search for the answer to your question.

g0mrb

Add a Comment

2018-12-08

Just like last year and the year before, TD and I spent some time in November this year designing a Chalkdust puzzle Christmas card.

The card looks boring at first glance, but contains 10 puzzles. By splitting the answers into pairs of digits, then drawing lines between the dots on the cover for each pair of digits (eg if an answer is 201304, draw a line from dot 20 to dot 13 and another line from dot 13 to dot 4), you will reveal a Christmas themed picture. Colouring the region of the card labelled R red or orange will make this picture even nicer.

If you want to try the card yourself, you can download this pdf. Alternatively, you can find the puzzles below and type the answers in the boxes. The answers will be automatically be split into pairs of digits, lines will be drawn between the pairs, and the red region will be coloured...

If you enjoy these puzzles, then you'll almost certainly enjoy this year's puzzle Advent calendar.

| 1. | What is the smallest four digit number whose digits add up to 6? | Answer |

| 2. | What is the length of the hypotenuse of a right angled triangle whose two shorter sides have lengths 152,560 and 114,420? | Answer |

| 3. | What is the lowest common multiple of 1346 and 196? | Answer |

| 4. | What is the sum of all the odd numbers between 0 and 698? | Answer |

| 5. | How many numbers are there between 100 and 10,000 that contain no 0, 1, 2, or 3? | Answer |

| 6. | How many factors (including 1 and the number itself) does the number \(2^{13}\times3^{19}\times5^9\times7^{39}\) have? | Answer |

| 7. | In a book with pages numbered from 1 to 16,020,308, what do the two page numbers on the centre spread add up to? | Answer |

| 8. | You think of a number, then make a second number by removing one of its digits. The sum of these two numbers is 18,745,225. What was your first number? | Answer |

| 9. | What is the largest number that cannot be written as \(13a+119b\), where \(a\) and \(b\) are positive integers or 0? | Answer |

| 10. | You start at the point (0,0) and are allowed to move one unit up or one unit right. How many different paths can you take to get to the point (7,6)? | Answer |

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

@Carmel: It's not meant to check your answers. It only shows up red if the number you enter cannot be split into valid pairs (eg the number has an odd number of digits or one of the pairs of digits is greater than 20).

Matthew

Great puzzle problems! Hint on #9: try starting with an analogous problem using smaller numbers (e.g. 3a + 10b). This helped me to see what I had to do more generally.

Noah

Add a Comment

2017-12-18

Just like last year, TD and I spent some time in November this year designing a puzzle Christmas card for Chalkdust.

The card looks boring at first glance, but contains 10 puzzles. Converting the answers to base 3, writing them in the boxes on the front, then colouring the 1s black and 2s orange will reveal a Christmassy picture.

If you want to try the card yourself, you can download this pdf. Alternatively, you can find the puzzles below and type the answers in the boxes. The answers will be automatically converted to base 3 and coloured...

| # | Answer (base 10) | Answer (base 3) | ||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

- In a book with 116 pages, what do the page numbers of the middle two pages add up to?

- What is the largest number that cannot be written in the form \(14n+29m\), where \(n\) and \(m\) are non-negative integers?

- How many factors does the number \(2^6\times3^{12}\times5^2\) have?

- How many squares (of any size) are there in a \(15\times14\) grid of squares?

- You take a number and make a second number by removing the units digit. The sum of these two numbers is 1103. What was your first number?

- What is the only three-digit number that is equal to a square number multiplied by the reverse of the same square number? (The reverse cannot start with 0.)

- What is the largest three-digit number that is equal to a number multiplied by the reverse of the same number? (The reverse cannot start with 0.)

- What is the mean of the answers to questions 6, 7 and 8?

- How many numbers are there between 0 and 100,000 that do not contain the digits 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6?

- What is the lowest common multiple of 52 and 1066?

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

@Jose: There is a mistake in your answer: 243 (0100000) is the number of numbers between 10,000 and 100,000 that do not contain the digits 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6.

Matthew

Thanks for the puzzle!

Is it possible that the question 9 is no correct?

I get a penguin with perfect simetrie except at answer 9 : 0100000 that breaks the simetry.

Is it correct or a mistake in my answer?

Thx

Is it possible that the question 9 is no correct?

I get a penguin with perfect simetrie except at answer 9 : 0100000 that breaks the simetry.

Is it correct or a mistake in my answer?

Thx

Jose

@C: look up something called Frobenius numbers. This problem's equivalent to finding the Frobenius number for 14 and 29.

Lewis

Add a Comment

2017-11-14

A few weeks ago, I took the copy of MENACE that I built to Manchester Science Festival, where it played around 300 games against the public while learning to play Noughts and Crosses. The group of us operating MENACE for the weekend included Matt Parker, who made two videos about it. Special thanks go to Matt, plus

Katie Steckles,

Alison Clarke,

Andrew Taylor,

Ashley Frankland,

David Williams,

Paul Taylor,

Sam Headleand,

Trent Burton, and

Zoe Griffiths for helping to operate MENACE for the weekend.

As my original post about MENACE explains in more detail, MENACE is a machine built from 304 matchboxes that learns to play Noughts and Crosses. Each box displays a possible position that the machine can face and contains coloured beads that correspond to the moves it could make. At the end of each game, beads are added or removed depending on the outcome to teach MENACE to play better.

Saturday

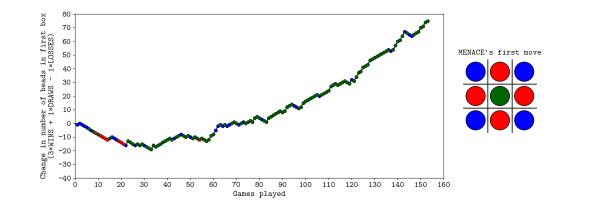

On Saturday, MENACE was set up with 8 beads of each colour in the first move box; 3 of each colour in the second move boxes; 2 of each colour in third move boxes; and 1 of each colour in the fourth move boxes. I had only included one copy of moves that are the same due to symmetry.

The plot below shows the number of beads in MENACE's first box as the day progressed.

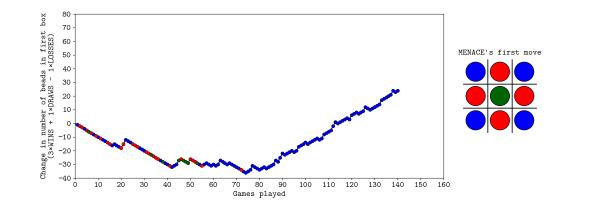

Originally, we were planning to let MENACE learn over the course of both days, but it learned more quickly than we had expected on Saturday, so we reset is on Sunday, but set it up slightly differently. On Sunday, MENACE was set up with 4 beads of each colour in the first move box; 3 of each colour in the second move boxes; 2 of each colour in third move boxes; and 1 of each colour in the fourth move boxes. This time, we left all the beads in the boxes and didn't remove any due to symmetry.

The plot below shows the number of beads in MENACE's first box as the day progressed.

You can download the full set of data that we collected over the weekend here. This includes the first two moves and outcomes of all the games over the two days, plus the number of beads in each box at the end of each day. If you do something interesting (or non-interesting) with the data, let me know!

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

WRT the comment 2017-11-17, and exactly one year later, I had the same thing happen whilst running MENACE in a 'Resign' loop for a few hours, unattended. When I returned, the orange overlay had appeared, making the screen quite difficult to read on an iPad.

g0mrb

On the JavaScript version, MENACE2 (a second version of MENACE which learns in the same way, to play against the original) keeps setting the 6th move as NaN, meaning it cannot function. Is there a fix for this?

Lambert

what would happen if you loaded the boxes slightly differently. if you started with one bead corresponding to each move in each box. if the bead caused the machine to lose you remove only that bead. if the game draws you leave the bead in play if the bead causes a win you put an extra bead in each of the boxes that led to the win. if the box becomes empty you remove the bead that lead to that result from the box before

Ian

Hi, I was playing with MENACE, and after a while the page redrew with a Dragon Curves design over the top. MENACE was still working alright but it was difficult to see what I was doing due to the overlay. I did a screen capture of it if you want to see it.

Russ

Add a Comment

2017-03-08

This post appeared in issue 05 of Chalkdust. I strongly

recommend reading the rest of Chalkdust.

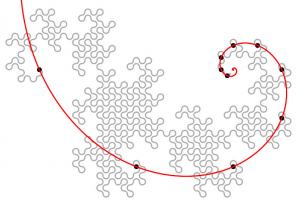

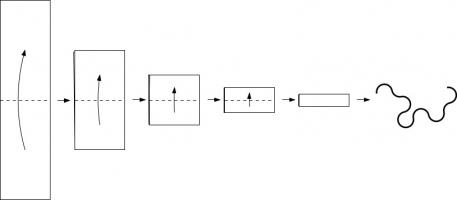

Take a long strip of paper. Fold it in half in the same direction a few times. Unfold it and look at the shape the edge of the paper

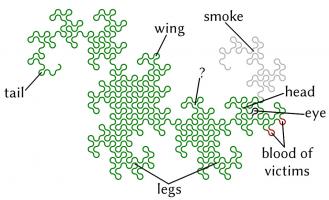

makes. If you folded the paper \(n\) times, then the edge will make an order \(n\) dragon curve, so called because it faintly resembles a

dragon. Each of the curves shown on the cover of issue 05 of Chalkdust is an order 10 dragon

curve.

Top: Folding a strip of paper in half four times leads to an order four dragon curve (after rounding the corners). Bottom: A level 10 dragon curve resembling a dragon.

The dragon curves on the cover show that it is possible to tile the entire plane with copies of dragon curves of the same order. If any

readers are looking for an excellent way to tile a bathroom, I recommend getting some dragon curve-shaped tiles made.

An order \(n\) dragon curve can be made by joining two order \(n-1\) dragon curves with a 90° angle between their tails. Therefore, by

taking the cover's tiling of the plane with order 10 dragon curves, we may join them into pairs to get a tiling with order 11 dragon

curves. We could repeat this to get tilings with order 12, 13, and so on... If we were to repeat this ad infinitum we would arrive

at the conclusion that an order \(\infty\) dragon curve will cover the entire plane without crossing itself. In other words, an order

\(\infty\) dragon curve is a space-filling curve.

Like so many other interesting bits of recreational maths, dragon curves were popularised by Martin Gardner in one of his Mathematical Games columns in Scientific

American. In this column, it was noted that the endpoints of dragon curves of different orders (all starting at the same point) lie on

a logarithmic spiral. This can be seen in the diagram below.

Although many of their properties have been known for a long time and are well studied, dragon curves continue to appear in new and

interesting places. At last year's Maths Jam conference, Paul Taylor gave a talk about my favourite surprise occurrence of

a dragon.

Normally when we write numbers, we write them in base ten, with the digits in the number representing (from right to left) ones, tens,

hundreds, thousands, etc. Many readers will be familiar with binary numbers (base two), where the powers of two are used in the place of

powers of ten, so the digits represent ones, twos, fours, eights, etc.

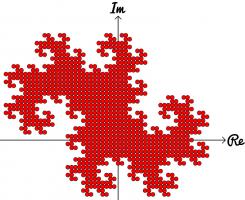

In his talk, Paul suggested looking at numbers in base -1+i (where i is the square root of -1; you can find more adventures of i here) using the digits 0 and 1. From right to left, the columns of numbers in this

base have values 1, -1+i, -2i, 2+2i, -4, etc. The first 11 numbers in this base are shown below.

| Number in base -1+i | Complex number |

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 |

| 10 | -1+i |

| 11 | (-1+i)+(1)=i |

| 100 | -2i |

| 101 | (-2i)+(1)=1-2i |

| 110 | (-2i)+(-1+i)=-1-i |

| 111 | (-2i)+(-1+i)+(1)=-i |

| 1000 | 2+2i |

| 1001 | (2+2i)+(1)=3+2i |

| 1010 | (2+2i)+(-1+i)=1+3i |

Complex numbers are often drawn on an Argand diagram: the real part of the number is plotted on the horizontal axis and the imaginary part

on the vertical axis. The diagram to the left shows the numbers of ten digits or less in base -1+i on an Argand diagram. The points form

an order 10 dragon curve! In fact, plotting numbers of \(n\) digits or less will draw an order \(n\) dragon curve.

Brilliantly, we may now use known properties of dragon curves to discover properties of base -1+i. A level \(\infty\) dragon curve covers

the entire plane without intersecting itself: therefore every Gaussian integer (a number of the form \(a+\text{i} b\) where \(a\) and

\(b\) are integers) has a unique representation in base -1+i. The endpoints of dragon curves lie on a logarithmic spiral: therefore

numbers of the form \((-1+\text{i})^n\), where \(n\) is an integer, lie on a logarithmic spiral in the complex plane.

If you'd like to play with some dragon curves, you can download the Python code used

to make the pictures here.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment